Every company is concerned about its reputation — for lots of good reasons. But we don’t talk much about the relationship between a company’s reputation and its success in public affairs. If the public doesn’t trust you, are you more likely to be regulated? If Congress likes you, will it pass favorable laws? If your CEO volunteers to advise the president on government policy, will that generate goodwill?

If you’re speed-reading like most people, I’ll save you some time. The answers are “yes,” “maybe” and “probably not.”

The annual Public Affairs Pulse survey, a poll of 2,201 Americans conducted in September 2017, sheds light on public attitudes and expectations for business and government. This year the survey focused on the impact of reputation on a firm’s ability to achieve its public policy goals.

Understanding the interplay between communications and government relations is challenging because both functions are difficult to measure. In communications, can you place a precise value on media stories that don’t run or are less negative than expected? In government relations, what’s the ROI when a compromise bill is passed that could have been worse, but also could have been better?

The Pulse survey, conducted by polling firm Morning Consult, illustrates the public relations/public policy nexus in several important ways.

Trust and Regulation

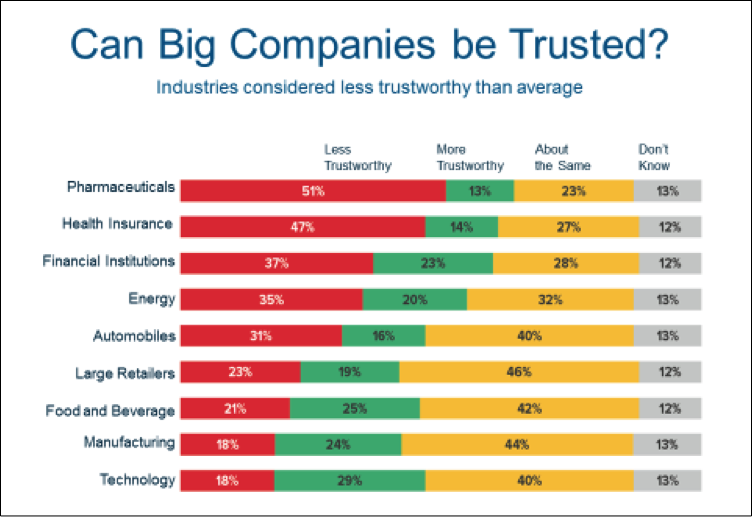

First, respondents were asked to rate the trustworthiness of nine major corporate sectors in comparison to each other.

Technology companies had the best score with 29 percent of the public calling them more trustworthy than average and only 18 percent calling them less trustworthy. Manufacturing companies didn’t quite match the technology sector with above average scores (24 percent), but they also had only 18 percent of the public labeling them as less trustworthy.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the sector considered most untrustworthy was pharmaceutical firms, with 51 percent of respondents saying they were less trustworthy than average. Right in front of drug companies were health insurance companies (47 percent called them less trustworthy) and banks (37 percent called them less trustworthy).

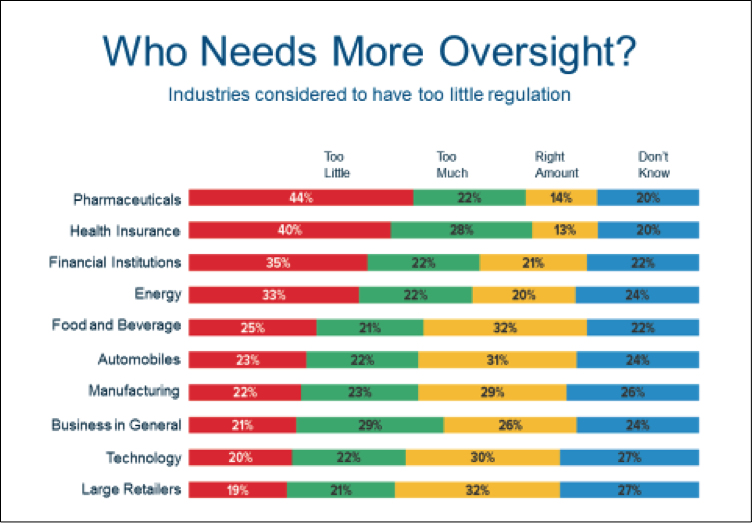

Next, respondents were asked for their views on whether a corporate sector was under-regulated, over-regulated or subject to the right amount of regulation.

Once again, technology was in a virtual tie for first place — this time with large retail companies. Twenty-two percent said tech firms were over-regulated and only 20 percent thought they were under-regulated.

The bottom three sectors were the same three who trailed in trustworthiness: pharmaceutical firms, health insurance companies and banks. Forty-four percent of Americans said drug companies were under-regulated and only 22 percent said they faced too much regulation.

A remarkable correlation? Not really. When you think about it, government regulation is an act of distrust. If an industry is widely trusted, the public often assumes that further government scrutiny is unwarranted. On the other hand, if a sector doesn’t appear to be acting in the public interest, consumers and legislators are more likely to support tighter rules.

This is not to say that having a good reputation insulates an industry from new regulations or a less favorable tax system. Especially now, when Congress is struggling to pass major, complex legislation, there will be winners who don’t deserve to win and losers who don’t deserve to lose. In many ways, Washington, D.C., is the land of unintended consequences.

