This blog post is Jeong-Nam Kim’s follow up post to last week’s entry, “An Innovative Organization and Its Many Oracles.”

Promotive-Consequence of ECBs: Strategic Value of ECBs in Innovation Management

While earlier findings have provided evidence about the importance of ECBs in risk management, ECBs also generate strategic value by making the organization more innovative and progressive. Scouting, especially, is a key vehicle for an organization to identify and seize strategic opportunities, such as new business ideas and niche markets.

While earlier findings have provided evidence about the importance of ECBs in risk management, ECBs also generate strategic value by making the organization more innovative and progressive. Scouting, especially, is a key vehicle for an organization to identify and seize strategic opportunities, such as new business ideas and niche markets.

As noted earlier, employee scouting produces large amount of information that may be crucial for management and business units. The most critical value of scouting is in the information quality it generates. To a certain extent all employees are all trained experts in their respective area of corporate business function or process. A major portion of their job activities is to initiate and maintain informal and formal communicative interactions with consumers, government regulatory agencies, partners, and suppliers. These key publics and stakeholders are the main sources of begetting new opportunities (e.g., new product ideas, creation of niche market) and impending threats (e.g., hostile regulation, market failing). Therefore, each and every employee is in the frontline of potential information mines, detecting what is going in and around their organization and anticipating future needs.

Here comes the value of employees’ voluntary scouting. Employees may become non-designated informational agents using their personal and impersonal networks. They may be an effective informal mechanism to identify and communicate emerging trends and threats on- and off-duty. Most importantly, employee scouting transforms mere environmental signals (data) to meaningful management intelligence (information) because employees deploy their expertise and experiences in detecting the signals and further digest and transform data into critical business information through their cognitive processing. Employees, in the process of scouting, make critical judgments of the relevance of trends and signals and add their interpretation in what they convey to their organization and business. Therefore, the public relations function and management overall should recognize the complementary role of employee scouting. Our studies have found that good (communication) management will promote good organization-employee relationship and the quality of relationship strongly influences employee scouting.

Innovation is expected to come from systematic investment toward research and development. Yet, it often comes through serendipitous and informal ways. In fact, innovation opportunities arise frequently when employees question routine procedures, programmed services, and repeated production activities. When individual employees take innovative ideas and effectuate them in their workplace, this is called intrapreneurship.

The latest study by Soo Park et al. found that three managerial factors have a causal influence to employees’ perceived relationship with their working organization, and this mediates intrepreneurship and scouting. Intrapreneurship is “employee initiative from below in the organization to undertake something new; an innovation which is created by subordinates without being asked, expected, or perhaps even given permission by higher management to do so” (Vesper, 1984, p. 295). Intrapreneurial employees start new ventures within the company. This requires the hosting organization to motivate and facilitate an entrepreneurial mindset for their employees in the workplaces. Employees with high intrapreneurship are likely to seek out and circulate innovative ideas within the organization. In other words, intrepreneurial employees are likely to engage in scouting in their work processes.

Some New Evidence

Park et al.’s study is based on 528 participants working in various types of businesses and size of companies.[i]Using the dataset, I analyzed and reported below the differences between the top-performing companies and low-performing companies in terms of management approach, relationship quality, and intrepreneurship and employee scouting.

To prepare for this comparison, I used five measures to evaluate corporate performance (5 point Likert-type scale) and created a composite and further segment into the top 20% percentile (top-performance companies) and bottom 30% percentile (bottom-performance companies).[ii]

The measures are:

- This organization is considered one of the best in its industry.

- Employees of other organizations would be proud to work in this organization.

- This organization has a good reputation.

- This organization is looked upon as a prestigious place to work for.

- People in my community think highly of this organization.

