Stakeholder engagement has risen on the public relations agenda recently mostly due to the introduction of social media and new hybrid forms of marketing, advertising, and public relations. New technologies have made it possible for organizational messages to have direct stakeholder audience access but only if they are used properly. This article distinguishes between three different types of stakeholder relationships: the positively engaged faith-holders, the negatively engaged hateholders, and fakeholders the unauthentic persona produced by Astroturf and algorithms. The article suggests that it is the future task of public relations practitioners to support the faith-holders, engage the hateholders and reveal the fakeholders.

Download PDF:Understanding Stakeholder Engagement: Faith-holders, Hateholders & Fakeholders

Vilma Luoma-aho, Ph.D.

Professor of Organizational Communication & Public Relations

Department of Communication

University of Jyväskylä

PO Box 35 (OPK), FIN 40014 * Tel. +358 40 8053 098

vilma.luoma-aho@jyu.fi

@vilmaluo

Abstract: Stakeholder engagement has risen on the agenda of public relations recently mostly due to the introduction of real-time media and new hybrid forms of marketing, advertising and public relations. Engaging stakeholders is not a simple task in the information rich environment, and can be compared to a pinball match; organizational messages now have direct access, but often bounce randomly around in the online environment. To simplify measurement of public relations in this complex, unpredictable environment, this article distinguishes between three different types of stakeholder relationships: the positively engaged faith-holders, the negatively engaged hateholders, and fakeholders the unauthentic persona produced by astroturf and algorithms. The paper suggests that it is the future task of public relations professionals to support the faith-holders, engage the hateholders and reveal the fakeholders. This mostly conceptual article introduces these three emerging groups, gives examples of all three and ponders their significance and their implications for public relations in the future.

Executive Summary

Stakeholder engagement has always been central for public relations, but has received more attention recently due to the introduction of real-time media and new hybrid forms of marketing, advertising and public relations. Engaging stakeholders is not a simple task in the information rich environment, and can be compared to a pinball match; organizational messages now have direct access, but often bounce randomly around in the online environment.

To simplify measurement of engagement in public relations in this complex, unpredictable environment, this article distinguishes between three different types of stakeholder relationships: the positively engaged faith-holders, the negatively engaged hateholders, and fakeholders the unauthentic persona produced by astroturf and algorithms. This mostly conceptual article introduces these three emerging groups, gives examples of all three and ponders their significance and their implications for public relations in the future.

Four propositions are presented:

1) Priority in stakeholder relations should be placed on the faith-holders of high trust and long-term commitment, as they further influence all other stakeholders. In practice, this will mean slowly redirecting organizational finances and efforts from the previously prevailing focus on crisis management and dealing with Hateholder interactions toward support and service desired by the faith-holders.

2) Hateholders should not be ignored but seen as a potential future faith-holder group if their issues are addressed. More research is needed to understand how the in process of reconciliation would occur practice, but understanding that hate may not be the final emotion these stakeholders feel toward the organization will encourage professionals.

3) Public relations should monitor the stakeholder arenas to detect possible fakeholders, and if detected, invite the hidden influencer to dialogue. This remains an ideal, as in there are always hateholders and fakeholders that cannot be reasoned with.

4) All stakeholders may move from positive to negative engagement or from negative to positive engagement unexpectedly. Static maps of stakeholder emotion are outdated and need to be replaced with dynamic, realtime understanding of how stakeholders feel.

The paper suggests that it is the future task of public relations professionals to support the faith-holders, engage the hateholders and reveal the fakeholders. Understanding all three groups is needed, as they all contribute to organizational legitimacy.

Introduction

Stakeholder engagement has risen on the agenda of public relations recently mostly due to the introduction of social media and new forms of contribution media (Castells, 2009). How stakeholders engage with brands and organizations matters in this environment where peers and “people just like me” have become the most trusted sources for information and experiences both online and offline (Edelman, 2013). Engaging stakeholders is not a simple task in the information rich environment, and can be compared to a pinball match; organizational messages now have direct access, but often bounce randomly around in the online environment (Hennig-Thuray et al. 2010). At the world public relations forum in Madrid, Spain in September 2014, Paul Holmes of the Holmesreport suggested that public relations measurement in essence was about which stakeholders can recommend us, and which are harmful. This article elaborates on that idea by introducing three different stakeholder groups in regards to the timely topic of stakeholder engagement.

The Melbourne Mandate (2012) views stakeholder engagement as central for sustaining positive organization-public relationships. Though some scholars prefer to talk of ‘publics’ (Aldoory & Grunig, 2012) instead of ‘stakeholders’, mutual dependence remains the central idea. According to the situational theory of publics (Grunig & Huang, 2000), different groups become active or latent depending on their interest in the issue. In the online environment such changes may occur almost in real-time, and problem recognition, constraint recognition and level of involvement may all change unexpectedly. In fact, publics and stakeholders not previously understood to be of importance for organizations and issues may be activated through third parties and the media, and complicate the traditional understanding of who matters and why for organizations (Luoma-aho & Paloviita, 2010).

