This blog is based on the original study in the Public Relations Journal.

When we need expertise in life or business situations, we often look to experts for help. For example, when a crisis strikes (and even before), executives seek out communication leaders for advice on how to navigate tricky situations. But what does such terminology mean? What qualifications differentiate certain lines of work as a profession? Are those who work in organizational or institutional communication professionals? Does our field of work qualify as a profession?

The history of professions goes back at least as far as the Greek and Roman empires. This distinction was given to vocations that relied on distinct education. The traditional professions, including law, medicine, and the clergy, came into such recognition during the medieval period. Such distinction required that members complete a rigorous education in the liberal arts, and a period of apprenticeship. Those who entered professions held an elite status in society. Their work communities stood apart as separate and distinct from other forms of labor. The professions as we know them today are a product of the industrial age, during which time bodies such as the American Medical Association and American Bar Association came into being, establishing forms of governance and licensing over their member practitioners.

Most literature speaks of the idea of a profession broadly, so finding an accurate definition is difficult. Webster’s Dictionary defines a profession as “the body of qualified persons of a specific occupation or field.” Yet, this is an over-simplification. At the heart of the matter, the purpose of professions is to connect work to a higher purpose. In that spirit, I define a profession as a “community of specially skilled practitioners who devote themselves to vocational practices that contribute to human flourishing.” These practices are marked by honesty, excellence, and personal commitment to the craft, the public, and fellow members of the profession. That said, most scholars view the professions according to attributes.

There are several attributes that categorize professions. Predominant indicators include offering a public service, controlling access to the vocation, instilling specialty skills, and requiring members to practice ethically. Do those of us who work as communicators measure up? As a military public affairs officer, I explored this question in a recent study published in the Public Relations Journal.

I surveyed indicators most frequently associated with professions and organized them by 10 basic attributes. Accordingly, professions:

1.) Operate with a high degree of autonomy: Professions enjoy a wide leeway of operation with minimal supervision and high deference from officials outside their respective areas of expertise.

2.) Self-police to a vocational code of ethics: To enjoy a high degree of autonomy, professions agree to police members internally through codes of ethics and means of sanction for practitioners who depart from established ethical guidelines that are established by their peers in the vocational community.

3.) Promulgate a sense of corporateness across the community of practitioners: Professions create and maintain associations that promote expertise and a sense of community among those who practice the craft.

4.) Provide an essential public service to society: Professions offer services that are perceived to be an essential part of proper societal function.

5.) Comprise members who consider membership in the profession to be a life-long calling: This attribute holds that members of professions commit to them long term, and identify with developing expertise in their chosen fields as a personal value.

6.) Uphold standards through ongoing development of member practitioners: Professions inspire excellence in vocational practices by facilitating ongoing training, as well as facilitating certification and informational events to enhance the professional body’s ability to better serve the public.

7.) Are full-time, non-manual occupations: This kind of work is more cognitive than physical. As such, it does not require high levels of physical exertion and is typically performed in an office setting.

8.) Grant access to the field of work through certification: Professions require a formalized and advanced training regimen that members must complete in order to gain entry and be allowed to practice.

9.) Operate according to a body of theory: Work associated with a profession must be grounded in unique knowledge that is specific to a unique form of vocational practice.

10.) Acknowledged by the public as fulfilling the requirements of a profession: Professions are granted this standing by the public as a confirmation of trust.

