The Behavioral Communications research program is sponsored by ExxonMobil, Public Affairs Council, Mosaic, and Gagen MacDonald.

This is the third blog in a three-part series that launches IPR’s Behavioral Communications research program. Each week focused on a different aspect of Behavioral Communications.

PDF: Part Three: What The Vulcan Mind Meld Can Teach Communicators

Back to our roots: the Science Beneath the Art of CommunicationsTM

While public relations once called itself an applied social science, it now risks being left behind as anachronistic. After decades of fine tuning its execution in media relations, mapping influencers, developing detailed plans to segment and target separate audiences for messaging, PR has not kept pace with scientific discoveries in behavioral economics, neuroscience and narrative theory. But now, by connecting three historic accidents and discoveries, we can revitalize this social science to bring far more effectiveness and scientific underpinning to the art of narrative that lies at the very core of successful public relations and all communications. This is a three-part series revealing three compelling lessons communicators can learn from three historic scientific events.

Part Three: What The Vulcan Mind Meld Can Teach Communicators

The third discovery in our three-part series involved a sort of voyeurism in a neuroscience lab at the University of Parma, Italy in the early 1990’s. There, Giacomo Rizzolatti and his team of scientists were localizing and tracking the firing of specific neurons in macaque monkeys. Neurons are transmitters in the brain that fire and trigger every human motor action. Rizzolatti’s team had put probes into the monkeys’ brains to isolate very specific neurons controlling very specific motor actions—in this case grasping a piece of food and bringing it to their mouth. In order to track the firing of neurons, they wired the signals to a speaker which would crackle every time the neurons fired. But as the story goes,[1] one day, as a scientist put a piece of food up to his own mouth, they heard the crackle of neurons firing in the observing monkey. Those minute brain transmitters had a purpose beyond controlling all motor functions. They allow the observer to mirror and feel what the actor is doing. This discovery of so-called “mirror neurons” led scientist V.S. Ramachandran to proclaim this “the greatest discovery in neuroscience since Darwin.” Scientists call these mirror neurons the neuro-biological roots of human empathy, an evolutionary development that allows species with such powers to learn from each other without having to recreate every experience for themselves. For example, if I were to pick up a tall glass of cold water, my brain would activate all the many motor skills necessary for me to balance it without spilling. Yet by merely watching me, your brain would mirror me, activating the very same parts of the brain even though you are not picking up anything.

Curiosity drove scientists to move beyond motor skills to test whether humans also mirror another’s emotions. They do. V.S. Ramachandran says “we used to say, metaphorically, that ‘I can feel another’s pain.’ But now we know that my mirror neurons can literally feel your pain.”[2]

But beyond mirroring simple motor skills, are humans wired to mirror thoughts, emotions and whole narratives as well?

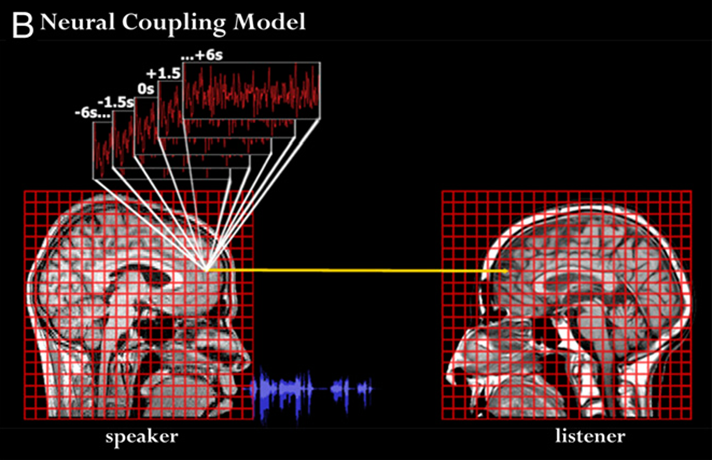

Uri Hasson, assistant professor at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, sought to discover whether humans generate mirror neurons during storytelling. Hasson tracked their brain patterns and found the listener’s brain did indeed mirror the teller, but at a slight delay. Then, as the story evolved, the listener mirrored the storyteller synchronously with no delay. Finally, and here’s the Vulcan “Mind Meld” part—the listener’s brain started accurately mirroring the teller’s brain before the teller got to that part of the story. They were truly on the same wave length. Hasson calls this “neural coupling.” Neural coupling demonstrates the power of narrative to trigger an empathetic simulation in the listener’s brain.

