Abstract: In this quantitative research study, the future of public relations practice and study is explored through the lens of professionalization and social roles. Specifically, this study evaluates the relationship between professionalization and social roles of public relations professionals. A survey of public relations professionals is used to build and test a model of professionalization and social roles constructs. The results revealed significant relationships between the three dimensions of professionalization and the two dimensions of social roles. Strong associations were found between institutionalization and external and internal social roles. Positive associations were found between specialization, as an indicator of professionalization, and internal and external social roles of public relations professionals. Results indicate that the greater the professionalization of the practice, the greater of the enactment of social roles of professionals.

Download Full Paper: An Intertwined Future: Exploring the Relationship between the Levels of Professionalization and Social Roles of Public Relations Professional

Juan-Carlos Molleda, Ph.D., Professor and Chair, Department of Public Relations of the College of Journalism and Communication at the University of Florida, academic trustee of the Institute for Public Relations, and Co-Director of the Latin American Communication Monitor

Sarabdeep Kochhar, Ph.D., Director of Research, Institute for Public Relations, APCO Worldwide, and University of Florida’s College of Journalism and Communications.

Ángeles Moreno, Ph.D., Professor, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Executive Director of the European Public Relations Research and Education Association, and Director Latin American Communication Monitor

Gabriel Stephen, Doctoral Student, University of Florida’s College of Journalism and Communications

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Looking towards the future of public relations, Richard Edelman (2011) stated that viability relied on the urgency and ability of professionals to adapt to the evolving roles of the practice. To address the evolving requirements of the industry, this study expounds upon two important topics of professionalization and social roles in public relations scholarship. J.E. Grunig and Hunt (1984) outlined two core professional values that are important for public relations work: respect for society and a common code of ethics. In the practice and study of public relations, the relationship between the levels of professionalization and social roles of professionals could help to further define the future of the public relations profession.

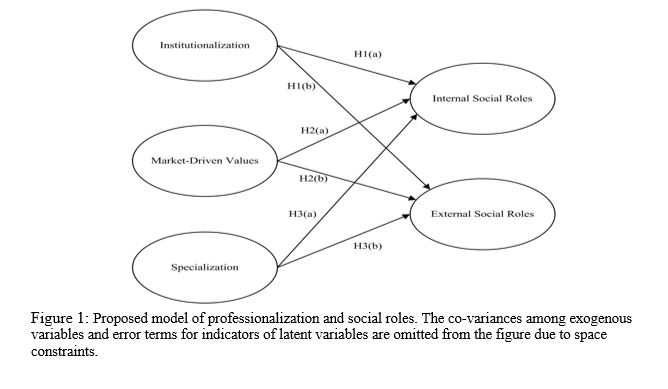

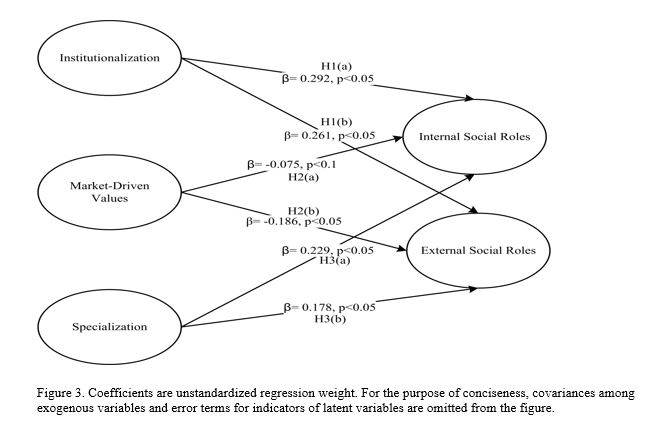

Over four decades, professionalization has been a core construct of public relations scholarship. This study uses the construct of levels of professionalization in public relations (as a sector of the labor market), instead of the professional orientation of who are in charge of the function in organizations and agencies, which has been the focus of most studies since the 1970s (J.E. Grunig, 1976; Nayman, McKee, & Lattimore, 1977; Wright, 1979). The connection between public relations and its social role has been frequently articulated in public relations literature. Scholars have long since claimed that public relations and social responsibility are not separate activities and, therefore, should not be evaluated separately (L’Etang, 1994). J.E. Grunig and Hunt (1984) stated that “public, or social, responsibility has become a major reason for an organization to have a public relations function, because the public relations professional can act as an ombudsman for the public inside the corporation” (p. 48). Based on the conceptualization of professionalization and social roles, and the relation between the two, we tested a model hypothesizing the relationship between the levels of professionalization and social roles of professionals: (H1a) institutionalization is positively associated with internal social roles of practitioners; (H1b) institutionalization is positively associated with external social roles of practitioners; (H2a) market-driven values is positively associated with internal social roles of practitioners; (H2b) market-driven values is positively associated with external social roles of practitioners; (H3a) specialization is positively associated with internal social roles of practitioners; (H3b) specialization is positively associated with external social roles of practitioners.

Survey results of public relations professionals in 10 Latin American countries were used as a basis of this study. The measurement items used in this study were developed from the original work of Freidson’s (1983, 2001) and Krause’s (1996) and the further conceptualization of professionalization by Molleda, Athaydes, and Suárez (2010). Sixteen items were used to assess the levels of professionalization of public relations in Latin America. A four-wave online survey was used to gather data for this study; the survey was active from October to November of 2009. A developed network of colleagues as well as a database of Latin American public relations professionals from trade associations helped with the data collection process. Invitations to participate in the study were sent to 2,290 practitioners in 19 countries. While 1,150 persons attempted to take the survey, 674 completed the questionnaire. Only 10 countries (N = 612) met the minimum requirements for inclusion set by the researchers: Argentina (N = 59), Brazil (N = 102), Chile (N = 38), Colombia (N = 104), Costa Rica (N = 67), Guatemala (N = 39), Mexico (N = 80), Panama (N = 23), Peru (N = 33), and Venezuela (N = 67).

