This is an updated version of Crisis Management and Communications by Dr. W. Timothy Coombs. The original version can be found here.

Download Accompanying Infographics:

Crisis Comms Infographic 1 Revised 2020

Crisis-Comms Infographic 2 Revised 2020

Introduction

It was important to update the crisis communication entry for two reasons. One, there has been a significant amount of new research since the original entry was created. This new research provides support for some existing crisis communication knowledge as well as generating some novel insights. Second, the emergence of social media channels demands that they be integrated into the crisis management and communication process. This entry retains most of the original findings because the advice and insights are still valid. The “new” insights and advice derived from more recent crisis communication research have been integrated into the existing material.

As in the original piece, I am reviewing and synthesizing research that examined organizational crises. It is important to note in this revision the shifting nature of organizational crises. Historically, organizational crises have been considered a threat to the operations of an organization. An explosion could cripple production, a defective product would create the need for a recall and lost product, and a massive snow storm can disturb the flight operations of airlines. Crises also have a reputational element. A crisis does inflict harm on the organization’s reputation because of the negative information it generates about the organization (Barton, 2001). Today, it is appropriate to create the categories of operational crises and reputational crises (Sohn & Lariscy, 2014). Again, a crisis can affect both but one of the two factors can dominate a crisis.

Key Concepts

There are plenty of definitions for a crisis. For this entry, the definition reflects key points found in the various discussions of what constitutes a crisis. A crisis is defined here as a significant threat to operations or reputations that can have negative consequences if not handled properly. In crisis management, the threat is the potential damage a crisis can inflict on an organization, its stakeholders, and an industry. A crisis can create three related threats: (1) public safety, (2) financial loss, and (3) reputation loss. Some crises, such as industrial accidents and product harm, can result in injuries and even loss of lives. Crises can cause financial loss by disrupting operations, creating a loss of market share/purchase intentions, or spawning lawsuits related to the crisis. As Dilenschneider (2000) noted in The Corporate Communications Bible, all crises threaten to tarnish an organization’s reputation. A crisis reflects poorly on an organization and will damage a reputation to some degree. Moreover, experts now recognize the existence of reputation-based crises (e.g., Sohn & Lariscy, 2014). Clearly these three threats are interrelated. Injuries or deaths will result in financial and reputation loss while reputations have a financial impact on organizations.

Effective crisis management handles the threats sequentially. The primary concern in a crisis has to be public safety. A failure to address public safety intensifies the damage from a crisis. Reputation and financial concerns are considered after public safety has been remedied. Ultimately, crisis management is designed to protect an organization and its stakeholders from threats and/or reduce the impact felt by threats.

Crisis management is a process designed to prevent or lessen the damage a crisis can inflict on an organization and its stakeholders. As a process, crisis management is not just one thing. Crisis management can be divided into three phases: (1) pre-crisis, (2) crisis response, and (3) post-crisis. The pre-crisis phase is concerned with prevention and preparation. The crisis response phase is when management must actually respond to a crisis. The post-crisis phase looks for ways to better prepare for the next crisis and fulfills commitments made during the crisis phase including follow-up information.

The term social media crisis has been used to describe crises that emerged in or were amplified by social media. However, the term social media crisis is just too vague and includes situations that were not traditional crises. For instance, most of the social media crises documented in #Fail: The 50 Greatest Social Media Screw-Ups and How to Avoid Being the Next One were actually customer service problems. Most organizations are not going to assemble the crisis management team to address a customer service problem even if that problem is trending on Twitter and getting hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube. Paracrisis is a more precise term for the way social media is influencing the emergence of a crisis. A paracrisis is a situation where managers must address a crisis risk in full view of its stakeholders (Coombs & Holladay, 2012). Essentially the pre-crisis phase moves from private to public view. If a paracrisis is mishandled—there is ineffective crisis communication—it can escalate into a crisis. Social media has had a significant effect on altering the pre-crisis phase of crisis communication. Research has just begun to explore those changes.

At this point it is important to clarify the general connection between social media and crisis communication. Social media represents a variety on Internet channels that allow stakeholders to create content (Coombs & Holladay, 2012). Social media allow any individual with Internet access to post their ideas and images for others to see. Social media enters the revised entry is two ways. First, it is important to discuss the general relationship between social media and crisis communication. Second, the research and advice concerning social media’s role in crisis communication is integrated into the discussion of the three crisis phases. I would like to begin this general discussion of social media and crisis communication by debunking two crisis communication myths that have emerged along with social media:

Myth 1. What we knew about crisis communication should be forgotten because it is no longer valid.

Myth 2. Strategy is no longer relevant to crisis communication; it is all about reaction speed and tactics now.

