This blog post features an IPR Signature Study. The white paper, “Protecting Online Image in a Digital Age: How Trademark Issues Affect PR Practice” was released in the Research Journal of IPR, Volume III, Issue I. The full paper is available here.

“Image is everything” was the slogan of a 1990s TV commercial by Canon featuring Andre Agassi. This slogan ironically became part of Cannon’s and Agassi’s image in the 1990s, and underscores the power of words and symbols. However, with image comes responsibilities and problems. For PR practitioners the control of clients’ image is a source of pride and frustration. It is, in many respects, one of the core functions of public relations. This responsibility of image management has become more complex in the digital age where organizations’ images are frequently stolen, misused, maligned, and ridiculed online. Practitioners (and legal departments) work hard to maintain control, but in many cases there is never a final resolution because there are always more image issues on the horizon. This situation begs the question, can practitioners ever control image completely?

As any seasoned practitioner will tell you the answer is probably not. However, one of the strongest tools in controlling online image is the law, particularly trademark law. Unlike other types of laws that affect PR practice, trademark law is actually directly affected by how practitioners represent their clients’ image. Strategic communication and deliberate use of image actually provides organizations greater legal protection under trademark law. For instance, the more famous a trademark is the greater protection it receives. In fact, under federal trademark law, sometimes referred to as the Lanham Act, a famous trademark not only can sue unauthorized users for infringement, but can also sue them for dilution, which is a type of lawsuit that directly combats harm to well-known images. Similarly, the more a trademark is used the greater strength it has. Descriptive trademarks, for instance, only receive trademark protection once they receive a secondary meaning. This secondary meaning can only be established by continually promoting a trademark to the point that it becomes associated with a specific organization. Conversely, not using a trademark risks not only infringement, but the loss of the trademark itself. Continual deliberate communication is the most important and most effective way of legally protecting an organization’s online image.

But…what about parody? With the advent of social media parody accounts have proliferated. Successful parody accounts sometimes have more followers than the “real” or “official” accounts of those parodied. Legally there are measures to stop this, but the threshold is often so high that no plaintiff can achieve success. Part of the reason for this is the value that parody has under the U.S. Constitution. Parodies of famous people are viewed by courts as the price of celebrity. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court held that for a public figure or official to win a case of emotional distress based on parody the figure must show the creator of the parody acted with actual malice, a very difficult legal standard (Hustler Magazine Inc. v. Falwell, 1988).

Parody is also a factor that weighs in favor of a trademark infringer. When a trademark is infringed the court may find that the infringement is less because it is a parody. In trademark law parody seems to have gotten more strength in the last twenty years in light of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc. (1994). The trend in trademark parody is that courts tend to look at economic confusion as a the most important, if not the sole, determining factor for infringement. What has resulted in some lawsuits where other organizations’ use of famous logos or names were viewed as parody and therefore not considered infringement (Louis Vuitton Malletier v. My Other Bag, Inc., 2016; Radiance Foundation Inc. v. NAACP, 2015).