Organizations have been established as targets of strong emotions ranging from hate to love and even passion (Fineman, 1993). Stakeholders in general tend to expect greater engagement than before, and the ‘feeling rules’ (Hochschild, 1979) about what feeling is or is not appropriate to a given social setting are constantly re-negotiated online. Trust toward the organization and inside the organization (Kramer & Tyler 1996) is central in this era when organizations aim to deal with public displays of positive and negative emotion. Trust is believed to be the foundation of a strong organizational character that all communication is built on.

For many organizations customers and stakeholders are resources to be utilized. This thinking, however, is becoming outdated when these resources have actual access into publishing their experiences to potentially large audiences. Engagement as a construct brings the relationship between stakeholders and organizations on a more equal level: brands and organizations have to interact with stakeholders on various issue arenas (Luoma-aho & Vos, 2010) or rhetoric arenas (Coombs & Holladay, 2013) outside their control. As engagement becomes the trend, there is a shift toward seeing stakeholders as long-term assets to be protected and cultivated. Management of these emerging relationships, however, has become challenging in the era not dominated by organizations. Engagement cannot be forced, and the ideal is to tempt stakeholders into a relationship through providing extra value and contributing to issues relevant to them.

The value of engagement lies in its understanding of dialogue dynamics and enabled participation. Beyond public relations, several other related traditions and disciplines have taken interest in stakeholder engagement including advertising (Wang 2006), environmental management (Amaeshi & Crane, 2006), marketing (Brodie et al. 2011) and in the form of reader engagement, even online journalism (Mersey et al. 2009). What all these disciplines agree on, however, is the new emphasis on the importance of dialogic nature of the relationship between stakeholders and organizations (DuMars, Sitkiewicz & Fogel 2010). In general, engagement refers to the level of interaction a stakeholder shows toward an organization, and this interaction is believed to influence stakeholder thoughts, actions and emotions toward the organization (Brodie, Hollebeek, Juric & Ilic, 2011).

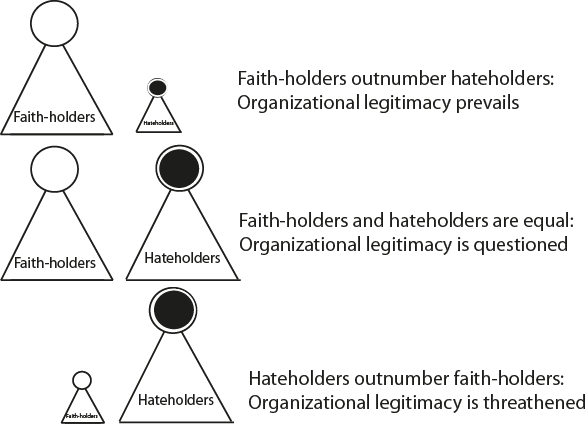

In the age of poly-contextual corporate legitimacy (Holmstrom, 2004) where organizations and brands must increasingly negotiate their licence to exist with various different stakeholder groups on different issue arenas of influence (Luoma-aho & Vos, 2010), the role stakeholders play for organizational survival can be seen to have increased. In this unpredictable environment organizations often look for stakeholder support, yet simultaneously have to prepare for opposition (McDonald & Cokley, 2013). It is an environment of increased stakeholder power and emotion, and new forms of stakeholding can be distinguished: the positively engaged authentic faith-holders and the negatively engaged hateholders. As portrayed in figure 1, the logic behind these is that organizational legitimacy can only be maintained in the long term if the number of faith-holders exceeds the number of hateholders (author, 2010).

Figure 1. The division of faith-holders and hateholders and consequences to organizational legitimacy.

This article also introduces and the emerging astroturfed unauthentic fakeholders, that matter especially during times of challenged legitimacy. On issue arenas, sometimes all three groups are equal, and traditional modes of relationship cultivation and building do not work. This conceptual article introduces these three emerging stakeholder groups, and ponders their engagement type and their implications for public relations in the future. These new forms of stakeholders are especially apparent among the digital natives (Vodanovich et al. 2010) who instead of being passive consumers, increasingly expect to take part in content creation and have an influence on the products and services they consume. As many organizations and brands today are still run by digital immigrants, understanding the new forms of engagement remains a challenge.

The paper is organized as follows: First, the development of stakeholder engagement from uses and gratifications theory to modern customer engagement is examined. Second, positive engagement and faith-holders are introduced. Third, the idea of negative engagement of hateholders is described. Finally, fakeholders of fake engagement through astroturf are discussed, and four propositions are put forth about these groups and the role of public relations in the future. The paper concludes that to cultivate organizational social capital in the long term and maintain legitimacy, public relations professionals need to support the faith-holders, engage the hateholders and reveal the fakeholders.

