This blog post appears courtesy of the Society for New Communications Research of The Conference Board. For the full study, please visit here.

Public attention about online misinformation has been largely focused on the business practices of the social platforms—especially Facebook and Google. Yes, the two net giants are the 600-pound gorillas of fake news, but they serve as an accelerator to a wider ecosystem of sites designed to game advertising technology.

AdTech, and the money it can bring to popular pages serving ads, sits at the center of the issue—making big brand marketers reluctant players in this controversial space.

A new study by the Society for New Communications Research of The Conference Board (SNCR) shows that while marketers are now aware of their inadvertent participation, they are ambivalent about what ought to change—and are reluctant to alter their own business practices.

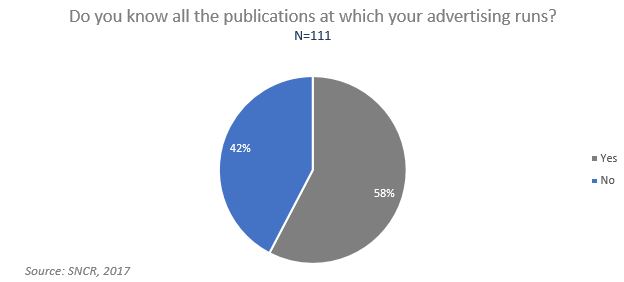

Almost half of marketers surveyed have so little control over their ad programs that they do not know where their ads are running.

When asked who should take the lead in solving the problem, the highest proportion of respondents say publishers and the social media platforms.

The study, conducted late summer through fall, surveyed marketers to gauge their awareness of the issue and what action, if any, they are willing to take. The survey was framed around “fake news,” defined as “content that lacks trusted sources and often uses sensational headlines to encourage the consumption and spread of unverified or false information. It can be left- or right- leaning. Such content typically masquerades as legitimate news reports.”

For marketers, the question was less about the impact of fake news on society and more about the impact associating with unsavory content can have on their brands.

Follow the Money

More and more marketers are aware of the problem: 69 percent say they have personally seen “fake news” in digital channels and 75 percent say they have seen it on social channels in the month they took the survey, with 85.8 percent citing editorial content as the source and nearly 59.3 percent citing native advertising or paid content marketing as the source. It is notable that while Facebook, Twitter and the search engines were the platforms most cited as housing fake news, Instagram, LinkedIn and Snap were the lowest.

Of those who saw fake news, 42 percent say they were aware of ads adjacent to the content. And nearly 70 percent of those marketers say they had a negative or very negative impression of the advertiser in those positions. Overall, 95 percent of marketers say that association with fake news could erode consumer trust in the brand.

Ad dollars—an estimated $550 billion worldwide in 2017, according to ad buying firm GroupM—fuel the entire ecosystem, powering both the relentless growth of Facebook and Google and the thousands of sites that have popped up over the past several years publishing suspect content. Digital ad budgets alone are expected to reach $335 billion worldwide by 2020, according to GroupM, a unit of WPP.

And, two-thirds of the world’s digital display advertising will be programmatic by 2019, up from 59 percent in 2017, according to Zenith’s Programmatic Marketing Forecasts. The United States is the largest programmatic market, valued at $32.6 billion in 2017. Google and Facebook are expected to account for just over 63 percent of the total (programmatic and direct) U.S. digital ad market, with Google accounting for $35 billion total digital ad dollars and Facebook taking more than $17 billion. According to GroupM, Google and Facebook will account for 84 percent of all digital media money for 2017.

Programmatic is not confined to digital ads. In Zenith’s forecasts, it estimates that $5.6 billion will be spent programmatically across television, radio, cinema and even outdoor in the United States this year, 6.0 percent of total ad spend for these media. By 2019 the number is expected to rise to $13.0 billion, 13.6 percent of the total.

How Adtech Works

Before the commercialization of publishing on the internet, advertising was a much cozier proposition. Marketers would indicate their desired audience, create their message, and pick publications, television and radio stations who said they could reach that audience with their message.

The promise of digital advertising has long been personalization, the ability to reach specific individuals who met an advertiser’s criteria regardless of where they are online. And thus, the advent of “programmatic adtech,” the ability for ads to tag and follow people throughout the internet. This allows marketers to buy access to audiences that fit their profile across multiple sites. The key is the audience demographics, not the site’s editorial value or context. Programmatic advertising disaggregates digital audiences from digital publishers.

The result is a massive new form of direct marketing—pumping billions of dollars through the system—that uses algorithms to match marketers with audiences. And they do it at a price with which premium publications cannot compete.

But with adtech comes a tangle of technology, agencies, ad networks, exchanges and platforms that are impenetrable to even the most sophisticated observers. Marketers get their audiences—but often have no idea from where—leaving them vulnerable for their ads to appear next to pornography, fake news, pirated content, videos espousing extreme views, and even fraudulent traffic driven by bots. (YouTube is a particularly vulnerable platform.)

And with the confusion comes an unintended business model. A clever new class of digital publishers who monetize the lack of transparency. Their innovation: create popular pages by fueling outrage with fictional news stories, build scale on the social platforms, and make money by running programmatic ads. The system was famously exploited by teenagers in Macedonia who built at least 140 fake pro-Trump sites during the election and made money through Google AdSense and Facebook.