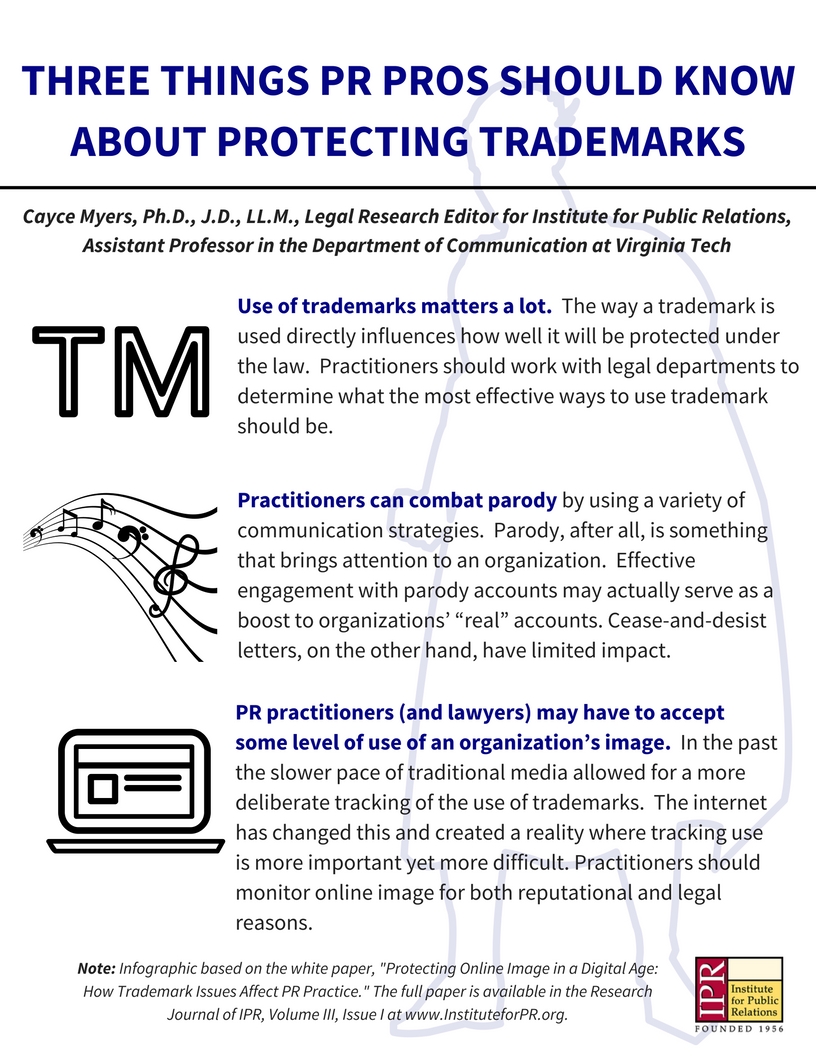

Given the complexity of online image management in the twenty-first century PR practitioners should know three things:

- PR practitioners’ use of trademarks matter—a lot. As mentioned earlier the way a trademark is used directly influences how well it will be protected under the law. Practitioners should work with legal departments to determine what the most effective ways to use trademark should be. Too often the branding guidelines of an organization are viewed as an obstacle to creative content. Instead practitioners should use the tenets of trademark law to develop effective strategies to maintain and promote an organization’s image. Promotion and fame are boosts to any trademark both commercially and legally. Practitioners are in a unique position to provide key services needed in this area.

- PR practitioners need to figure out other ways to combat negative attention based on parody. As recent trends show, parody on social media is both ubiquitous and gaining strength under the law. In the past attorney cease-and-desist letters were a major way parodies were stopped. This approach has limited impact, especially given that courts now protect parody at a greater rate. Practitioners are in the best position to combat parody by using a variety of communication strategies. Parody, after all, is something that brings attention to an organization. Effective engagement with parody accounts may actually serve as a boost to organizations’ “real” accounts.

- PR practitioners (and lawyers) may have to accept some level of use of an organization’s image. In the past the slower pace of traditional media allowed for a more deliberate tracking of the use of trademarks. The internet has changed this and created a reality where tracking use is more important yet more difficult. Practitioners should continue to monitor online image for both reputational and legal reasons. However, with the rise of parody sites, greater access to organizational images, and the proliferation of social media platforms there is going to be some type of unauthorized use of an organization’s image. Sometimes these can be stopped, but as legal trends show sometimes they cannot. This reality is perhaps the strongest argument for organizations to have a more thoughtful, strategic, and fully staffed public relations team.

The use of trademarks and rise of parodies shows that now more than ever communication problems lend themselves to communication solutions. While litigation is always a necessary component of maintaining an organization’s image and property, public relations has a significant contribution to make. Practitioners are in many ways the best equipped group to recognize these ongoing problems. Knowing the limits of how the law can protect their clients’ image better positions them to make more strategic, and ultimately more beneficial, solutions for their clients’ problems.

Cayce Myers, Ph.D., LL.M. J.D., serves as research editor for IPR in the area of public relations law. He is an assistant professor at Virginia Tech’s department of communication where he teaches public relations. Follow him on Twitter @caycemyers.

Cayce Myers, Ph.D., LL.M. J.D., serves as research editor for IPR in the area of public relations law. He is an assistant professor at Virginia Tech’s department of communication where he teaches public relations. Follow him on Twitter @caycemyers.

References

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510 U.S. 569 (1994).

Hustler Magazine Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988).

Louis Vuitton Malletier v. My Other Bag, Inc., No. 14-CV-3419 , 2016 WL 70026 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2016).

Radiance Foundation Inc. v. NAACP, 786 F.3d 316 (4th Cir. 2015).