Hypothesis 1(a) posited that institutionalization is positively associated with internal social roles of practitioners. This hypothesis was supported, β= .29 (B = .294, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This means that institutionalization is associated with the internal social roles of practitioners. Hypothesis 1(b) theorized positive association between institutionalization and external social roles of practitioners, β= .26 (B = .263, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This hypothesis was supported, which substantiates that institutionalization is related with external social roles of public relations professionals. Hypothesis 2(a) on market-driven values being positively associated with internal social roles of professionals, β= -.075 (B = -.074, S.E. = .41) was not supported reinforcing the social conscience “internal role” of a professional. Hypothesis 2(b) stated how market-driven values is positively associated with external social roles of professionals, β= -.186 (B = -.186, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This hypothesis was supported, connecting the factors of market-driven values of the profession to the external social roles a professional performs. Hypothesis 3(a) stating that specialization is positively associated with internal social roles, β= .22 (B = .230, S.E. = .38), p < .01 was supported extending the need for establishing a specialized body of knowledge for the profession and to regulate information and expertise within an organization or agency. Hypothesis 3(b) stating specialization is positively associated with external social roles, β= .17 (B = .178, S.E. = .38), p < .01 was also supported bringing together the external role capabilities and specialization aspect of the profession.

Confirmatory factor analysis, using structural equation modeling, resulted in a valid model. The model indicated that higher levels of professionalization (institutional, market-driven, and specialization) are positively related to the internal and external social roles of public relations professionals. This is a significant finding considering the increased relevance that public relations has accrued in all types of organizations; as a result, greatly impacting societies around the world. The goal of this study is to provide the public relations community with additional arguments in advocating for the professionalization of the practice and study of public relations. The study of professionalization of public relations as a sector of the labor market, instead of the professional characteristics of those in charge of this communications management and strategic advising function, allows for trade associations to keep stay abreast to all of the infrastructural and policy conditions needed to elevate the status of field of study. Results from this study could form the basis of executive professional training workshops and even create specific academic curricula for universities worldwide. These curricula can also encourage active discussions among the professionals represented by or members of trade associations and other leading institutions, such as foundations and think tanks for public relations education and strategic practice.

An Intertwined Future: Exploring the Relationship between the Levels of Professionalization and Social Roles of Public Relations Professionals

Introduction

Looking towards the future of public relations, Richard Edelman (2011) stated that viability relied on the urgency and ability of professionals to adapt to the evolving roles of the practice. To address the evolving requirements of the industry, this study will expound upon two important topics of professionalization and social roles in public relations scholarship. J.E. Grunig and Hunt (1984) outlined two core professional values that are important for public relations work: respect for society and a common code of ethics. For public relations, the relationship between the levels of professionalization in practice and scholarship, and the social roles of professionals in the field needs to be explored and analyzed. Further study could help define the future of the public relations profession. The purpose of this study is twofold: to advance the constructs of professionalization and social roles for public relations professionals, and to establish how the relationship between the two constructs may determine the future status of the public relations practice worldwide.

As a field of study and practice, public relations is lacking agreement in the outlining of descript processes for the profession. The evolution of public relations as a consecutive set of well-defined and mutually exclusive stages has been challenged (Lamme & Russell, 2010). However, “the rise of professionalization of public relations and journalism, codes of ethics, formal education programs, […] and the delineations among publicity, propaganda, public information, and public relations, all have created a framework over time through which understanding and practice of public relations is now filtered” (Lamme & Russell, 2010, p. 354).

Professionalization is a construct that still requires further conceptualization and analysis. For more than four decades, professionalization has been among the core constructs in public relations scholarship. Nevertheless, there is a lack of consensus about what dimensions of professionalization best describe the occupation. Having salience since the 1970s, the focus of most studies on professionalization in public relations has used the professional orientation of professionals’ framework (J.E. Grunig, 1976; Nayman, McKee, & Lattimore, 1977; Wright, 1979). This study uses the construct of levels of professionalization in public relations as a sector of the labor market. Beam (1990) argued for the study of professionalization from an occupational power relationship, stating that a sociological perspective goes beyond the individual level of analysis. Furthermore, a level of analysis focusing on the sector itself or on an occupational power relationship would facilitate cross-national comparisons in a region with an unequal stage of political and socioeconomic development (Molleda & Moreno, 2008).

This study focuses on the levels of professionalization as a major component of the aforementioned historical framework (Beam, 1990). Inspired by Lamme and Russell’s (2010) work, this study operates within the belief that public relations has benefited from an accumulated set of standards to guide its modern practice, and has experienced various levels of development in different parts of the world. Ketchum’s senior counsel and executive producer of the multimedia platform “Business in society,” John Paluszek (2007), stated that, in its finest sense, public relations is a global profession because it functions in the public interest in virtually every part of the interconnected world. Hence, the need to understand the levels of professionalization and the social roles of professionals has relevance in the development and globalization of the profession.

The connection between public relations and its social role has been frequently articulated in corresponding literature. Numerous scholars have long claimed that public relations and social responsibility are two constructs that should not be considered or evaluated separately (L’Etang, 1994). J.E. Grunig and Hunt (1984) stated, “public, or social, responsibility has become a major reason for an organization to have a public relations function, because the public relations professional can act as an ombudsman for the public inside the corporation” (p. 48). Boynton (2002) later probed into the relationship between professionalization and social responsibility of public relations professionals:

Social responsibility is considered both an element and an outcome of professionalism, which points to the potential duality of these concepts. That is, socially responsible behavior is both a professional attribute and a valued course of action for public relations professionals. (p. 256)

With the context provided by overviews of professionalization and social roles, this study’s purpose is to understand how the relation between the two constructs influence public relations research and practice. This study is based on the assumption that a better-informed community of professionals will contribute significantly to the improvement of accountability, transparency, and practice standards of the profession as a whole. The implications of such a study is necessary to bridge the gap between professionals and scholars who currently “live in different worlds” (van Ruler, 2005, p. 159). Therefore, this study will attempt to bring the two worlds together by better understanding and explaining the relationship between professionalization and social responsibility roles. Results from the study can inform public relations training and workshops and, further, encourage academic curriculum for universities worldwide.