Thus, we have seen the explosion of fake news, and a recent rise in concern by marketers, largely driven by fears about “brand safety”—the perception that their brand can be harmed by proximity to inappropriate content.

Concern. But…

According to the SNCR study, more than 80 percent of marketers are somewhat concerned or extremely concerned that their ads might appear adjacent to fake news. Eighty-two percent believe their brands will be harmed by the affiliation.

So, what’s a marketer to do?

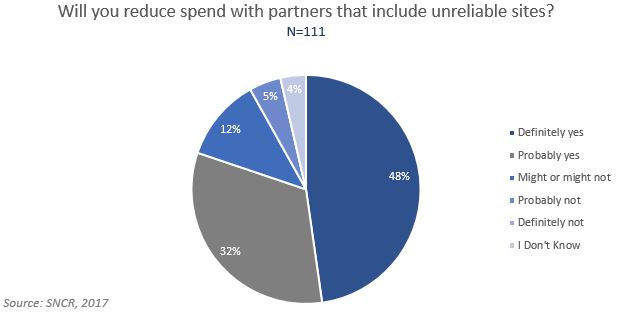

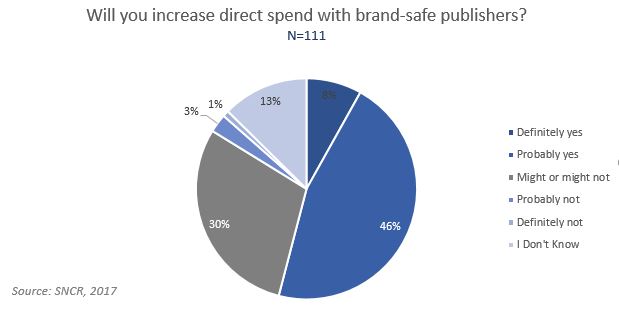

Whereas nearly 80 percent of respondents say they would “probably” or “definitely” reduce their level of spend with partners that include unreliable sites, they are ambivalent about joining “private markets,” closed exchanges that include only known and vetted sites. They are split on returning to direct relationships with brand-safe publishers, with 46 percent saying they “probably” would return to premium publishers and another 30 percent saying they were unsure.

It is noteworthy, however, that US programmatic digital ad spending through private marketplaces will reach $9.23 billion, almost as much as the $9.61 billion expected to be spent with open exchanges, according to eMarketer. Still, only 20 percent of marketers in the study say they will leave open exchanges.

In a separate study conducted at roughly the same time by the CMO Council and Dow Jones, marketers put the responsibility on media buying firms to ensure appropriate ad placement. Half of marketers in this study say they are preparing guidelines for their agencies. This result differs from the SNCR study.

More broadly, there is no consensus as to whether the problem can be solved at all. A recent survey of “internet and technology experts” conducted by the Pew Research Center and Elon University found this community split down the middle.

According to the Pew survey, those who do not think things will improve say people will always use technology for their own, selfish purposes; bad actors with bad motives will exploit technology in unexpected ways.

Slowly, The Industry Engages

Despite the fatalism of the Pew survey result, many in the industry are starting to take on the issue. Earlier this year, Proctor & Gamble (P&G), the world’s largest advertiser, cut $140 million from its quarterly ad spend, citing concerns over brand safety. Since then P&G has insisted that all digital programs be accredited by the Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG) to fight fraudulent metrics, a closely related issue tied to programmatic advertising. There are currently about 170 companies undergoing TAG review for accreditation. An estimated $6.5 billion in ad spending is expected to be wasted this year due to fraud, according to a report released in May by White Ops and the Association of National Advertisers.

Some adtech companies are starting to view transparency as a market opportunity. TrustX, for example, is collaborating with publishing trade organization Digital Context Next to bring premium publishers together as a kind of programmatic advertising co-op. They have 35 publishers committed, and 16 that are actively trading, including Hearst, NBCU, CBS Interactive, The Washington Post, New York magazine, and The Atlantic.

And industry pundits like Doc Searls and Bob Hoffman have been proselytizing the industry to move away from programmatic advertising, both calling for technical, financial and reporting transparency. Searls recently created Customer Commons to spell out terms for consumers to control how their information is used by businesses, websites and apps.

Even regulation is on the table. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators proposed oversight of political ads on the internet, similarly to the way they are monitored on TV. And there is discussion of much tougher regulation that can force the internet giants to be more transparent and give consumers more control over how information about them is used.

Now more than ever, brand building is about establishing trust with customers and prospects. The SNCR study indicates that marketers—those with the most leverage—are acutely aware of the risk but remain divided about how to move things forward. And while the advertising models that built the world’s most valuable brands are exposed, the stakes are even higher for society. Advertising serves a public good when it supports credible content providers. When it fails—when brands forgo their social responsibility—brands, communities, and democratic institutions are all undermined.

Jeff Pundyk is Chief Strategy Officer and Editorial Director of Techonomy. He is also an advisory board member of the Society for New Communications Research of The Conference Board. Follow Jeff on Twitter @Jpundyk.

Jeff Pundyk is Chief Strategy Officer and Editorial Director of Techonomy. He is also an advisory board member of the Society for New Communications Research of The Conference Board. Follow Jeff on Twitter @Jpundyk.