From uses and gratifications to engagement

Though a rising buzz word, customer engagement is actually not a new phenomenon. The history of public relations is all about engaging different customers and consumers, though the concepts applied may differ. Other origins of engagement could be understood to reside in uses and gratification theory (Katz, 1959) describing the readers’ needs and media use according to their own needs. Though media has changed since the origins of the theory, the basic idea of being able to choose remains (Prior, 2005) and recent studies have identified new uses along the lines of socializing and monitoring. For internet in general, Tewksbury and Althaus (2000) identified new uses such as passing time and surveillance. Similarly, Parker and Plank (2000) noted surveillance and excitement among other more traditional uses. Along with engagement, also social sharing is taking place online. In studies focusing on the use of social media, new uses include monetary compensation, personal status and establishing virtual community (Song et al., 2004) as well as getting recognition (Leung, 2009), advice and new points of view (Quan-Haase & Young, 2010). Social identity building has also received support as a common reason behind positive engagement on forums such as Facebook (Zhang & Carroll, 2010). What organizations and brands are hoping, is to benefit from these new uses and gratification, and engaging customers is suggested to do so (Hennig-Thuray et al. 2010).

Engagement understands the importance of building a relationship with stakeholders beyond purchases. Engagement can be defined as a favourable “customer’s behavioural manifestation” towards a brand, product or an organization (Van Doorn et al. 2010), consisting of also cognitive and emotional aspects. As stakeholder engagement is primarily concerned with the relationship between organizations and their stakeholders with a focus on dialogue, consultation and participation (Amaeshi & Crane, 2006), stakeholder engagement is central for public relations. Engaged customers who voluntarily interact with an organization and its products are beneficial for the organizations through increased trust (Andriof et al., 2002), recommendations (Kumar et al. 2010) and loyalty and co-creation (Kumar et al. 2010; Roberts & Albert 2010). It is clear that such positively engaged stakeholders are important for organizational success, and Coombs & Holladay (2014, 45) note that after crises “organizational reputations and brands suffered less damage among favourably predisposed publics than indifferent or negative publics”.

Though most literature takes engagement to be merely a positive phenomenon, recently also its negative sides have received attention. Recent studies have confirmed the logic of negative engagement to differ from that of positive engagement (Smith et al., 2013). The idea behind negative engagement is that negative attitudes can contribute to negative behaviors (Kumar et al., 2010; van Doorn et al., 2010), which may affect organizational reputation (Muntinga et al. 2011; Coombs and Holladay 2014). Negative engagement has thus far mostly been studied in the context of crises (Jin, Pang and Cameron 2010; Coombs & Holladay, 2007), but not all negative engagement is crises-related. Moreover, negative engagement needs to be better distinguished from disengagement (Bowden-Everson & Neumann, 2013), as the processes of positive engagement, disengagement and negative engagement differ. Recent research has also noted that the type of service in question shapes engagement and disengagement, as utilitarian type services tempt less engagement and easier disengagement than participative services (Bowden, Gabbott & Naumann, 2014). The different faith-holders, hateholders and fakeholders are next addressed in more detail, and examples of each are provided in current organizational online settings.

Faith-holders

In the attention economy the role of recommendations and peer reviews has increased. This has emphasized the importance of those stakeholders who trust the organization and are willing to recommend it. Similar to the idea of net promotor scores and being able recommend the product or service, the stakeholders with positive experiences make up the organizational social capital that can be drawn on in both good and bad times (Luoma-aho, 2009); their trust is not easily shaken by individual incidents. These stakeholders can be titled Faith-holders, and they are defined as positively engaged stakeholders who trust and like the organization or brand and support it via their beliefs, emotions and behaviours.

Most fan communities can be seen as faith-holder groups of the organization they support (Apple, Soccer teams, organic food), yet the true role of faith-holders emerges often during crisis, where the loyal customers and fans are able to keep a crisis from escalating. Examples include the 2012 #teamblackberry case, where false accusations toward the brand were publicly corrected by the support of its loyal high profile fans. Similarly, when the insurance company Aviva in 2012 faced a crisis through an accidental email sent to all employees about terminating their contract, its employees were faith-holders who trusted the company enough to not immediately outrage. Instead, they asked the company for explanations for this behaviour and received apologies, saving the company’s reputation and finances. Some other recent forms of positive engagmenet and faith-holder maintenance projects include the call for contrubtions through My Starbucks Idea and putting popular fans’ ideas into production at Lego.

Faith-holders can exist on all three levels of cognitions, emotions and behaviour, but the most beneficial are the ones manifesting all three: beliefs that the organization or brand is good; feeling positive emotions toward the brand or organization and act out in a way that actually builds social capital for the brand. This social capital can take the form of reputation building or positive word of mouth. In fact, Coombs & Holladay (2014) talk of favourably predisposed publics and summarize marketing research to explain that positive expectations, brand loyalty and familiarity together protect organizations and brands reputations, especially during and after crises. In an unpredictable environment, faith-holders may hold the key to maintaining a positive organizational reputation on the different issue arenas (Hon & Yang, 2011). The faith-holder concept highlights the importance of individual experiences: it does not matter how satisfied the organization thinks its stakeholders to be, but instead the stakeholders’ personal experiences and expectations are central. Building on cognitive-mediational theory (Lazarus, 1991), the emotions stakeholders have toward the organization shape their interpretations and appraisal of it. This appraisal contributes to their behaviour and choices, making faith-holders credible brand- and organizational advocates. Faith-holders trust the organization, and their positive experiences make them a beneficial organizational resource (Fineman, 1993).