Theoretical Framework

Professionalization of public relations is often defined as a multidimensional construct (David, 2004; Lages & Simkin, 2003). “Professional values are standards for action that are accepted by the practitioner and professional group and provide a framework for evaluating beliefs and attitudes that influence behavior,” Weis and Schank argued (1997, p. 366). Public relations professionals and scholars have long attempted to construct profession-wide ethical practices and core professional values. For example, Public Relations Review devoted an issue to the theme of ethics in 1989. Additionally, numerous professional associations in the industry have established codes or protocols of ethics to reflect a focus on professional values, some such associations include: Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management (GA), International Association of Business Communicators (IABC), and International Public Relations Association (IPRA), and Public Relations Society of America (PRSA). The Institute for Public Relations (IPR) included ethics as a category on its open-to-the-public research library.

Construct of Professionalization

One of the most prominent theoretical perspectives in sociology of the professions has been the trait approach – “which was dominant for much of the twentieth century” – and the power (or power/conflict) approach –“which emerged subsequently in the 1970s in opposition to the inadequacies of trait theorizing” (Burns, 2007, p. 70). According to Burns (2007), “the power approach chronicled types of self-interest (occupational closure, status, and economic rewards) as key drivers of professional action, instead of unreflectively accepting the definitions of professions themselves, the idea that altruism and public service defined who could really be counted as professions, as the trait approach had done” (p. 70).

The trait or phenomenological approach advocates for the study of how regular members of an occupation invoke the term profession in everyday use (Freidson, 1983). Researchers in this tradition have tried to articulate a set of core attributes that an occupation must satisfy to become a profession. McLeod and colleagues produced this attribute orientation in the 1960s and 1970s (e.g., McLeod & Hawley, 1964); this approach later greatly characterized the work on professionalization in journalism. The index was also sufficient for application in other mass communication fields, including public relations (Bissland & Rentner, 1989; Hallahan, 1974; Nayman, McKee, & Lattimore, 1977; Wright, 1979).

McLeod-Hawley’s professional orientation scale was criticized for being methodologically unsatisfactory (Ferguson, 1981). Further critical reviews of the scale concluded that the tool was theoretically inadequate. Beam (1990) proposed that the study of professionalization should be done at an organizational level (Beam, 1990).

Despite criticism of the McLeod-Hawley index, public relations scholars have continued to use the scale for the study of professionalization (Coombs, Holladay, Hasenauer, & Signitzer; 1994). For the purpose of both trade and academic use, Cameron, Sallot, and Lariscy (1996) conducted a literature review on public relations professionalization and concluded, “Only four [topical] articles argue from data, from the empirical base that best informs our attempts to define professionalism and then assess our progress to professional standard” (p. 46). The authors were referring to the work of Gitter and Jaspers (1982), Ryan (1986), Judd (1989), and Rentner and Bissland (1990).

Molleda, Athaydes, and Suárez (2010) furthered the study of professionalization through comparative sector level of analysis. The authors articulated and tested a new index drawn from the work of two sociologists in the profession (i.e., Freidson, 2001; Krause, 1996). Molleda et al. (2010) assessed the professionalization levels of public relations in Latin America and tested an index based on 16 items that were developed from Freidson’s (1983, 2001) and Krause’s (1996) conceptualizations of professionalization.

Construct of Social Roles

The social roles of organizations has undergone radical change over the year. Bendall (2005) stated that the view of organizations had gone from characterizations, such as enemy and ungrateful beneficiaries, to change-agents and environmental sustainable enterprises; this was especially salient in developing countries (Visser, 2007). Scholars have articulated and even advocated for a social responsibility role of the public relations professional, as well as the profession (e.g., J.E. Grunig, 2000; J.E. Grunig &White, 1992; Holtzhausen, 2000; Holtzhausen, 2002; Holtzhausen & Voto, 2002; Kruckeberg, 2000; Kruckeberg & Starck, 1988; K. A. Leeper, 1996; R. Leeper, 2001; Starck & Kruckeberg, 2001). Verčič and J.E. Grunig (2000) attempted to track the development of corporate social responsibility (CSR) research with that of public relations field from a reactive, proactive, interactive, and strategic point of view. The researchers later suggested changes in the role of public relations practitioner from adapting to the environment, to helping organizations co-create the environment.

Molleda (2002) introduced the first known operationalization of social roles of Latin American public relations professionals by designing a multi-item scale and testing it in Brazil and Colombia. Molleda and Ferguson (2004) further analyzed the data to advance the description of the different “social roles” of Brazilian public relations professionals. They analyzed internal and external social role items and validated four social role dimensions: (1) “Ethics and social responsibility,” (2) “Employee well-being,” (3) “Community well-being,” and (4) “Government harmony” or harmony between organizations and governments. The authors concluded that the social role indicators and the factors extracted “explain the actions that a professional performs to increase his or her involvement as the social conscience of the organization and perhaps as a change agent or agent of social transformation” (p. 346).

Molleda (2001) explained that the Latin American perspective of public relations focuses on community interests; contributions to the well-being of the human environment where organizations operate; the historical and socio-economic reality of the region; social transformation and change agency; the ideas of freedom, justice, harmony, equality and respect for human dignity; and confidence without manipulation using communication to reach accord, consensus, and integration. The evolving social roles of the Latin American professional can be defined as change agents or agents of social transformation who use organizational resources to engage internal and external publics in activities and programs that better their lives.

The communitarian perspective of public relations also informs the social role construct. Hallahan (2004) summarized this perspective and concluded that public relations professionals have different roles to play in three forms of community building (i.e., involving, nurturing, and organizing). Community-building, according to Hallahan (2004), involves “integration of people and the organizations they create into a functional collectivity that strives toward common or compatible goals” (p. 259). Community involvement is an attempt by the organization to participate in a cause-related group or the existing community. Community nurturing, according to Hallahan, is an attempt by an organization at “fostering the economic, political, social, and cultural vitality of communities in which people and organizations or causes are members” (p. 261). Community organizing is an attempt by an organization to create new communities from the grassroots level and improve economic or social conditions in a particular neighborhood.

Molleda (2011) conducted a quantitative comparative online survey to assess the internal and external dimensions of the social roles of Latin American public relations professionals in 10 countries. Brazilian, Costa Rican, and Venezuelan participants expressed higher evaluation for social role tasks than the other seven countries’ participants. Participants from Guatemala and Panama rated the social roles indicators the lowest. Overall, the internal social role factor obtained higher mean scores than the external factor indicating that employees are a priority.