For myth one, social media has created the need to modify crisis communication but the old crisis communication knowledge base remains viable. The basic elements of crisis communication are not changing. What is changing is the way we execute many of those basic elements. For instance, crisis managers have always used scanning. Social media add new sources that must be part of the crisis scanning process. Another change has been the addition of social media managers to the crisis management team (Coombs, 2015; González-Herrero & Smith, 2008). For myth two I would say that strategy never goes out of style. Speed does not trump the need to pursue a specific outcome and developing messages to achieve that outcome—to be strategic. There is no doubt that managers are under pressure to react even more quickly in crises with the advent of the Internet. However, managers must be deliberate and make informed decisions because they have responsibilities to a range of stakeholders. Speed is enhanced by crisis preparation. Crisis preparation allows crisis managers to be both fast and deliberate. Researchers are trying to understand how crisis communication can make the best use of social media and to debunk the myths social media has created for crisis communication.

The tri-part view of crisis management identified earlier serves as the primary organizing framework for this entry. However, the revised entry has new a section that reviews some lines of crisis communication that increased in prominence over the past few years and offer useful advice for practitioners.

Emerging Crisis Communication Research Lines

In a change from the original entry, it is helpful to present two crisis communication research lines that have been very important since the writing of the original entry. Those crisis communication research lines are internal crisis communication and stealing thunder.

Internal Crisis Communication

There is a growing interest in the internal aspect of crisis communication with a focus on how management communicates with employees about a crisis. Internal crisis communication is important because it helps to mitigate the stress crises produce for employees and to illuminate how employees can become ambassadors (an asset) during a crisis (Frandsen & Johansen, 2011). In general, the internal crisis communication research has found managers neglect communication with employees during a crisis. For instance, Johansen, Aggerholm & Frandsen (2012) found that 67% of Danish organizations had explicit policies for external crisis communication while only 31% had similar polices for internal audiences. Only 40% of organizations thought employees could be external ambassadors during a crisis while 47% thought employees could be effective internal ambassadors (Johansen et al., 2012). The conclusion was that organizations were not maximizing the utility of employees for crisis communication. The Danish researchers argue for a “communication model where employees are viewed not as passive receivers but also as active participants who take their own communicative initiatives trying to make sense of crisis situations; and who to a certain extent can be mobilized communicatively by the organization in crisis” (Johansen et al., 2012, p. 273).

Research in Italy illustrated the underuse and the value of internal crisis communication. Surveys and interviews with managers and employees found that managers felt they have been effective at crisis communication with employees while employees felt the crisis information was of poorly quality and were negative toward the internal crisis communication they experienced (Mazzei & Ravazzani, 2011). Additional research found that Italian managers relied heavily on evasion of responsibility and showed a general underestimation of the value of internal communication during a crisis. Managers generally failed to communicate corrective actions and accommodative actions to employees. Interestingly, that is the exact information employees wanted and needed. If employees are to face a crisis positively, the employees require information about actions the organization was taking to address the crisis—corrective and accommodative actions (Mazzei & Ravazzani, 2014).

A case analysis of an industrial accident at an Italian organization revealed the value of effective internal crisis communication. After a fatal accident, the employees were mostly positive toward the organization in their communication with very little negative communication. The positive employee reaction was attributed to the organization’s internal crisis communication efforts before and during the crisis. Prior to the crisis, managers had promoted the organization’s investment in safety—pre-crisis there was a risk communication effort relevant to the crisis. During the crisis, managers used the Intranet to clarify the company’s position, to remember the workers, and to reinforce the organization’s commitment to safety (Mazzei, Kim & Dell’Oro, 2012). While more research is needed, it appears that effective crisis communication must include internal communication efforts to keep employees properly informed and to convert them into ambassadors for the organization. Employees are an important asset and communication channel that too many organizations squander during a crisis.

Stealing Thunder

Stealing thunder is a concept crisis communication researchers have imported from law. In law, attorneys steal thunder by identifying a flaw in their own case before their opposition states the weakness (Williams, Bourgeois & Croyle, 1993). In a crisis, research consistently demonstrates that a crisis does less reputational damage if the organization is the first to report the crisis. The same exact crisis does less damage when the organization first reports it than when the news media or another source is the first to report the crisis (Arpan & Pompper, 2003; Claeys & Cauberghe, 2012). Stealing thunder is a matter of timing involving the disclosure of information about a crisis. As researchers note, stealing thunder is counterintuitive. Managers think it is better not to disclose a possible crisis because you do not disclose negative information if you do not have to because there is a chance others may never learn about the problem if the organization does not report it. Not reporting a crisis is dangerous. When organizations do not disclose problems them know exists, it creates the impression they do not care about the safety of their stakeholders. Consider how upset stakeholders were when they discovered GM management knew there was an ignition switch problem but did not disclose that to customers or the government.