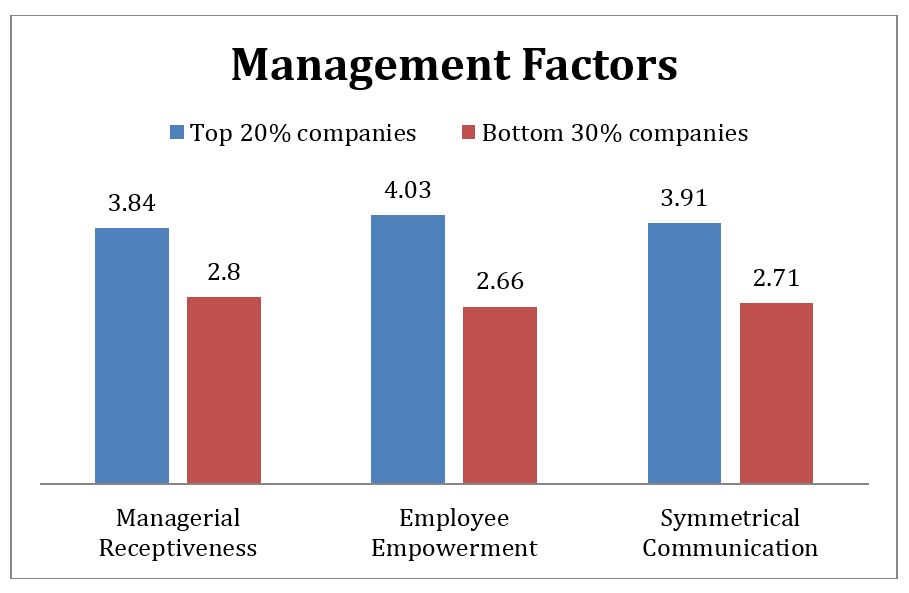

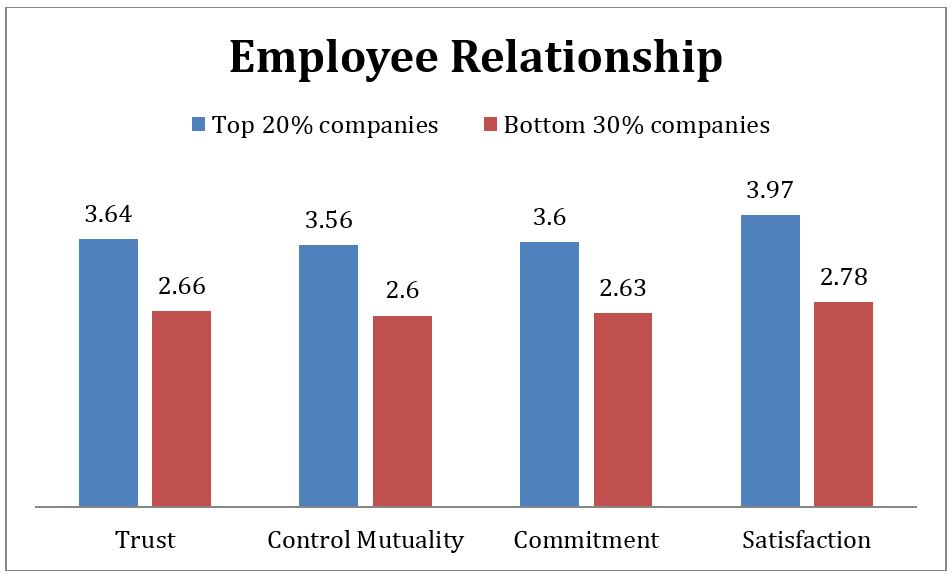

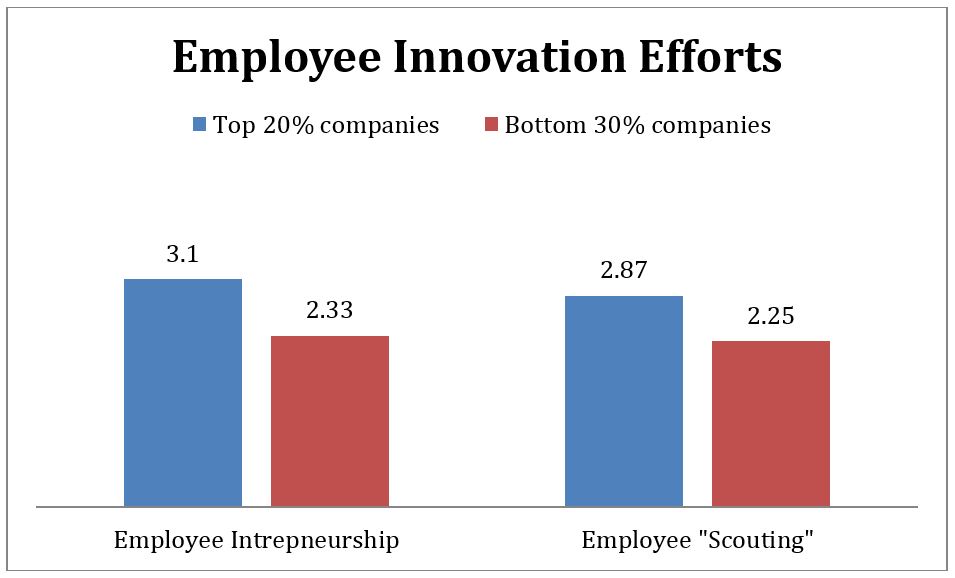

The findings are summarized below Figures with mean scores.

All the comparison tests yielded statistically significant results at p < .001. In summary, it was found that effective, top-performing companies tend to solicit and are receptive to new ideas from employees, empowering employees in governance, and take into account employees’ interests in management decisions and policy-making. Following this, the top-performing companies cultivate higher trust and shared controls between the company and its employees, and earn more commitment from employees with higher satisfaction. Finally, those top-performing companies develop higher employee intrepreneurship and higher voluntary scouting among employees.