Interdependence between professionalization and social roles

An individual’s core value is a reflection of who the individual is and what this individual is about. Behavior of an individual is guided by personally held principles, beliefs, and values. The same can be thought of a professional value, which resonates with the profession and the people who practice it. For example, according to PRSA, the value of member reputation depends upon the ethical conduct of everyone affiliated with organization. Each individual sets an example for each other – as well as other professionals – by their pursuit of excellence with powerful standards of performance, professionalization, and ethical conduct. David (2004) viewed the reconciliation of values between an organization and its publics as a three-way compromise between individual, organizational, and social values.

Professionals enact the reflective role “to analyze changing standards and values and standpoints in society and discuss these with members of the organization in order to adjust the standards and values/standpoints of the organization accordingly” (van Ruler & Verčič, 2004, p. 6). The reflective role empowers the diverse stakeholders of an organization and the society as a whole. In studying public relations professionals, Wright (1979) did not find a significant association between being professional and being socially responsible. He explained, on the basis of this examination that it is not possible to claim that one of these conditions help to cause the other” (p. 31). Wright’s research may result in a different outcome today. Since the 1970s, the profession has reached a level of maturity and evolution that may demand a higher level of commitment with stakeholders and the society at large.

Bivins (1993) noted that public relations’ “clarification of its ethical obligation to serve the public interest is vital if it is to accomplish its goal and if it is to be accepted as a legitimate profession by society” (p. 117). He also emphasized the importance of “public interest” in defining professionalization. Therefore, attaining professionalization in public relations depends largely on acting in a socially responsible manner.

Pieczka and L’Etang (2001), in their review of the literature on the power-control perspective of professionalization, concluded that their analysis on the traits of a profession should “help professionals to understand their own roles, not simply in terms of managerial/technical levels of organizational position but also in a much broader context in terms of the power of the occupational role in society” (p. 234).

Coleman and Wilkins (2009) studied the moral development of public relations professionals. They concluded that professionals’ ethical reasoning “can be a way for the profession to the claim the authority that will support responsible conduct” (p. 337). Kim and Reber (2009) explored how public relations professionals’ professionalization is associated with their attitudes toward corporate social responsibility (CSR). Results showed that professionals with high professionalization have more positive attitudes toward CSR. Professionals’ longer time in the job and larger public relations department size positively affect professionalization. Women have more positive attitudes toward CSR than men, and older professionals have more positive attitudes toward CSR than younger professionals.

Based on the conceptualization of professionalization and social roles and the relation between the two, we propose to test a model hypothesizing the relationship between levels of professionalization and social roles of professionals (see Fig. 1). The hypotheses are as follows:

- Hypothesis 1a: Institutionalization is positively associated with internal social roles of professionals.

- Hypothesis 1b: Institutionalization is positively associated with external social roles of professionals.

- Hypothesis 2a: Market-driven values is positively associated with internal social roles of professionals.

- Hypothesis 2b: Market-driven values is positively associated with external social roles of professionals.

- Hypothesis 3a: Specialization is positively associated with internal social roles of professionals.

- Hypothesis 3b: Specialization is positively associated with external social roles of professionals.

Method

The study used previous studies to extend the concepts of professionalization and social roles of professionals. Survey results of public relations professionals in 10 Latin American countries were used as a basis of the study. The measurement items were developed from the Freidson’s (1983, 2001) and Krause’s (1996) conceptualization of professionalization by Molleda, Athaydes, and Suárez (2010). The 16 items were used to assess the professionalization levels of public relations in Latin America.

The social roles of public relations practitioner was measured by using the scale developed by Molleda (2011). He, in a comparative study, established a clear connection between the actions and decisions of the public relations and communication management professionals along with their internal and external social environments. The original social role scale was previously used for research in Latin America (Molleda & Ferguson, 2004; Molleda & Suárez, 2006). The original Brazilian study included 44 items and the Colombian study included 30. Molleda (2011) collapsed and re-analyzed the common items of both original data sets gathered in Brazil and Colombia to identify a 13 item scale.

Survey Instrument

The data used for the study was gathered using a four-wave online survey designed in Qualtrics which was active from October to November of 2009. A developed network of colleagues and a database of Latin American public relations professionals from the trade associations helped with the data collection. Invitations to participate in the study were sent to 2,290 professionals in 19 countries. Only 1,150 attempted to take the survey and 674 completed the questionnaire. However, only 10 countries (N = 612) met the minimum numbers of observations set by the researchers: Argentina (N = 59), Brazil (N = 102), Chile (N = 38), Colombia (N = 104), Costa Rica (N = 67), Guatemala (N = 39), Mexico (N = 80), Panama (N = 23), Peru (N = 33), and Venezuela (N = 67).Thus, the response rate was 29 percent. The 14 items on perceptions of professionalization and 13 items on the social roles were rated using a five-point Likert scale, in which one was strongly disagree and five was strongly agree by public relations and communication management professionals.