Uri Hasson, assistant professor at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, sought to discover whether humans generate mirror neurons during storytelling. Hasson tracked their brain patterns and found the listener’s brain did indeed mirror the teller, but at a slight delay. Then, as the story evolved, the listener mirrored the storyteller synchronously with no delay. Finally, and here’s the Vulcan “Mind Meld” part—the listener’s brain started accurately mirroring the teller’s brain before the teller got to that part of the story. They were truly on the same wave length. Hasson calls this “neural coupling.” Neural coupling demonstrates the power of narrative to trigger an empathetic simulation in the listener’s brain.

Meanwhile, Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Toronto, Canada, studies people’s brain patterns while they read stories. He’s discovered as we read text, our brain simulates the real world aspects triggered by the text—in our brain we simulate what we read about–we can hear, smell, feel and even mimic motion. His later studies found a correlation between those who are more avid readers of fiction with a greater capacity for empathy. He hypothesizes that reading fiction exercises the unique human ability to mirror what others think and feel and thus build empathy. At an Ogilvy Public Relations session on neuroscience and narrative at the Global PR Summit 2012, Mar went on to say that immersive stories actually are quite effective at changing minds: “The more people are transported into the world of a narrative, the more they feel immersed in a story, the more likely they are to change their beliefs to be more consistent with those expressed in the world of narrative.” Mar says that even if you tell subjects that this story is a work of fiction and not necessarily true, it still can influence their views. In other words, this implicit experiencing the views of others works better than an explicit argument.

But does it have to be fiction to work? Can’t persuasive essays change minds? Mar says, “The distinction isn’t really between fiction and non-fiction, but between stories and exposition. Making something narrative in nature—a story—regardless if you label it a true story or a fictional story, the more absorbing it is, the more people will be absorbed and immersed and possibly the more persuasive it will be.”

One of Mar’s experiments compared the impact of reading a Chekhov short story with a version of the story rewritten like a trial transcript. Mar’s research stated: “People who read the short story experienced significantly greater change in personality than the control group and individuals in this group also reported being more emotionally moved. Further analyses indicated that their change in personality was mediated by the emotions evoked by the text. Emotion, therefore, was central to the experience of change in the ways in which they viewed themselves, that is to say in their personality.”[3]

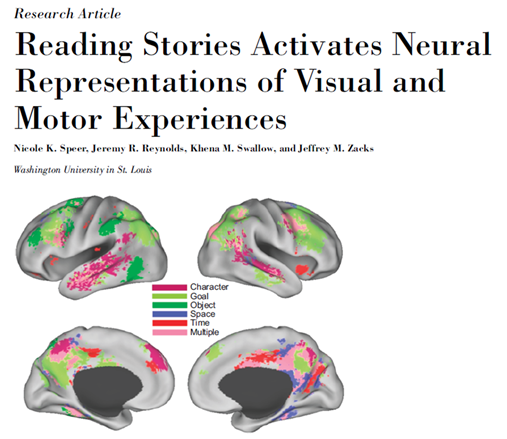

The findings of a group of scientists at Washington University in Saint Louis bolster this notion of the human brain as ultimate simulator. They found that as subjects read stories, their brain would recreate actions, sensory experiences and even the intentions and coals of characters in a story.[4]

The findings of a group of scientists at Washington University in Saint Louis bolster this notion of the human brain as ultimate simulator. They found that as subjects read stories, their brain would recreate actions, sensory experiences and even the intentions and coals of characters in a story.[4]

Professor of social psychology and breakthrough researcher on narrative transport, Melanie C. Green, wrote that “Despite the normative presumption that individuals should form their beliefs based only on factual sources, common experience suggests–and my data confirms–that individuals often base real-world judgments on information from fiction. Humans are practiced at creating possible worlds, and when confronted with a fictional situation, individuals appear to be basing their judgments on plausibility rather than accuracy.”[5] Green, like Mar, said her research reveals that while an expository or evidentiary approach to persuasion may fall prey to the backfire effect, the power of transporting people through narrative can succeed.

At an Ogilvy PR session of the Global PR Summit 2013, Green says the power comes through “stepping into the lives of these characters. It’s being immersive, it’s being enjoyable. We’re not being critical, we’re not counter-arguing. So those kinds of things can break down some of the initial barrier that we’re going to have to be persuaded. But what it can also do once we’re in that narrative world is create those connections that are so important… We’re taking the perspective of these people, and the empathy that it creates goes out and we carry it beyond just those few moments when we were thinking about the story.”[6]

The discovery of mirror neurons, the further findings of neural coupling, and the narrative transportation findings of Mar and Green all add up to a crucial storytelling technique and approach often completely overlooked by or abandoned by corporations: The old creative writing saw of “show, don’t tell” becomes more relevant than ever. That little rule of thumb sounds easy, but pulling it off is more difficult. But the positive impact of doing it well can be huge. While writers may have always known that “show, don’t tell” was intuitively the right approach, now brain science backs that up.