The proposition related to the faith-holder concept is that the maintenance of existing stakeholders and customers is more important than the acquisition of new ones, as the satisfied stakeholders will attract new stakeholders by themselves (Parasuraman et al, 1985). Satisfaction can be defined as customer evaluations of quality (The American Customer Satisfaction Index 2014), and it is often related to certain expectations, either of individual experiences or an overall cumulation of such experiences. Satisfaction of stakeholders provides also financial gains, as customer acquisition is costly (Virmani & Dash, 2013). Faith-holders embody stakeholder loyalty, and loyal stakeholders consume more and encourage others to do likewise (Fecikovà, 2004).

A stakeholder becomes a faith-holder simply when they engage positively with an organization or a brand. Bridging service quality with behaviour intentions, Choy et al. (2012) describe how technical and functional quality together with satisfaction contribute to behavioural intentions: for positive engagement to occur certain positive experiences are needed, whether mediated or personal. For engagement to be valuable, it must be public, such as comments or recommendations on social networking sites and other positive word of mouth. This highlights the importance of listening to stakeholders’ needs and expectations (Olkkonen & Luoma-aho, 2014), as only through meeting and exceeding expectations can lasting satisfaction occur. If stakeholder expectations are not met or they are violated, even previously satisfied stakeholders can turn negative (Creyer & Ross, 1997), even into hateholders, which are next discussed.

Hateholders

Hateholders are negatively engaged stakeholders who dislike or hate the brand or the organization and harm it via their behaviours (author, 2010). Hateholding does not occur on the level of mere dissatisfaction, but requires a clear target and stimulus, and is often the result of anger. Hateholding is a timely topic, as stakeholders today have several ways of showing their emotion and recruiting others to join in online. Moreover, negative reports are more credible than positive especially in the online environment (Chen & Lurie, 2013), and previous research shows that negative emotions resulting from discordant relationships may hinder interaction (Loewenstein, 1996).

Hateholders emerge often through negative experiences and act out as a result of unresponsiveness from the organizational side, both inside and outside the organization. Internal examples of hateholders include the leaking of confidential information by Edward Snowden in the US Government, or the Domino’s pizza crisis of bad employee joking or the famous United Breaks Guitars –song, but also more systematic coalitions or activist groups can be understood as hateholders due to their active negative engagement.

Ranging from venting and sharing negative events to taking revenge on an organization, hateholder expressions of anger vary in severity. Many hateholder outbursts are understood as individual events of venting; regulating individual emotions (Parlamis, 2012), but little research exists on the value of such venting. Moreover, individual vents may have major consequences when experiences and negative word of mouth spread fast in the online environment. The online environment also serves as a collective memory re-vitalizing even once forgotten issues. Expectations affect assessments and perceptions (Creyer & Ross, 1997), and failure to meet expectations plays a large role in causing negative emotions including regret, dissatisfaction, sadness and anger. In fact, failure of service can be described as a situation where a service experience violates “prior held expectations” (Zeelenberg & Peeters, 2004).

Whereas dissatisfaction may be general and untargeted, anger usually has a clear target (Kuppens et al., 2003) making it of more relevance for brands and organizations. In fact, anger is among the most common emotions leading to negative engagement behaviours (Sánchez-García & Currás-Pérez, 2011). Negative emotions lead to negative engagement especially in cases where an organization or individual is assumed to be blamed for an event or failure. Further, other accountability is the strongest prediction of stakeholder anger (Kuppens et al., 2003), and anger and efficacy together may produce anger activism (Turner, 2007). This anger activism is here understood as hateholding. Anger rarely results without any actual cause, and certain events have been suggested to trigger anger such as frustration from goal obstacles, other accountability of cause, perceptions of unfairness and lack of control of evolving events (Kuppens et al., 2003).

Though organizations and brands often fear the negatively engaged “complainers”, hateholders actually embody a valuable opportunity for the organization to detect neglected issues, problems and shortcomings in need of improvement. In fact, hateholders can be understood to care enough to engage, and hence once their experienced wrongs are atoned, they could become even faith-holders. Hateholders always require active monitoring from organizations and brands, and not all hateholders can be transformed into faith-holders despite organizational efforts. There are also cases where hateholders have no personal experiences, but merely engage with malicious aims such as trolling (Hardaker, 2010). At times hateholders are not really people but un-authentic fake persona constructed by machines or software, as in the case of fakeholders, who are next discussed.

Fakeholders

Fakeholders are opinions, socio-bots and stakeholders artificially generated by either individuals or persona-creating software and algorithms to either oppose or support an issue. These unauthentic faith-holders or fakeholders do not exist in reality, and their influence appears larger than it in practice is. Behind the rise of fakeholders is the rising trust in “people like me” (Edelman Trust Barometer, 2012). Research suggests much of online reviews to be generated and fake, despite their trustworthy reputation and consumers’ heavy reliance on them (Kolivos & Kuperman, 2012). As the value of customer reviews increases, so does the pressure to produce favourable content.