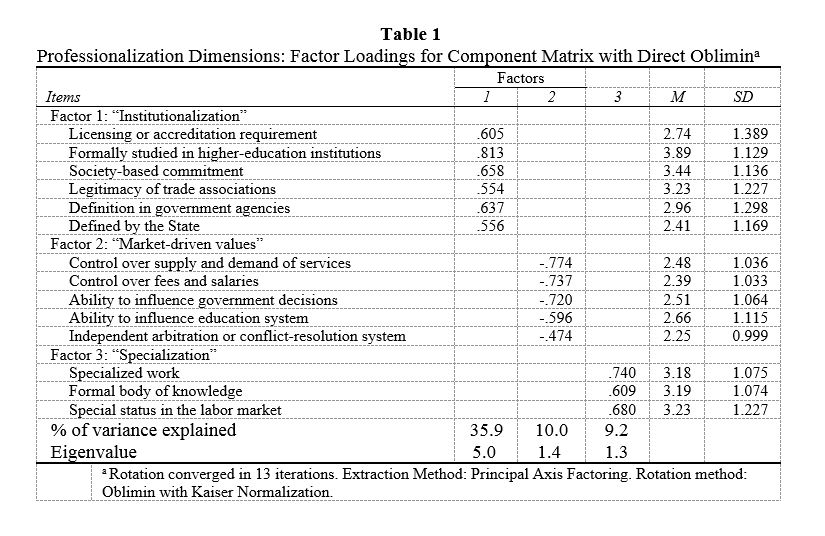

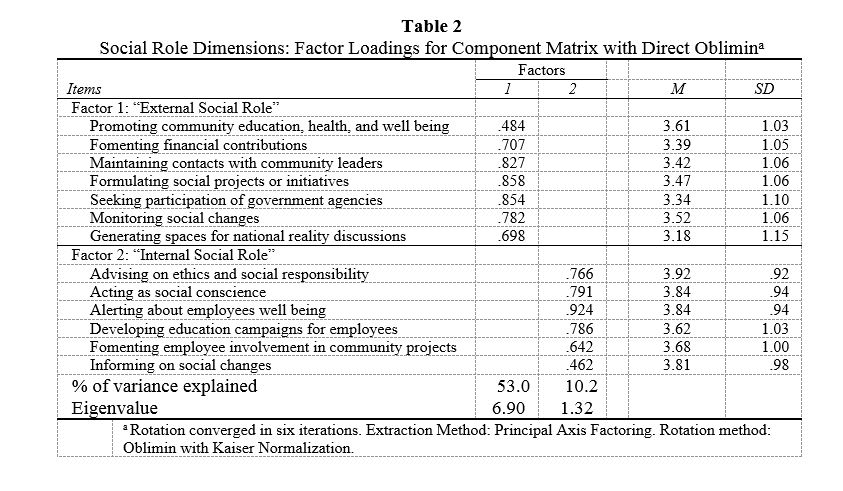

For the study, both the professionalization and social roles scales were submitted to principal axis factoring (PAF) with an Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization rotation to explore the pattern of responses among the multiple items included in the index. The direct oblimin rather than the varimax rotation was selected because there is a significant correlation between the factors, and the intent is to reproduce the actual results rather than force an independence that did not exist in the data. The screen plot method indicated that the three-factor solution for professionalization and two-factor solution for social roles (Table 2) was a reasonable interpretation of the data.

Measurement Instrumentation

The three-factor solution of professionalization (Table 1) highlights three main dimensions of professionalization as institutionalization, market-driven values, and specialization. The first factor for the 14 professionalization items is labeled Institutionalization. The means for these items varied from 2.41 to 3.89 on the five-point scale. The second factor is labeled Market-driven values. The two items with the strongest loadings (> .70) were control over supply and demand of services and control over fees and salaries. The third factor, labeled specialization, had loadings greater than .45. Overall this factor has higher mean scores than the factors named institutionalization and market-driven values.

For the social roles dimensions, the first seven statements dealt with external aspects that included: promoting community education, health, and well-being; fomenting financial contributions for the development of the community; maintaining contacts with community leaders; formulating social projects or initiatives to meet government and political expectations; seeking participation of government agencies; monitoring social changes to identify opportunities; and generating spaces for discussions on the national reality. The second six statements dealt with internal aspects, such as advising on ethics and social responsibility, acting as part of the organization’s social conscience, alerting about the well-being of employees, developing education campaigns for employees, fomenting employee involvement in community projects, and informing the organization on social changes. The 13 statements were sequentially presented as a section of the online instrument. In the two-factor model of social roles of public relations professionals, the first factor represented 53 percent of the variance and the second 10.2 percent. The factor loadings for the pattern matrix and the means and standard deviations appear in Table 2.

Findings

To test the model of professionalization and social roles as presented in Fig. 1, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to explore the relationships between professionalization and social roles of professionals. In the tested model, institutionalization, market-driven values, specialization, internal social roles, and external social roles were specified as latent variables with multiple indicators. AMOS 20.0 was used as the statistical package for model estimation.

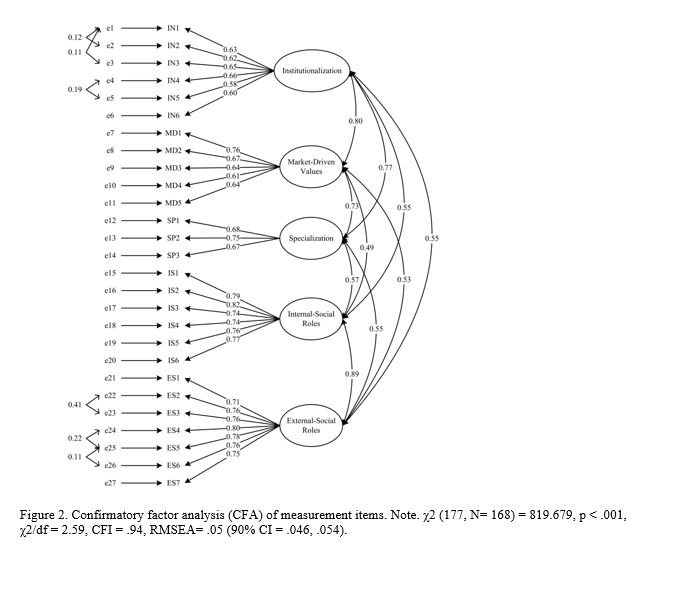

According to Byrne (2001) and Hu and Bentler (1999) a confirmatory factor model (and structural equation model) can be retained as a valid model when the value of χ2/df (as a parsimonious fit index) is less than three, the value of comparative fit index (CFI) is equal to or greater than .90 ideally, and the value of root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is equal to or less than .08.

Estimation for the initial measurement model indicated unsatisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (183, N= 168) = 545.80, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.98, CFI = .86, RMSEA= .11 (90% CI = .098, .120). Then we proceeded to modify the model. For the modification, we added error covariances among the observed items within the same subscale, following Byrne’s (2001) recommendation. The modified measurement model (see Fig. 2) was re- estimated and the results indicated a satisfactory fit, χ2 (177, N= 168) = 819.679, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.59, CFI = .94, RMSEA= .05 (90% CI = .046, .054).