Stealing thunder demonstrates the value of crisis communication timing for reputations. An interesting study compared the effect of timing (stealing thunder) and crisis response strategies. The research wanted to determine which of the two factors had a stronger effect on organizational reputations or if the two could be combined to increase the reputational protection value of crisis communication. The study compared situations whether or not an organization engaged in stealing thunder and if the crisis response was recommended by Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) or violated the SCCT recommendations. The results found that if the organization stole thunder, the type of crisis response had no effect on reputation. It seemed that stealing thunder provided all the reputational protection the organization could gain from crisis communication. However, when there was no stealing thunder, the recommended crisis response strategies were better at protecting reputations than the non-recommended crisis response strategies (Claeys & Cauberghe, 2012). The study shows just how powerful stealing thunder is as a crisis communication resource.

One interesting but tentative line of crisis communication research related to stealing thunder examines a channel effect for social media. A channel effect is when people react differently to the same message when it is delivered through different channels. The channel itself is shown to alter how people perceived and react to messages. Some researchers have argued that social media can have a channel effect for crisis communication (Schultz, Utz & Goritz, 2011; Utz, Schultz & Gloka, 2013). These studies suggest that some crises messages are perceived differently delivered via social media verses traditional news media. However, the pattern of the results is consistent with stealing thunder as well. Because stealing thunders can also explain the research results, I have labeled the channel effects for social media as tentative, in need of additional study, and part of stealing thunder. The channel studies do reinforce the value of organizations using social media as part of the mix of channels used to deliver a crisis response.

Pre-Crisis Phase

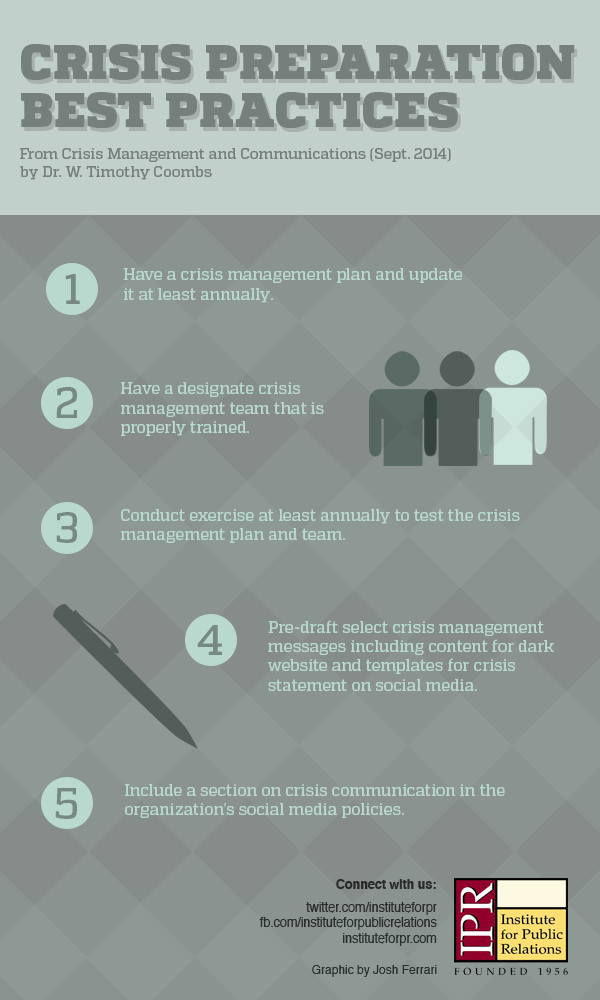

Prevention involves are designed to reduce known risks that could lead to a crisis. This is part of an organization’s risk management program. Preparation involves creating the crisis management plan, selecting and training the crisis management team, and conducting exercises to test the crisis management plan and crisis management team. Both Barton (2001) and Coombs (2006) document that organizations are better able to handle crises when they (1) have a crisis management plan that is updated at least annually, (2) have a designated crisis management team, (3) conduct exercises to test the plans and teams at least annually, and (4) pre-draft some crisis messages. Table 1 lists the Crisis Preparation Best Practices. The planning and preparation allow crisis teams to react faster and to make more effective decisions. Refer to Barton’s (2001) Crisis in Organizations II or Coombs’ (2006) Code Red in the Boardroom for more information on these four lessons.