Fakeholder support is related to the often applied concept of astoturf. As a concept, astroturf originates from the installation of real-looking fake grass on sports arenas by the brand AstroTurf (Tigner 2010). Famous for the fakeholder world it was made by senator Bentsen’s 1986 comment of how he could tell the difference between real support and “astoturf”, referring to the letters he was receiving that had in fact been generated by the insurance industry (Malbon, 2013). Fakeholders may be products of astroturf, but also emerge on a smaller scale. Astroturfing refers to fake stakeholders’ artificial grassroots campaigns that are created by unethical public relations practitioners or lobbyists via fake personalities or persona management software. Astroturfing aims to influence or support via “synthetic advocacy efforts” (McNutt & Boland 2007, 165). Examples of fakeholders can be seen on the level of individuals and organizations or nations. Fakeholder examples can be found on several customer review sites through fake reviews, but a larger scale example include the Monsanto case of building artificial attacks to question research findings that found genetically modified plants where they were not allowed, the fake Walmarting Across America blog set up by Edelman, or the fake research claiming Internet Explorer users as less intelligent by Aptiquant.

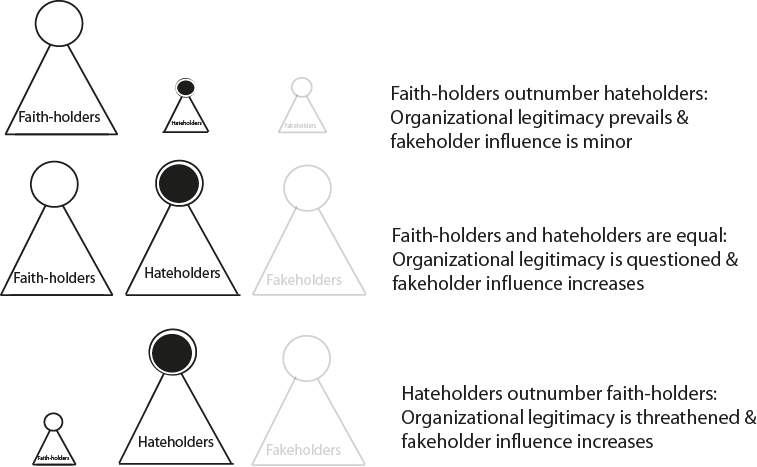

Though often not included in the meaning, the source behind the fakeholders and astroturf is of central importance, but alike propaganda, the actual sources attempt to hide. Fakeholders are products artificially created foster some aim or issue. Often they are combined with fake organizations or associations, with an aim to simply appear respectable and powerful and lobby or hinder some individuals’, government’s or organization’s interests. Fakeholding in practice is carried out via sock puppets or meat puppets controlled by sophisticated persona management software. On the larger scale, astoturf has been used by governments such as China, where they reportedly paid 5 mao for each pro-government message online. As seen in figure 2, the role of fakeholders increases in times when legitimacy is questioned or challenged, and stakeholders are looking for confirmation about their engagement for better or worse. In addition, sometimes fakeholders can also be the cause of the questioned legitimacy, as in the Monsanto case.

Figure 2. The role of fakeholder influence increases in times when organizational legitimacy is questioned or threathened.

Fakeholders represent a negative issue for public relations, as many public relations practitioners and companies have been associated with astroturf practices (Lyon & Maxwell, 2004). The subsidies of such attempts can be monetary payments, or other benefits including access to the companies’ phone bank equipment and personnel. In some cases, astroturfers will act as members of the grassroots groups when recruiting real stakeholders. The codes of ethics of public relations associations strongly prohibit astroturfing due to its deceptive nature (Cho et al. 2011).

Organizations and brands hoping to distinguish between their real stakeholders and those responses created through algorithms and robots find themselves in novel situations: can certain stakeholders be ignored? Though the actual messages of fakeholders may be ignored, they still can cause real damage through translating unexpected new stakeholder groups into hateholders (Luoma-aho & Paloviita, 2010). All stakeholders are not equally capable of distinguishing astroturf, and real individuals may unknowingly support fake grassroots movements. Active monitoring of fakeholders is required, and though in practice distinguishing fakeholders may prove difficult, organizations and brands could benefit from proactive stance to approach potential fake groups directly via inviting them to engage in person and face to face.

Propositions and Discussion

Organizations and brands are dealing with an increasingly complex environment of stakeholder relations: today competition has turned global, consumers are fickle and anyone can bring down the long-established reputation of an organization in an instant. Overall, stakeholder management has expired, as relations can no longer be controlled by organizations or brands (Luoma-aho & Vos, 2010; Shirky, 2008). This has made understanding of the relationship dynamics more urgent, as secondary competition of organizational messages increases along with customer reviews and online communities. As “people just like me” have become most trusted sources (Edelman, 2013), brands and organizations are looking for both authentic and unauthentic means to influence stakeholders. On the other hand, this has made the efforts of public relations more visible, as customers and stakeholders are increasingly understood to be long-term resources.