Hypotheses Testing

Hypothesis 1(a) posited that institutionalization is positively associated with internal social roles of professionals. As the path H1(a) in Figure 3 indicates, this hypothesis was supported, β= .29 (B = .294, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This means that institutionalization is associated with the internal social roles of professionals. Hypothesis 1(b) theorized positive association between institutionalization and external social roles of professionals, β= .26 (B = .263, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This hypothesis was supported which substantiates that institutionalization is related with external social roles of public relations professionals.

Hypothesis 2 (a) on market-Driven values being positively associated with internal social roles of professionals, β= -.075 (B = -.074, S.E. = .41) was not supported reinforcing the social conscience “internal role” of a public relations practitioner. Hypothesis 2 (b) stated how market-Driven values is positively associated with external social roles of professionals, β= -.186 (B = -.186, S.E. = .41), p < .01. This hypothesis was supported which connects the factors of market-driven values of the profession and the external social roles a practitioner perform.

Hypothesis 3 (a) Specialization is positively associated with internal social roles of professionals, β= .22 (B = .230, S.E. = .38), p < .01 was supported extending the need for establishing a specialized body of knowledge for the profession and to regulate information and expertise within an organization. Hypothesis 3 (b) Specialization is positively associated with external social roles of professionals β= .17 (B = .178, S.E. = .38), p < .01 was also supported bringing together the external role capabilities and specialization aspect of the profession.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study conceptualized and tested a model of professionalization of public relations and the social roles that the professionals play in their organizations. This was possible by analyzing previous research and conceptualizing the proposed association with the work of public relations scholars who have advocated for social responsibilities of the professional. Responsibilities or roles supported by the evolution and maturity of the profession. The theoretical framework used to conceptualize and operationalize professionalization came from scholars of sociology of the professions.

In previous studies, measurements of professionalization and social roles were found to have high internal validity and consistency. However, the researchers, attending the feedback from reviewers of academic conferences and journals, decided to execute new factor analyses using direct oblimin rotation instead of varimax rotation. The results of the new analysis resulted in stronger factors of professionalization and social roles.

Confirmatory factor analysis, using structural equation modeling, resulted in a valid model. The model indicated that higher levels of professionalization (institutional, market-driven, and specialization) are positively related to the internal and external social roles of public relations professionals. That is, the greater the levels of the practice’s professionalization (institutional, market-driven, and specialization), the more enactment of professional roles for the betterment of internal and external stakeholders. This is significant in times when public relations has reached more relevance in all types of organizations with the potential of great impacts in organizations and societies worldwide.

Evidence of the dimensions or factors of professionalization and social roles and their interrelations are useful to fuel debates on the status of the professional and its professionals. Institutionalization includes the following indicators: accreditation, formal education, societal commitment, legitimacy of associations and trade groups, and the practice’s definition by governments and their agencies. The market-driven forces of the profession encompass control over supply, demand, fees, and salaries; ability to influence governmental and educational decisions that impact the practice and area of study; and independent arbitration or conflict-resolution system, which, according to participants’ views, needs significant improvement. Professional specialization includes the unique characteristics of public relations activities in the labor market and organizational/agency settings and the existence of a formal academic and trade body of knowledge.

Internal social roles of public relations professionals includes advising on ethics and social responsibility of organizations, acting as part of the social conscience of organizations and agencies, advising and developing campaigns and programs for the well-being of employees and their involvements as volunteers in community relations activities, and gathering and sharing information on social changes that may impact organizations and stakeholders. External social roles encompass promoting community education, public health, and betterment through the projects and initiatives; fomenting corporate donations and other financial contributions/philanthropy; maintaining communications with community leaders; partnering with government agencies in projects and community-outreach activities, monitoring external social change, and generating spaces for debate on political and economic issues of societies where organizations operate. This latter social roles’ indicator, according to participants, is not an integrate part of current professional responsibilities, especially in countries with challenging political and economic environments. The delicate balance organizations must keep when addressing public issues may have influenced this result; in general, organizations and agencies avoid being seen as actors and public opinion leaders with other motives than the betterment of the communities where they operate.

Theoretical Implications

Public relations is a modern occupation that has various levels of development in various locations all over the world. From its origin in the United States and Western Europe, it is advancing as a major profession in many other established and emergent markets. However, we are far from having a standardized practice and field of study. This study has carved a path of inquiry that offers new insights to the operationalization of professionalization of public relations and the social responsibility of the professionals. Hopefully, this will spark further interest on these topics and encourage additional testing of the two constructs and their intricate relationship. The individual scales measuring each constructs have obtained high internal validity and consistency, and the association between the three dimensions of professionalization and the two dimensions of social roles has been supported with statistically significant results.

Practical Implications

With the results of this study, the public relations professional community will have additional arguments to further advocate for the professionalization of the practice and field of study. The study of professionalization of public relations as a sector of the labor market instead of the professional characteristics of who practice this management function in organizations would allow trade associations and groups to keep in mind all the infrastructural and policy conditions needed to elevate the status of the practice and field of study. Specifically, results from this study could form the basis of professional training workshops and even create specific academic curricula for universities worldwide. These curricula can also involve active interactions and discussions with the professional members of trade associations and other leading institutions, such as foundations and think tanks of public relations.

One of the most important aspects of a legitimate profession is the commitment of its institutions and members to the influence of society. The association between professionalization and social roles of the professionals should be used as a basis to promote the social impact of public relations in an evolving global economic and political system.

Limitations and Future Research

The results of this study cannot be generalized to the practice of public relations and to the population of professionals in Latin America. In addition, the data for this analysis were gathered at the end of 2009. This study requires replication and, perhaps, a longitudinal investigation for generalizability. Additionally, this study focuses on 10 Latin American countries, it would be beneficial to extend this type of study to other regions of the world, including the United States of America. Finally, antecedents of professionalization and outcomes of the social roles of public relations professionals could also be studied in future research. Antecedents of professionalization may include economic indicators, traditional and emergent media infrastructure, and political freedoms; outcomes of the enactment of social roles may include effectiveness, leadership, and additional trust,respect, and loyalty for public relations work of among the organizations, clients, and stakeholders with whom professionals work.

REFERENCES

Beam, R. A. (1990). Journalism professionalization as an organizational-level concept: Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

Bendell, J. (2005). In whose name? The accountability of corporate social responsibility. Development in Practice, 15 (3&4), 362-374.