Matrix Structure and Grassroots Structure: A Complementary Information Trafficking

In the good corporate management structure, there should be a functional unit that formally gathers and delivers business intelligence to decision-makers and responsible managerial units. The behavioral, strategic management paradigm (aka. the Excellence theory or the general theory of public relations management) found and prescribed that public relations play such a functional role in making its hosting organization more effective and ethical (L. Grunig, J. Grunig, and Dozier, 2002; J. Grunig & Kim, 2011). For instance, the behavioral, strategic management theorists suggest a matrix structure of communication managers in which the public relations head plays the role of a chief information officer (CIO) who links and coordinates information from all managerial units. This CIO is like an oracle who consults people when they get inspiration from the gods for the future.

About two-thirds of strategic intelligence is reaped from informal sources and a variety of human networks (Stoffels, 1994). That said, the role of each employee as an information agent will be a better way of combing through key business information and opportunities and threats from organizational environments. In fact, motivating individual employees as scouts will be an informal but complementary communication arrangement to a matrix structure. Though not in a formal configuration, there are strategies to make employees more motivated and to facilitate information trafficking within and across functional units and teams by awarding incentives and design communication procedures and information-pooling software. I refer, then, to a grassroots structure of information trafficking that can be complementary to the matrix arrangement of formal communication managers. Indeed, even the most ideally organized strategic public relations management department would not capture all the possible intelligence alone. Hence, the complementary role of a matrix structure and grassroots structure is encouraged to make the functions more interdependent.

Meanwhile, what a formal, strategic PR manager should do is 1) to create employee motivation for intrapreneurship and scouting through relationship-cultivation strategies, 2) to build a communication structure and information-pooling procedure (i.e., incentives, software for pooling scouted information into an internal database) which will result in organization-unique “big data,” and regularly mine this data to generate management and leadership insights, and, 3) to distinguish strategic signals from “almost strategic” ones and generate and deliver business insights to organizational leaders. In this vein, a formal and informal environmental scanning function of public relations emerges as an essential tool for strategic management. To do so, public relations should be more behaviorally and strategically managed so that it may build relationships with employees and lay the groundwork for information flow, and cheer-lead the more active information behaviors of individual members of organization.

Coda: Oracles within Us

Lots of consulting firms and futurist researchers reap huge financial gains from anxious corporate leaders who want to know the future. The so-called prediction market has emerged as its own industry, as a meta business – a business about business. Corporate leaders and strategic managers are willing to pay huge amount of corporate resources even for a glimpse of the future they will face. They look for an oracle from outside.

If you want to know and plan the future, don’t go too far. It’s better to look inside and listen to your employees, not the futurist. According to our research, these leaders and strategic managers already have a good oracle, actually, many oracles at home. The future is hinted upon in a more mundane and earthly way by many lay employees.

If leaders and management turn to employees and their ECBs, they will get the ideas and information they need. Every employee is an oracle, more or less. What most amazing thing is that your employees are not only oracles who have precognition of the future but also shape the future themselves.

They are like self-fulfilling prophets – as employees are motivated, they are eager to fulfill their predictions and become intrapreneurs who capture and materialize emerging signals and capitalize new ideas becomes reality.

Got oracles?

References

- Grunig, L. A., Grunig, J. E., & Dozier, D. M. (2002). Excellent public relations and effective organizations: A study of communication management in three countries. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Grunig, J. E., & Kim, J.-N. (2011). Actions speak louder than words: How a strategic management approach to public relations can shape a company’s brand and reputation through relationships. Insight Train, 1(1), 36-51.

- Kim, J.-N. (2012) (guest editor). Strategic values of relationships and the communicative actions of publics and stakeholders. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6, 1.

- Kim, J.-N., & Rhee Y. (2011). Strategic thinking about employee communication behavior (ECB) in Public Relations: Testing the Models of Megaphoning and Scouting Effects in Korea. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23(3), 243-268.

- Park, S. H., Kim, J.-N., & Krishna, A. (in press). Bottom-up building of an innovative organization: Motivating employee intrepreneurship and scouting and their strategic vales. Management Communication Quarterly.

- Stoffels, J. D. (1994). Strategic issues management: A comprehensive guide to environmental scanning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Vesper, K. H. (1984). Three faces of corporate entrepreneurship. In J. A. Hornaday et al. (Eds.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 294-320). Wellesley, MA: Babson College.

[iv] Detailed information about the sample profiles and data can be found in upcoming Park et al.’s MCQ article or available by request. In brief, using paid online participant panel, each participant is most likely to represent different companies and thus it is assumed that each participant’s evaluation of their working organization as representing for 528 different companies. However, we acknowledge that it is possible that some participants might work for the same companies and thus response independence may not be perfectly assumed.

[v] The resulting subsamples of top and bottom percentiles are not clear cut although it was intended for 25% each to top and bottom because of same scores. So, the nearest cutting point was selected.

Jeong-Nam Kim is an associate professor in the Brian Lamb School of Communication at Purdue University. The key findings in the essay are original while the data and key factors are drawn from the study that will be published in Management Communication Quarterly with Soo Hyun Park and Arunima Krishna.