But when legislative trade-offs are being made, having a positive reputation is still a huge advantage. If you need proof, just ask the organizations representing small business interests. Because of small business’s high favorability rating (87 percent in the Pulse survey), both major parties often carve out regulatory exemptions for that sector.

Business and Politics

Poll questions also compared the popularity of two influential and controversial groups — elected officials in Washington, D.C., and corporate CEOs. And it revealed some eye-opening results.

The Pulse survey uncovered one of the few opinions on which Trump and Clinton voters agree: that national politicians have low honesty and ethical standards. While it’s not surprising that only 6 percent of Clinton voters said national politicians were highly ethical, it’s remarkable that only 7 percent of Trump voters concurred with this assessment.

After all, the Republican Party has control over the White House and both houses of Congress. The people now holding the reins of power are largely the people sent there by Trump voters. Yet the percentages of Clinton and Trump supporters claiming Washington elected officials were dishonest were nearly identical (59 percent and 58 percent, respectively).

The bad news for big corporations is that, reputation-wise, CEOs scored only marginally better than D.C. politicians. While 9 percent of Americans said major company CEOs were highly ethical, 43 percent said they had low honesty and ethical standards. By comparison, small business CEOs received high scores for ethics from 41 percent of the public and low scores from only 5 percent.

If you’re looking to explain why business leaders are almost as distrusted as politicians, look no further than the executive compensation issue. Only 22 percent of Americans think major companies are doing a good job paying their top executives fairly, without overpaying them. And only 31 percent feel companies are doing a good job ensuring fair compensation of rank-and-file workers.

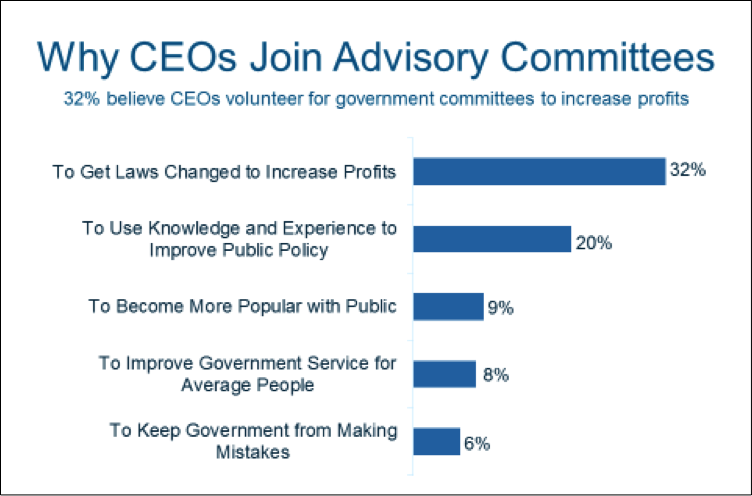

So, here’s a hypothetical question to ask yourself (a question that may not be so hypothetical for a few dozen large companies reading this article). If your CEO were asked to serve on a presidential advisory committee, would the public (A) thank him or her for serving their country, or would they (B) suspect the CEO had ulterior motives? If you chose A, you’re probably going to be disappointed.

One out of three Americans believe CEOs join these committees in order to increase company profits. And another 9 percent think CEOs join to become more popular with the public. What’s more, 28 percent see CEOs serving on advisory committees as actively endorsing the president, while only 39 percent think CEOs are still able to maintain their independent political views.

These findings are not really surprising. If the public already questions the ethics of major company CEOs and our nation’s political leaders, then it stands to reason that a committee putting them together in the same room must be up to no good.

When is Lobbying Acceptable?

Americans have a low opinion of lobbying because of scandals like the Jack Abramoff affair, but also because of long-term distrust of Washington politics. This opinion persists despite tighter lobbying laws, greater transparency and the fact that lobbying speech is protected under the First Amendment.

It turns out, however, that public cynicism about lobbying may be a popular view, but not a deeply held value. The Pulse survey finds the public largely approves of corporate lobbying when a company states specific reasons for its advocacy. In fact, 61 percent said lobbying to protect jobs was an acceptable form of corporate lobbying and only 15 percent disagreed. Majorities of Americans also approved of lobbying to level the playing field with competitors and support social causes.

This example provides a reminder that companies can gain credibility when they take time to explain their decisions and actions, and connect them to the public good. Smart political and business communicators make a point to localize and even personalize their messages.

Many professionals working in government relations often say their expertise is in public policy, not public relations. Nevertheless, these two functions are closely linked and need to be coordinated. One can earn you a political benefit; the other can earn you the benefit of the doubt.

Doug Pinkham is president of the Public Affairs Council, the leading global association for public affairs professionals. The Council, which is both nonpartisan and nonpolitical, has more than 700 member companies and associations. You can reach him at dpinkham@pac.org.

Doug Pinkham is president of the Public Affairs Council, the leading global association for public affairs professionals. The Council, which is both nonpartisan and nonpolitical, has more than 700 member companies and associations. You can reach him at dpinkham@pac.org.