Bissland, J.H, & Rentner, T.L. (1989). Public relations’ quest for professionalization: An empirical study. Public Relations Review, 15(3), 53.

Bowen, S.A. (2007). Ethics and public relations. Institute for Public Relations’ website. Retrieved October 12, 20112, from https://instituteforpr.org/topics/ethics-and-public-relations/

Boynton, L. (2002). Professionalization and social responsibility: Foundations of public relations ethics. Communication Yearbook, 26, 230-265.

Broom, G.M. (1982). A comparison of sex roles in public relations. Public Relations Review, 8(3), 7–22.

Broom, G.M., & Dozier, D.M. (1986). Advancement for public relations role models. Public Relations Review, 12(1), 37–56.

Broom, G.M., & Smith, G. D. (1979). Testing the practitioner’s impact on clients. Public Relations Review, 5(3), 47–59.

Bronn, P.S. & Bronn, C. (2003). A reflective stakeholder approach: Co-orientation as a basis for communication and learning. Journal of Communication Management, 7(4), 291-303.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts. Applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Burns, E. (2007). Positioning a post-professional approach to studying professions. New Zealand Sociology, 22(1), 69-98.

Cameron, G. T., Sallot, L. M., & Lariscy, W. (1996). Developing standards of professional performance in public relations. Public Relations Review, 22(1), 43-61.

Chevron ordered to pay $8 billion by Ecuador court. (2011, February 14). Los Angeles Times’ website. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://articles.latimes.com/2011/feb/14/business/la-fi-chevron-20110214

Code of ethics. (2011). Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management’s website. Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.globalalliancepr.org/website/page/about-ga

Coleman, R., & Wilkins, L. (2009). The moral development of public relations professionals: A comparison with other professions and influences on higher quality ethical reasoning. Journal of Public Relations Research, 21(3), 318-340.

Coombs, W.T., Holladay, S., Hasenauer, G., & Signitzer, B. (1994). A comparative analysis of international public relations: Identification and interpretation of similarities and differences between professionalization in Austria, Norway, and the United States. Journal of Public Relations, 6(1), 23-39.

David, P. (2004). Extending symmetry: Toward a convergence of professionalization, practice, and pragmatics in Public Relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 16 (2), 185-211.

Dozier, D.M. (1992). The organizational roles of communications and public relations professionals. In J.E. Grunig, D.M. Dozier,W.P. Ehling, L.A. Grunig, F.R. Repper, & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in public relations and communication management (pp. 327–355). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dozier, D. M., & Broom, G. M. (1995). Evolution of the manager role in public relations practice. Journal of Public Relations Research, 7, 3–26.

Edelman, R. (2011, June 10). Retrieved on May 14, 2012 from http://www.prsa.org/SearchResults/view/9230/105/Richard_Edelman_on_the_future_of_public_relations

Environmental education for employees and their families. (2010). Panasonic’s website. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://panasonic.net/eco/communication/global/latin_america.html

Ferguson, M.A. (1981, August). Reliability and validity issues associated with the McLeod-Hawley index of professional orientation. Paper presented to the Theory and Methodology Division, Association for Education in Journalism annual convention, East Lansing, MI.

Fitzpatrick, K.R., & Gauthier, C. (2001). Toward a professional responsibility theory of public relations ethics. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 16(2-3), 193-212.

Fitzpatrick, K.R. (1996). The role of public relations in the institutionalization of ethics. Public Relations Review, 22(3), 249-258.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalization: The third logic. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Freidson, E. (1983). The theory of professions: State of the art. In R. Dingwall and O. Lewis (Eds.), The sociology of the profession: Lawyers, doctors and others (pp. 19-37). London: The Macmillan Press.

Gitter, A.G., & Jaspers, E. (1982). Are PR counselors trusted professionals? Public Relations Quarterly, 27, 28-31.

Global eco projects. (2010). Panasonic’s website. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://panasonic.net/eco/communication/global/latin_america.html

Grunig, J. E. (2000). Collectivism, collaboration, and societal corporatism as core professional values in public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12, 23–48.

Grunig, J. E., & Hunt, T. (1984). Managing Public Relations. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Grunig, J. E., & White, J. (1992). The effect of worldviews on public relations theory and practice. In J. E. Grunig, D. M. Dozier, W. P. Ehling, L. A. Grunig, F. R. Repper, & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in public relations and communication management (pp. 31–64). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hallahan, K.E. (1974). Professional association membership, professional socialization and the professional orientation of the public relations practitioner. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WS.

Hallahan, K. (2004). “Community” as a foundation for public relations theory and practice. Communication Yearbook, 28, 233-279.

Heath R. L. & L. Ni, (2008). Corporate social responsibility. Institute for Public Relations website, Retrieved October 12, 2011, from https://instituteforpr.org/topics/corporate-social-responsibility.

Holtzhausen, D.R. (2000). Postmodern values in public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12(1), 93-114.

Holtzhausen, D.R. (2002). Towards a postmodern research agenda for public relations. Public Relations Review, 28, 251-264.

Holtzhausen, D.R., & Voto, R. (2002). Resistance from margins: The postmodern public relations practitioner as organizational activist. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14(1), 57-84.

Hu & Bentler (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55.

Judd, L.R. (1989). Credibility, public relations and social responsibility. Public Relations Review, 15(2), 34-40.

Kim, S. and Reber, B. H. (2009). How public relations professionalization influences Corporate Social Responsibility: A survey of professionals. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 86(1), 157-174.

Krause, E. A. (1996). Death of the guilds: Professions, states, and the advance of capitalism, 1930 to the present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kruckeberg, D. (2000). The public relations practitioner’s role in practicing strategic ethics. Public Relations Quarterly, 45(3), 35–39.

Kruckeberg, D., & Starck, K. (1988). Public relations and community: A reconstructed theory. New York: Praeger.

Labor strikes slow Argentine oil output. (2011, May 14). Reuters’ website. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/05/14/argentina-oil-strike-idUSN1415523820110514

Lages, C. & Simkin, L. (2003). The dynamics of public relations: key constructs and the drive for professionalization at the practitioner, consultancy and industry levels. European Journal of Marketing, 37 (1/2), 298-328.

