This article is a part of the Commission on Measurement & Evaluation. This article originally appears in The Communication Director.

In an age of disinformation and filter bubbles, navigating a fragmented and disrupted media landscape requires, more than ever before, a finely tuned moral compass. So where does that leave the ethical communicator?

The birth of public relations was dominated by Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee – often referred to as the fathers of PR. Bernays saw the PR practitioner as having a distinct social purpose: “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in a democratic society” (in Propaganda, 1928).

However, it was Lee, rather than Bernays, who introduced ethics to public relations with his 1906 Declaration of Principles to distinguish his practice from advertising: “…to supply the press and public of the United States prompt and accurate information concerning subjects which it is of value and interest to the public to know about.”

In modern times, several organizations, such as the European Association of Communication Directors and the Arthur W. Page Society, promote principles and guidelines on standards for public relations and corporate communications. However, ‘ethical PR’ is a phrase many see as an oxymoron. A practice that never really managed to shake off its close ties with propaganda surely can’t claim to be ethical at its core?

Preparing a course on PR, Ethics and Professional Responsibility for the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications this winter semester made me reflect on the ethical challenges and dilemmas – some new, some not so – that surround and pervade the field of public relations.

Where We Are Today

First, there is the question whether or not PR is actually a profession, with formal standards of professionalism – such as law, accountancy, medicine or architecture. Unlike professions that require formal certification, a young practitioner can join a PR firm with, say, a history or a biology degree and with no practical experience. No formal and controlled barriers to entry exist, no professional qualifications and conversion into practice.

There are, however, attempts to establish continual professional development, the operation within an ethical framework and a code of conduct, an open exchange between research and practice, and a sharing of knowledge.

Then there is PR’s problem with its own PR: the perception that this is a discipline struggling to adhere to its own professional and ethical standards. Recent examples of malpractice, such as the shutting down of two British communication firms, Bell Pottinger in 2017 and Cambridge Analytica in 2018, as a result of unethical behaviour has only added to an already murky reputation.

There is a sense that old school Anglo-Saxon PR has always been and will always be a bit rough around the edges. Sir Tim Bell, founder of Bell Pottinger and formerly Margaret Thatcher’s spin doctor and campaign strategist, is known for the statement “Morality is a job for priests, not PR men”.

Third, there is the sense that trust in institutions by stakeholders and citizens is shrinking, and that public relations and communication – rather than fostering trusted relationships between organisations and their publics – are contributing to the continued erosion.

When PR is about building and maintaining relationships, and truth is the key to successful trusting relationships: then it becomes clear why the public erosion of trust in an age of post-truth is so problematic and so dangerous for the PR and communication function (I recommend the Edelman Trust Barometer, and various recent contributions by Edelman CEO and industry thought-leader Richard Edelman, for further reading).

And lastly, there are ethical considerations arising from the rapid and disruptive innovation cycles in information technology and social media, from the privacy rights of users to the consequences of filter bubbles and the promises of psychographic microtargeting of highly segmented publics.

So the need for ethics is immediate and hands-on. Ethics is not a collection of abstract statements, to be framed and hung on a wall. Ethics is everyday practice, small decisions adding up to larger decisions, adding up to an organisation’s character. In a market starved for talent, young practitioners seek out organisations that align with their own values and principles.

Stakeholders and shareholders increasingly care about values and hold companies to account for their products and services.

In her textbook Ethics in Public Relations, Patricia Parsons describes applied ethics as the ability to draw a black line through a grey area. As a practitioner, when faced with an ethical dilemma, how do you make your decision? Where do you draw the line?

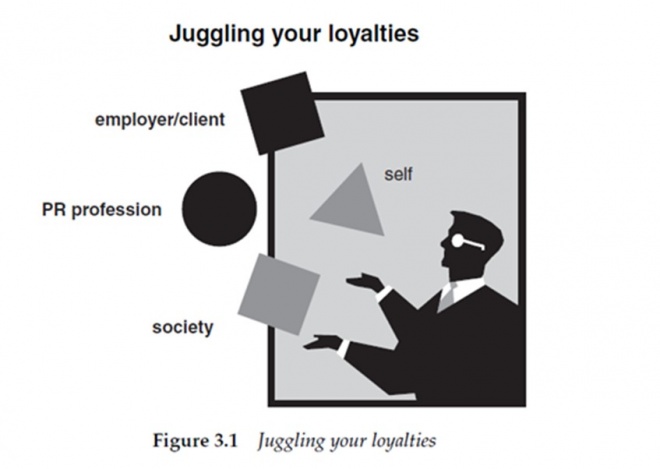

The challenges are manifold, to do with a practitioner’s accountability, duties and loyalties. For example, the duty and loyalty to their company or client (what happens if my morals come in conflict with professional duties?). Or to their professional field: what are the agreed standards of practice? Then there is the area of social responsibility: the duty to society, to the public interest, to do no harm.