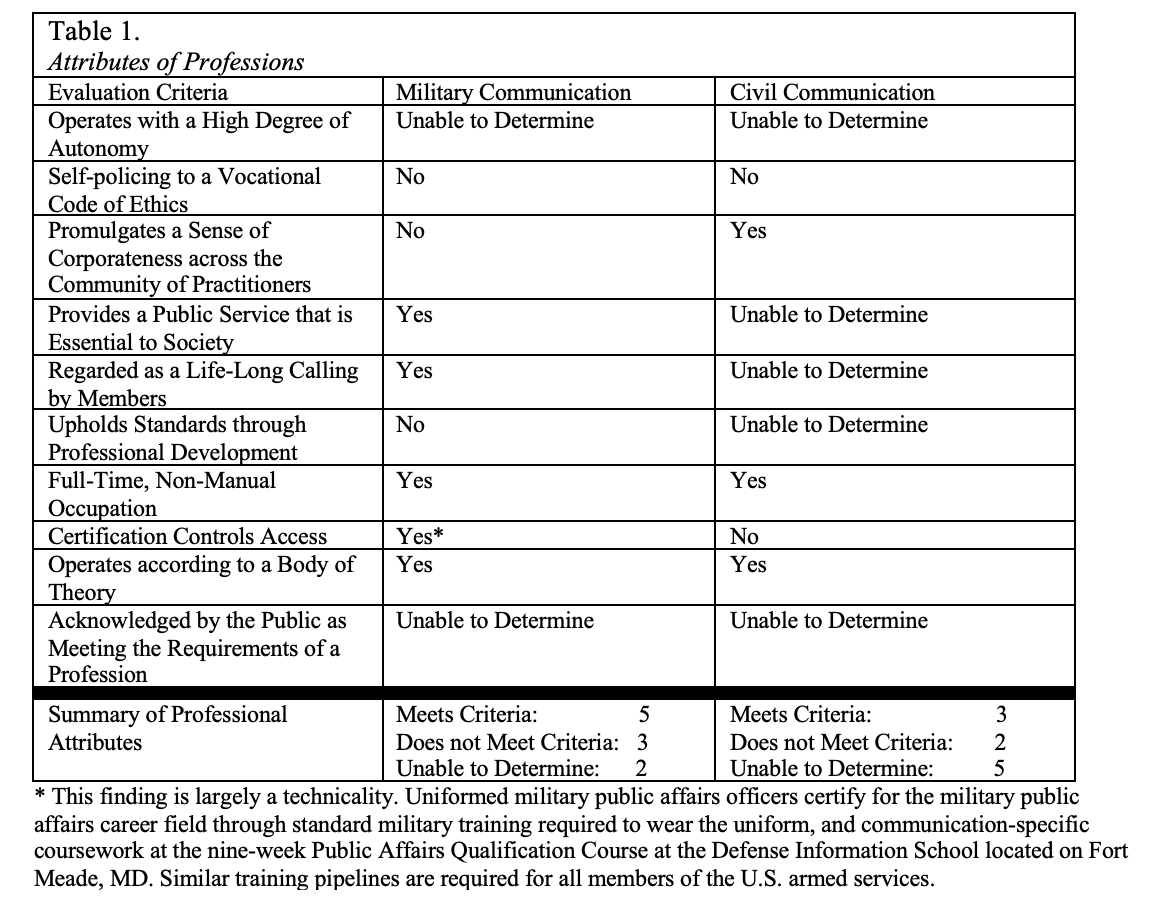

With these attributes ascertained from many others who have written on the topic, I segmented them by military communicators and civil communicators based on my experience in both sectors. Then, I analyzed where communicators stack up (see Table 1: Attributes of Professions).

Findings suggest that we are not as close to the mark as we might like to think. While those of us who work as organizational communicators bring expertise to our labors, communicators are not quite there when it comes to the traditional attributes used to identify professions.

I want to highlight one area that stands out as the most likely attribute where both the fields of civil and military communication most clearly miss the mark. Though both have established codes of ethics, neither enforce them on practitioners through formal means. To the contrary, ample documentation exists to demonstrate that some among the public relations and public affairs communities are content to practice unethically and dishonestly. If that is not addressed, it matters little what other attributes we might seek to meet in earning the trust required to enable standing among the professions.

This topic matters because those of us who work in communication on behalf of others can play a role in building or breaking societal trust. Even the long-standing professions are not safe. Unethical practices among business, government, medicine, law, and media are causing fissures of trust that may be irreparable. Societies without trust become societies that fail. The consequence of such an outcome risks an existential threat to our inherited experiment in ordered liberty.

This is not a topic of mere semantics, but how practitioners set the culture, perception, and relevance of the work to which they commit a great percentage of lifetime and energy to accomplishing. Communicators hold the tools to fracture or to build bridges between individual stakeholders, groups, and societies. Those who endeavor to serve society well through the application of their vocational talents are more likely to understand and appreciate the weight and responsibility of their role in representative society than those who do not. While our closely-related fields of communication may not equate to the grade of profession, we are not absolved of the responsibility to steward them with an eye toward preserving trust here and now, and setting better conditions for those who will one day take up the mantle we carry now. Let us be practitioners who take the field to the next level by seeking not only to work well, but to serve well, too.

Chase Spears has served as a military public affairs officer for 20 years and concluded his military duties as a public affairs training advisor. He currently serves as a U.S. Army Career Skills Program fellow at the Kansas State House of Representatives. Chase is a Ph.D. candidate in at Kansas State University, and teaches crisis communication as an adjunct professor for Spurgeon College in Kansas City, Missouri. You can connect with him on LinkedIn.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not representative of the official views or policies of the U.S. Army, U.S. Defense Department, nor any other agency or entity public or private.