Lamme, M.O., & Russell, K.M. (2010). Removing the spin toward a new theory of public relations history. Journalism and Mass Communication Monographs, 11(4), 281-362.

Leeper, K. A. (1996). Public relations ethics and communitarianism: A preliminary investigation. Public Relations Review, 22(2), 163–179.

Leeper, R. (2001). In search of a metatheory for public relations; an argument for communitarianism. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), and G. Vasquez (Contributing Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 93–104). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

L’Etang, J. (1994). Public relations and corporate social responsibility: Some issues arising. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(2), 111–123. Livesey, S., Hartman, C., Stafford, E., Shearer, M. (2009). Performing sustainable development through eco-colaboration. Journal of Business Communication, 46(4), 423-454.

Lurati, F., & Eppler, M. (2006). Communication and management: Researching corporate communication and knowledge communication in organizational settings. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(2), 75-98.

McLeod, J.M., & Hawley, S.E., Jr. (1964). Professionalization among newsmen. Journalism Quarterly, 46, 529-539.

Molleda, Athaydes, & Suárez (2010). Latin American macro-survey of communication and public relations. Organicom, 7(13), 118-141.

Molleda, J.C., & Suárez, A.M. (2006). The roles of Colombian public relations professionals as agents of social transformation: how the country’s crisis forces professionals to go beyond communication with organizational publics. Glossa, 1(1), 15-34.

Molleda, J.C., & Ferguson, M.A. (2004). Public relations roles in Brazil: hierarchy eclipses gender differences. Journal of Public Relations Research, 16 (4), 327-351.

Molleda, J.C. (2002, August). International paradigms: the social role of the Brazilian public relations professionals. Paper presented at the 85th Annual Convention, Association of Journalism and Mass Communication, Miami, Florida.

Molleda, J.C. (2011). Comparative Quantitative Research on Social Roles in 10 Latin American Countries. Paper presented at the 2011 International Communication Association Conference, May 24-28, 2012, Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

Molleda, J.C. (2001). International paradigms: The Latin American school of public relations. Journalism Studies, 2(4), 513-530.

Molleda, J.C., & Moreno, A. (2008). Balancing public relations with socioeconomic and political environments in transition: comparative, contextualized research of Colombia, México and Venezuela. Journalism and Mass Communication Monographs, 10(2), 116-174.

Nayman, O. McKee, B.K. & Lattimore, D.L. (1977). PR personnel and print journalists: A comparison of professionalization. Journalism Quarterly, 54(3) 492-497.

Our mission, vision and values. (n.d.). Chattered Institute of Public Relations’ website. Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.cipr.co.uk/content/about-us/mission-vision-and-values

Outlook and policy issues for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2011). Regional economic outlook: Western hemisphere, International Monetary Fund (IMF). Retrieved October 20, 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2011/whd/eng/pdf/wreo1011c2.pdf.

Paluszek, J. (2007, May 28). Retrieved on May 12, 2012 from http://www.ketchum.com/speeches

Pieczka, M., & L’Etang, J. (2001). Public relations and the question of professionalization. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 223-235). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Read, J. (2011). Bolivia Amazon road dispute dents Evo Morales’ support. BBC News Website. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-15144719.

Rentner, T.L., & Bissland, J.H. (1990). Job satisfaction and its correlates among public relations workers. Journalism Quarterly, 67(4), 950-955.

Ryan, M. (1986). Public relations professionals’ views of corporate social responsibility. Journalism Quarterly, 63(4), 740-762.

Ryan, M., & Martison, D.L. (1990). Social science research, professionalization and public relations professionals. Journalism Quarterly, 67(2), 377-390.

Skinner, C., Mersham, G., & Valin, J., (2004). Global protocol on ethics in public relations. Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.teid.org.tr/files/downloads/kutuphane/dunyadan/global_protocol_on_ethics_in_public_relations.pdf

Starck, K., & Kruckeberg, D. (2003). Ethical obligations of public relations in an era of globalization. Journal of Communication Management, 8(1), 29-40.

Starck, K., & Kruckeberg, D. (2001). Public relations and community: A reconstructed theory revised. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), and G. Vasquez (Contributing Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 51–59). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Toth, E.L., Serini, S.A., Wright, D.K., & Emig, A.G. (1998). Trends in public relations roles: 1990–1995. Public Relations Review, 24(2), 145–163.

van Ruler, B. (2005). Commentary: Professionals are from Venus, Scholars are from Mars.” Public Relations Review, 31, 159-173

van Ruler, B. & Verčič, D. (2004). Public relations and communication management in Europe. Berlin, Germany: Mounton de Gruyter.

Verčič, D., van Ruler, B., Bütschi, G., & Flodin, B. (2001). On the definition of public relations: A European view. Public Relations Review, 27(4), 373-387.

Verčič and J. Grunig (2000). The origins of public relations theory in economics and strategic management. In D. Moss, D. Vercic, & G. Warnaby, Perspectives on Public Relations Research (pp. 7-58). London and New York: Routledge.

Vision, mission & values. (2011). Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management’s website. Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.globalalliancepr.org/website/page/about-ga.

Visser, W. (2007), Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries. Retrieved from http://www.waynevisser.com/chapter_wvisser_csr_dev_countries.pdf

Weis, D., & Schank, M.J. (1997). Toward building an international consensus in professional values. Nursing Education Today, 17(5), 366-369.

White, J. (2011, December 7). Retrieved on June 10, 2012 from http://www.cipr.co.uk/sites/default/files/PR%202020%20Final%20Report_0.pdf

Wright, D. (1979). Professionalization and social responsibility in public relations. Public Relations Review, 5(3), 20-33.

Wright, D. K. (2011). Social responsibility in public relations: A multi-step theory. Science Direct. Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0363811176800318

Yeates, R. (2002). Public skepticism and the ‘social conscience’: New implications for public relations . Deakin Journal, 4(1). Retrieved October 12, 2011, from http://www.deakin.edu.au/arts-ed/apprj/vol4no1.php?print_friendly=true

Zerfass, A. (2008). Corporate communication revisited: Integrating business strategy and strategic communication. In A. Zerfass, B. van Ruler, & K. Sriramesh (Eds.), Public relations research: European and international perspectives and innovations (pp. 65-96). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.