Most important, though, is a practitioner’s duty to themselves. It starts with our own norms and values, our own moral compass. The better we know our moral selves, the better we will become in ethical decision making personally and professionally. An ethical business is ultimately a collection of moral individuals.

And as individuals, we learn to juggle our loyalties when faced with difficult decisions and dilemmas: do we take the well-paid job in spite of the company’s poor public image? Are we prepared to promote products that can cause harm to consumers? And what about defending ‘alternative facts’ on behalf of our client?

Ethical decision-making comes down to three basic steps: one, moral awareness, that is recognising the existence of an ethical dilemma; two, moral judgement, i.e. deciding what is right and wrong; and three, ethical behaviour: taking action to do the right thing. This is where professional codes help. They are a contract with society, rather than an instruction manual.

Harvard ethics professor Ralph Potter’s four step process, known as the Potter Box, is an established framework to make ethical decisions. It starts by establishing facts – define the situation you’re in. Then it looks at values – do they differ among stakeholders and potentially affected parties? Next is the application of principles.

For example, do we take a utilitarian or consequentialist approach which considers potential outcomes first, or are we bound by duty ethics where rules and processes are the main consideration? The final step in the Potter Box relates to loyalties, where the practitioner is back to juggling the loyalties to self, company or client, profession and society. In every single case, then, a conscious ethical decision comes down to that black line that we draw through an area of grey – and under which circumstances we are prepared to moved it.

Education and training – on personal and on professional level – are central to ethical decision-making. In an industry (re)establishing itself in a world in flux, ethical standards are also constantly being revisited, revaluated and redefined by professional bodies worldwide.

The new Global Capabilities Framework by the Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management, is the latest overview of required knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours for public relations practitioners. One of the main capabilities: “To work within an ethical framework on behalf of the organisation, in line with professional and societal expectations.”

Where To From Here?

As Professor Ana Adi writes elsewhere in this issue, our VUCA world demands new approaches, both in education, and practice. Institutions leading the way will focus on models of networked collaboration and values-based choices, where accountability, reliability, transparency, fairness and flexibility are handled in a more self-organised way, and the role of trusted advisor and consultant to the organisation becomes the key function.

However, theory must prove itself in practice. In his now infamous BBC Newsnight interview about Bell Pottinger’s deal with the Guptas in South Africa, Lord Bell explained how he attended a critical meeting as a “father figure”, as these meetings always needed to have someone senior in them.

That approach leaves little scope for less senior corporate communicators to make the right decision, based on an ethical framework, in situations they feel uncomfortable with.

Ethical thinking and doing in organisations start with leadership. In a 2014 article on ethical leadership for the Institute of Public Relations, Dr. Rita Linjuan Men describes leadership as “a nested influence in an organisation that affects organisational culture, structures, communication climates, systems, and the attitudes and behaviors of employees.”

She goes on to define the seven traits of ethical leaders:

- Be fair. Treat employees fairly, don’t practice favoritism, and don’t hold employees accountable for things they shouldn’t be responsible for.

- Empower employees. Give opportunities for employees to join in organisational decision-making and to express their opinions, concerns, and feelings.

- Clarify roles. Be crystal clear about what you expect from employees, including their performance levels, responsibilities, and boundaries.

- Genuinely care. Show respect, support, care, understanding, and compassion. Make employees feel included and appreciated.

- Be accountable. Always deliver on what you promise, be consistent in what you say and do, and be accountable for your words and actions.

- Give ethical guidance. Lead by example, explain ethical standards clearly, and promote and reward ethical conduct among employees.

- Be environmental-friendly. Pay attention to sustainability issues, consider the effect of your actions beyond yourself or the interests of the organisation, and care for the welfare of the society.

Without leaders walking the talk of ethical practice, practitioners cannot be expected to up their games in ethical terms. However, leadership doesn’t just mean ‘C-suite’. Leadership happens on all levels of organisations, and the seven traits apply everywhere. Taking responsibility for one’s actions is the first step.

Richard Edelman made a strong point in a keynote speech at USC Annenberg in May this year, when he called for highly established and publicly stated ethical standards. Such standards, whether they are called Page or Global Principles, code of conduct or code of ethics, will put the discipline – if not profession – of public relations in a good position for its practitioners to thrive with ethical focus in an ever-challenging, ever-changing environment.

![]()

Thomas Stoeckle is co-founder of SmallDataForum, and Associate Chair of the Institute for Public Relations (IPR) Measurement Commission. Follow him on Twitter @ThomasStoeckle1.

Thomas Stoeckle is co-founder of SmallDataForum, and Associate Chair of the Institute for Public Relations (IPR) Measurement Commission. Follow him on Twitter @ThomasStoeckle1.