In this dynamic environment, faith-holders are understood to make up the core relationships that in times of turbulence support organizations and brands through their trust and good experiences. Faith-holders are social capital for organizations (author, 2005), and they represent an underused resource for many organizations, as the traditional thinking is toward recruiting new customers instead of keeping the existing regulars satisfied. When financial savings are sought, the role of faith-holders should be emphasized, as they often cost less and offer more than new customer acquisition (Parasuraman et al, 1985). Faith-holders may hold the key to maintaining organizational legitimacy on the different issue arenas. Many issues of transparency and advocacy will also be solved when faith-holders are given a voice of their own. A central task for future public relations is hence proposed to be the empowering and enabling of faith-holders. Hence, Proposition 1: Priority in stakeholder relations should be placed on the faith-holders of high trust and long-term commitment, as they further influence all other stakeholders. In practice, this will mean slowly redirecting organizational finances and efforts from the previously prevailing focus on crisis management and dealing with Hateholder interactions toward support and service desired by the faith-holders.

Simultaneously, the rise of hateholders has proven problematic for brands and organizations. The strong negative emotions of stakeholders are often left unapproached, making hateholding even stronger. As anger has a clear target, organizations and brands should focus on the relationship dynamics of hateholders to discover the root of the problem. As hateholders seldom come as a surprise for organizations, the importance of monitoring should be highlighted to catch the early warning signs of emerging hateholders. As it is difficult to incorporate information not matching expectations and existing knowledge structures (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953), more research should be targeted at the negative affect experienced by hateholders, and communication that would not conflict with their existing values or beliefs. The more valued and institutionally dependent an individual is on existing values, the more challenging conflicting information becomes” (Beesley, 2005; 270). For public relations, the hateholders are a challenge but simultaneously a resource for improvement: The negative responses identify areas in dire need of improvement. In fact, in some cases collaboration with hateholders may be fruitful, as their outside eyes identify processes internally missed. Once the roots of the negative engagement are addressed, these stakeholders may sometimes even be turned into faith-holders. Hence Proposition 2: Hateholders should not be ignored but seen as a potential future faith-holder group if their issues are addressed. More research is needed to understand how the in process of reconciliation would occur practice, but understanding that hate may not be the final emotion these stakeholders feel toward the organization will encourage professionals.

Fakeholders are a product of unethical influence and public relations magnified with modern technology. Harmful for both organizations and stakeholders themselves, fakeholders may be produced to support or to oppose brands and organizations. What makes these groups challenging, is their non-human nature and lack of sympathy: there is no way to build “a relationship” with fakeholders, yet opinions produced by them may affect masses and harm organizations and brands. Even some positive fakeholders may prove problematic, as they may invite challenging groups or individuals into the discussion. What is needed for public relations is tools to better distinguish astroturf, enforced codes of conduct and guidelines on how to intervene the non-human interaction appearing to be much like stakeholder relations. At present, public relations can only act as the antenna of the organization to detect astroturf, but they are best suited to do so as they hold the general picture of the different relationships with the organization. Hence Proposition 3: Public relations should monitor the stakeholder arenas to detect possible fakeholders, and if detected, invite the hidden influencer to dialogue. Moreover, the faith-holders could be asked to contribute to the process. This remains an ideal, as in there are always hateholders and fakeholders that cannot be reasoned with. However, if in the future these different groups increasingly gain voice, it will be the well-trained faith-holders who rise to support the organization from hateholders and call out the fakeholders that emerge. It is the future task of the public relations professionals to support the faith-holders, engage the hateholders and reveal the fakeholders. Understanding all three groups is needed, as they all contribute to organizational legitimacy. Achieving this ideal state remains the present challenge. However, as public relations as a discipline is well equipped to understand relationship dynamics, it is a task worth undertaking despite the challenging settings.

The rise of faith-holders, hateholders and fakeholders both internal and external call for new theory and practices. Public relations as a field must start to acknowledge the heightened importance of emotions in society today and their role for organizational legitimacy. Faith-holders and hateholders seek for interaction and engagement, even a relationship with the organization, and this invitation should not be ignored. Internal hateholders and faith-holder are the most important ones to be acknowledged and should take priority as relationships are analysed. Future studies should address the difference between internal and external faith-holders and hateholders, as well as measure their actual contribution to organizational reputation and legitimacy. Moreover, as the environment today is more turbulent than before consisting of both human and non-human influences and real-time activation of passive stakeholders, it is becoming dangerous to view stakeholders are static members of any group. Hence Proposition 4: All stakeholders may move from positive to negative engagement or from negative to positive engagement unexpectedly. Depending on issues and agendas, the membership in one group can easily change to the other, and this calls for new alertness and monitoring ability from public relations professionals. Focus should instead of stakeholder group membership or emotion be placed on the level of activity and engagement as well as the issues and agendas driving the different stakeholders.