Table 1: Crisis Preparation Best Practices

Crisis Management Plan

A crisis management plan (CMP) is a reference tool, not a blueprint. A CMP provides lists of key contact information, reminders of what typically should be done in a crisis, and forms to be used to document the crisis response. A CMP is not a step-by-step guide to how to manage a crisis. Lerbinger (2012), Coombs (2015), and Low, Chung and Pang (2012) have noted how a CMP saves time during a crisis by pre-assigning some tasks, pre-collecting some information, and serving as a reference source. Pre-assigning tasks presumes there is a designated crisis team. The team members should know what tasks and responsibilities they have during a crisis.

Crisis Management Team

Barton (2001) identifies the common members of the crisis team as public relations, legal, security, operations, finance, and human resources. We should now amend the list of common members to include the social media manager. Social media are used to deliver crisis messages, thus, the social media managers should be part of the crisis team. Organizations are criticized if their social media messages seem to ignore a crisis because there is an inconsistency in the messaging appearing in the different communication channels the organization is using. However, the composition of the crisis team will vary based on the nature of the crisis. For instance, information technology would be required if the crisis involved the computer system but not if involved product harm. Time can be saved when the team has already decided on who will do the basic tasks required in a crisis. Bernstein (2011) notes that plans are an “exercise in futility” if there is no crisis team training (p. 31). Management does not know if or how well an untested crisis management plan with work or if the crisis team can perform to expectations. Mitroff, Harrington, and Gia (1996) emphasize that training is needed so that team members can practice making decisions in a crisis situation. Research by Low et al. (2012) reinforces this claim by establishing how training improves the effectiveness of crisis team decision making. As noted earlier, a CMP serves only as a rough guide. Each crisis is unique demanding that crisis teams make decisions. Coombs (2015) summaries the research and shows how practice does improve a crisis team’s decision making and related task performance. For additional information on the value of teams and exercises refer to Bernstein (2011) and Coombs (2015).

Spokesperson

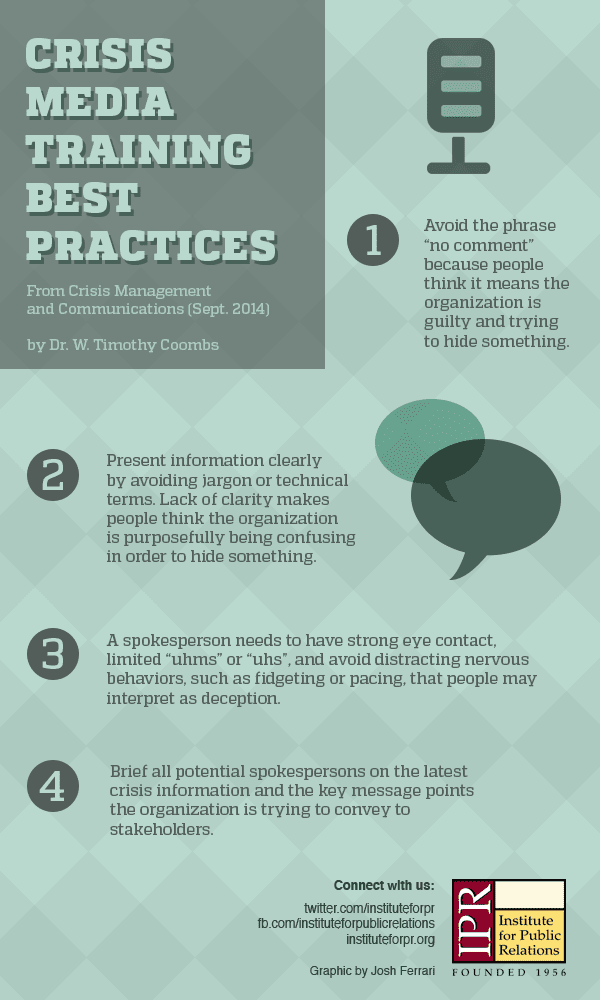

A key component of crisis team training is spokesperson training. Organizational members must be prepared to talk to the news media during a crisis. Much of the early writing on crisis communication involved media training and the topic remains relevant today. Lerbinger (2012), Barton (2001), Bernstein (2011) and Coombs (2015) devote considerable attention to media relations in a crisis. Media training should be provided before a crisis hits. The Crisis Media Training Best Practices in Table 2 were drawn from these three books:

Table 2: Crisis Media Training Best Practices

Public relations can play a critical role in preparing spokespersons for handling questions from the news media. The media relations element of public relations is a highly valued skill in crisis management. The public relations personnel can provide training and support because in most cases they are not the spokesperson during the crisis.