“Telling” refers to expository writing, plot summary and Powerpoint bullets, while “showing” refers to furnishing the empty mind through creating rich, detailed descriptions and imagery. Telling instructs you how to feel or what to do; showing creates the emotion, mood and character that allow you to infer what is going on. Showing is much tougher to pull off but when successful, allows the audience to take control of the narrative, to picture it in their own minds and own it emotionally. Public relations and corporate communications nearly always take the “telling” route via messaging. But instead, to be more effective, communicators need to adopt a novelist’s approach of creating a scene, and a character struggling in a specific world. Telling brings us no imagery while showing creates a movie in the listener’s mind. Such a movie triggers mirror neurons, those roots of human empathy. Neuroscientists have discovered that as we read stories, the brain recreates them as though we ourselves are experiencing them physically.

“Telling” refers to expository writing, plot summary and Powerpoint bullets, while “showing” refers to furnishing the empty mind through creating rich, detailed descriptions and imagery. Telling instructs you how to feel or what to do; showing creates the emotion, mood and character that allow you to infer what is going on. Showing is much tougher to pull off but when successful, allows the audience to take control of the narrative, to picture it in their own minds and own it emotionally. Public relations and corporate communications nearly always take the “telling” route via messaging. But instead, to be more effective, communicators need to adopt a novelist’s approach of creating a scene, and a character struggling in a specific world. Telling brings us no imagery while showing creates a movie in the listener’s mind. Such a movie triggers mirror neurons, those roots of human empathy. Neuroscientists have discovered that as we read stories, the brain recreates them as though we ourselves are experiencing them physically.

Take this example. Imagine you wanted to change minds about same-sex marriage. Look at a side-by-side comparison. The first is a website called “Minnesota for Marriage.” It lays out all the “myths & facts.” This is well-organized and logical but most likely will not change minds because it does not tap into the emotional governors of decision-making nor does it transport the audience.

When constructing such a narrative, social psychology also guides us into another important choice: should the story feature one, single protagonist or several? Here the findings are singularly clear.

Nobel Prize Laureate Thomas Schelling who in 1968 developed the notion of the “identifiable victim effect” where results found that people were far more willing to come to the aid of a clearly identified individual than to a whole group in need.

In a more recent piece by researcher Paul Slovic of the firm Decision Research, he determined that there is a steep falloff of sympathy and willingness to donate to a group versus an identifiable individual. In fact the drop off starts with just two people.

Then, in 2007, Wharton School marketing professor Deborah Small discovered a powerful new piece of information.[7] Not only do we stop caring after the first individual, statistics and facts drain us of all empathy. Her research compared the willingness of subjects to donate when they had three different options. The first was a story about an individual with a name (a little girl named Rokia) and photo and no statistics at all. The second was a set of statistics showing the magnitude of the problem and how badly they need donations. And the third combined the story and the statistics as a combination of narrative and fact. The lone story of the single individual always beat any version that included statistics or sets of facts. Why do we feel so much more sympathy toward the less scientific version, the so-called “identifiable victim” version? Loewenstein[8] conjectures the reasons include vividness (“vivid details may result in a perceived familiarity with the victim”). This fits with research from Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman wherein he identified and named a bias the “simulation heuristic.” He discovered that if you more readily imagine a scenario or picture it, you weight it more heavily and think it to be more true than a conceptual or factual version.

Yet think of all the public relations and corporate communications efforts usually pay no heed to these findings. Think how many have depended on analytical, logical “facts vs. myths” approaches, piling on the evidence of their argument, creating a backfire. Or cleansing the emotion and vividness from the narrative in an effort to be taken seriously. Or think of how many times you have seen a collage or montage of smiling employees (“teamwork!”) instead of one, lone fully-developed story of an individual.

Christopher Graves is the Global Chairman of Ogilvy Public Relations, Chair of The PR Council and a Trustee for IPR.

[1] “Mirror Neurons,” NOVA, airdate January 25, 2005, PBS

[2] “I Feel Your Pain,” by Gordy Slack in Slate, November 5, 2007

[3]“ Emotion and narrative fiction: Interactive influences before, during, and after reading” by Raymond Mar et al, 2010

[4] “Reading Stories Activates Neural Representations of Visual and Motor Experiences” By Nicole K. Speer, Jeremy R. Reynolds, Khena M. Swallow, and Jeffrey M. Zacks, 2009

[5] Melanie C. Green, Research Statement, 2012 (Dept. of Psychology, UNC Chapel Hill

[6] Melanie C. Green, interview with Christopher Graves at Holmes Global PR Summit 2013

[7] “Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought on donations to identifiable and statistical victims” by Small, Loewenstein and Slovic. University of Pennsylvania, 2005.

[8] “Explaining the ‘Identifiable Victim Effect’” by Jenni & Loewenstein, 1997