Public Relations as a practice and through it also its measurement have become increasingly complicated in the online environment. Though these three groups are generalizations of much more complex issues, this division into positive, negative and fakes marks a clear point of departure for public relations and its measurement. Further studies are needed to elaborate and test these divisions. As the buzzword of engagement also receives more research attention, the expectations for engagement by hateholders and faith-holders should also be studied. Engaging the different stakeholders in practice will be all about “balancing and integrating multiple relationships and multiple objectives” (Freeman and McVea, 2001), and hence future studies should also address the ideal levels and types of engagement for each specific group. For the industry on the whole, mechanisms that distinguish and authenticate online reviews are also urgently needed to prohibit reputational damage caused by some unethical practitioners and agencies behind fakeholders. Moreover, the professional standards and ethical guidelines may need revisions in light of the rise of fakeholders, and even concerning the tools and strategies on the engagement of hateholders.

References

Aldoory, L. & Grunig, J. (2012) The Rise and Fall of Hot-Issue Publics: Relationships that Develop From Media Coverage of Events and Crises. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6, 93-108.

Amaeshi, K. & Crane, A. (2006) Stakeholder Engagement: A Mechanism for Sustainable Aviation, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 13; 245-260.

Andriof, J., Husted, B., Waddock, S. & Rahmann, SS. 2002. Introduction. In Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking – Theory, Responsibility and Engagement, Andriof J, Waddock S, Husted B, Rahmann SS (eds). Greenleaf: Sheffield; 9–16.

Beesley, L. (2005) The management of emotion in collaborative tourism research settings, Tourism Management, 26(2005), 261-275.

Bowden-Everson, J. and Naumann, K. (2013). Us versus Them: The operation of customer engagement and customer disengagement within a local government service setting. ANZMAC conference proceedings. Auckland, New Zealand.

Bowden, J., Gabbott, M. & Naumann, K. (2014). Service relationships and the customer disengagement – engagement conundrum, Journal of Marketing Management.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Juric, B. and Ilic, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research. 14(3), 252-271.

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A, Juric, B. and Hollebeek, L. D. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis, Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105-114.

Coombs, T. & Holladay, S. (2014) How publics react to crisis communication efforts. Comparing crisis response reactions across sub-arenas. Journal of Communication Management, 18(1), 40-57.

Chen, Z. & Lurie, N.H, (2013). Temporal Contiguity and Negativity Bias in the Impact of Online Word of Mouth. Journal of Marketing Research 50(4) 463-475.

Choy, J-Y., Lam, Siew-Yong & Lee, T-C. 2012. Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: Review of Literature and Conceptual Model Development. International Journal of Academic Research. Vol. 4. No. 3.

Creyer, E. & Ross, W.T. (1997). The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: do consumers really care about business ethics? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 14(6), 421-432.

van Doorn et al. 2010. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253-266.

DuMars, B., Sitkiewicz, D. and Fogel, N. (2010). Learning to listen: Understanding New Influencers and Measuring Conversations for Meaningful Insights. In the Digital Reset: Communicating in an era of engagement. A Guide to Engaging Audiences through Social Media. Edelman: New Media Academic Summit, June 23-24, New York.

Dutton, W.H., Blank, G. 2011. Next Generation Users: The Internet in Britain. Oxford Internet Survey 2011. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford.

Fecikovà, I. 2004. Research and concepts: An index method for measurement of customer satisfaction. The TQM Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 57–66.

Fineman, S. (1993).Organizations as Emotional Areanas. Pp. 9-35. In: S. Fineman (Ed.)

Emotion in Organizations Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Grunig, J. & Huang, Y-H. (2000), From Organizational Effectiveness to Relationship Indicators: Antecedents of Relationships, Public Relations Strategies, and Relationship Outcomes, in Ledingham, J. & Bruning, S. (Eds.), Public Relations as Relationship Management. A Relational Approach to the Study and practice of Public Relations, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 23–54.

Hardaker, C. (2010) Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated-communication. Journal of Politeness Research, Vol 6, pp. 215-242.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E. C., Friege, C., Gensler, S., Lobschat, L., Rangaswamy, A. & Skiera, B. 2010. The Impact of New Media on Customer Relationships. Journal of Service Research, 13(3) 311-330.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion Work, Feeling Rules and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85:551-575.

Holmström, S. (2004). The Reflective Paradigm of Public Relations. In van Ruler, B. & Verĉiĉ, D. (eds.) Public Relations and Communication Management in Europe. A Nation-by-Nation Introduction to Public Relations Theory and practise. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin.

Hong, S. Y. & Yang, S.-U. (2011). Public engagement in supportive communication behaviors towards an organization: Effects of relational satisfaction and organizational reputation in public relations management. Journal of Public Relations Research. 23(2), pp. 191-217.

Hovland, C., Janis, I., & Kelley, H. (1953). Communication and persuasion: Psychological studies of opinion change. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Katz E (1959) Mass communication research and the study of popular culture: An editorial note on a possible future for this journal. Studies in Public Communication 2: 1–6.

Kaye, BK & Johnson, TJ. (2002) Online and in the know: Uses and gratifications of the Web for political information. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 46(1): 54–71.

Kolivos, E. & Kuperman, A. (2012) “Web Of Lies — Legal Implications Of Astroturfing.” Keeping Good Companies, 64(1), 38-41.

Kramer, R.M. & Tyler, T.R. 1996. Trust in organization: frontiers of theory and research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Kumar et al. 2010. Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. Journal of Service Research 13(3) 297-310.

Kuppens, P., Van Mechelen, I., Smits, D. J., & De Boeck, P. (2003). The appraisal basis of anger: specificity, necessity and sufficiency of components. Emotion, 3(3), 254.

Lazarus, R.S. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Leung, L. (2009) User generated content on the internet: An examination of gratifications, civic engagement and psychological empowerment. New Media & Society 11(8): 1327–1347.

Lev-On, A. (2011) Communication, community, crisis: Mapping uses and gratifications in the contemporary media environment, New Media & Society, 14(1) 98–116

Lin, C. & Jeffres, L (1998) Predicting adoption of multimedia cable service. Journalism Quarterly 75: 251–275.

Loewenstein, G. F. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65, 272–292.

Luoma-aho, V. (2010), Emotional Stakeholders: A threat to organizational legitimacy? Paper presented at the ICA Conference 2010, on panel: “Nothing more than feelings”, available online: http://jyu.academia.edu/VilmaLuomaaho/Papers/185612/Emotional-stakeholders–A-Threat-to-Organizational-Legitimacy-

Luoma-aho, V. & Paloviita, A. (2010) Actor-networking stakeholder theory for corporate communications, Corporate Communications: An International Journal 15(1), 47-69.

Luoma-aho, V. & Vos, M. 2010. Towards a more dinamic stakeholder model: acknowledging multiple issue arena. Corporate communication: An international journal. 15(3), 315-331.

Lyon, T. P. & Maxwell, J. W. (2004). Astroturf: Interest Group Lobbying and Corporate Srategy. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. 13(4). 561-597.

Malbon, J. (2013). Taking Fake Online Consumer Reviews Seriously. Journal of Consumer Policy. 36: 139-157.

McNutt, J. & Boland K. (2007). Astroturf, Technology and the Future of Community Mobilization: Implications for Nonprofit Theory. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. Vol. XXXIV. No. 3. 165-178.

Mersey, R. D., Malthouse, E. D. and Calder, B. J. (2010). Engagement with Online Media. Journal of Media Business Studies. 7(2), 39-56.

McDonald, L. M. & Cokley, J. (2013). Prepare for anger, look for love: A ready reckoner for crisis scenario planners. PRism 10(1), http://www.prismjournal.org/fileadmin/10_1/McDonald_Cokley.pdf ).

Olkkonen, L. & Luoma-aho, V. (2014) ”Public Relations as expectation management?”, Journal of Communication Management, 18 (3), 222-239.

Papacharissi, Z & Rubin, A (2000) Predictors of Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 44(2): 175–196.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. The Journal of Marketing. Vol. 49, pp. 41-50.

Parlamis, J. D. (2012). Venting as emotion regulation: The influence of venting responses and respondent identity on anger and emotional tone. International Journal of Conflict Management, 23(1), 77-96.

Parker BJ and Plank RE (2000) A uses and gratifications perspective on the Internet as a new information source. American Business Review 18(2): 43–9.

Prior M (2005) News vs. entertainment: How increasing media choice widens gaps in political knowledge and turnout. American Journal of Political Science 49: 577–592.

Quan-Haase A and Young AL (2010) Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30: 350–361.

Raacke J & Bonds-Raacke J (2008) MySpace and Facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 11(2): 169–174.

Roberts & Alpert. (2010). Total customer engagement. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 19(3) 198–209.

Ruggiero TE (2000) Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication & Society 3(1): 3–37.

Sánchez-García, I., & Currás-Pérez, R. (2011). Effects of Dissatisfaction in Tourist Services: The role of anger and regret. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1397-1406.

Smith, S. D., Juric, B. and Niu, J. (2013). Negative Consumer Brand Engagement: An Exploratory Study of “I Hate Facebook” Blogs. ANZMAC conference proceedings. Auckland, New Zealand

Tewksbury D and Althaus SL (2000) An examination of motivations for using the World Wide Web. Communication Research Reports 17(2): 127–138.

Tigner, R. (2010). Online Astroturfing and the European Union’s Unfair Commercial Practices Directive. URL: http://www.droit-eco-ulb.be/fileadmin/fichiers/Ronan_Tigner_-_Online_astroturfing.pdf (20.3.2014)

Turner, M. M. (2007). Using emotion in risk communication: The anger activism model. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 114-119.

Virmani, M. & Dash, M.K. (2013). Modelling Customer Satisfaction for Business Services. Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 51–60.

Wang, A. (2006). Advertising Engagement: A Driver of Message Involvement on Message Effects. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 355-368.

Zeelenberg, M. & Pieters, R (2004). Beyond valence in customer dissatisfaction: a review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. Journal of Business Research, 57(4), pp. 445-455

Zhang, S. & Carroll, J.M. (2010), Social Identity in Facebook community life, International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 2(4), 64-76.