These media relations skills can be critical even in social media. The management video apology (frequently the CEO) posted online is a popular tool used in crisis communication. Domino’s posted a CEO video apology during its food tampering crisis (Veil, Sellnow & Petrun, 2012). An excellent example of an online CEO video apology is Maple Leaf Foods CEO Michael McCain in response to a deadly Listeria product harm crisis in 2008. (Here is link to the video). The same presentational advice holds for online videos. If you read the response to the Domino’s Pizza CEO’s apology, a large number of people are critical of his delivery and seemed to miss the message he is presenting.

Pre-draft Messages

Finally, crisis managers can pre-draft messages that will be used during a crisis. More accurately, crisis managers create templates for crisis messages. Templates include statements by top management, news releases, social media messages (e.g., Tweets, blogs, or Facebook posts) and dark web sites. Both the Corporate Leadership Council (2003) and the Business Roundtable (2002) were early proponents of using templates. The templates leave blank spots where key information is inserted once it is known. Public relations personnel can help to draft these messages. The legal department can then pre-approve the use of the messages. Time is saved during a crisis as specific information is simply inserted and messages sent and/or made available on a web site or through social media. Pre-drafting messages serves to save time. Instead of drafting and seeking approval of a message when a crisis hits, the crisis team simply adds relevant information and delivers the pre-written and approved messages (Coombs, 2015).

Communication Channels

An organization may create a separate web site for the crisis or designate a section of its current web site for the crisis. Experts typically prefer using the existing web site because a new web site might be difficult for stakeholders to find (Coombs, 2015). Taylor and Kent’s (2007) research finds that having a crisis web sites is a best practice for using an Internet during a crisis. The site should be designed prior to the crisis—a dark site is created before a crisis. This requires the crisis team to anticipate the types of crises an organization will face and the types of information needed for the web site. For instances, any organization that makes consumer goods is likely to have a product harm crisis that will require a recall. The Corporate Leadership Council (2003) highlights the value of a crisis web site designed to help people identify if their product is part of the recall and how the recall will be handled. Stakeholders, including the news media, will turn to the Internet during a crisis. Crisis managers should utilize some form of web-based response or risk appearing to be ineffective. A good example is Taco Bell’s E. coli outbreak in 2006. The company was criticized in the media for being slow to place crisis-related information on its web site.

It is safe to extend the insights from web sites to social media. Managers should use of social media to communicate about a crisis should be best practices. As noted earlier, the crisis messaging appears inconsistent if the crisis is only discussed in select Internet channels. Carnival Cruise Lines was criticized for not providing much information about the Costa Concordia tragedy in its social media communication during the crisis.

Of course not placing information on the web site or in social media messages can be strategic. An organization may not want to publicize the crisis by placing crisis information on their online channels. This assumes the crisis is very small and that stakeholders are unlikely to hear about it from another source. In today’s traditional and online media environment, that is a misguided if not dangerous assumption. A web site and social media offer another means for an organization to present its side of the story and not using it creates a risk of losing control over how the crisis story is told. One point of disagree among crisis experts is whether or not to start using a new social media channel during a crisis. Experts lean toward not using a new social media channel during a crisis because there is no history of a presence in that channel and little awareness the organization is now using that channel. American Airlines quickly stopped using a blog it created to help address a crisis because the traffic to the site was so low (Coombs, 2015). The counter argument is an organization needs to be where the crisis is unfolding. If the crisis breaks on Twitter, the organization must post a response on Twitter even if it has to create a Twitter account to accomplish that task.

The Social-Mediated Crisis Communication Model (SMCC) argues that social media channels have three different types of publics: (1). influential social media creators, they create crisis information for other stakeholders to consume, (2). social media followers, ones who “consume” messages from the influential social media creator, and (3). social media inactives, get the information from work-of-mouth with social media followers and/or tradition medial that report the content from influential social media creators. Crisis communicators should consider the value of these various publics when utilizing social channels in the crisis communication response (Liu, Austin & Jin , 2011; Liu, Jin & Austin, 2013).

Intranet sites can also be used during a crisis. Intranet sites limit access, typically to employees only though some will include suppliers and customers. Intranet sites provide direct access to specific stakeholders so long as those stakeholders have access to the Intranet. Downing’s (2003) research documents the value of American Airlines’ use of its Intranet system as an effective way to communicate with its employees following the 9/11 tragedy. Coombs (2015) notes that the communication value of an Intranet site is increased when used in conjunction with mass notification systems designed to reach employees and other key stakeholders. Many organizations are using enterprise social networking as Intranet sites. These are private social networking tools for employees while some organizations add suppliers and/or clients to the system. Enterprise social networking, a term that is replacing Intranet, is an idea channel for keeping employees and other stakeholders on the system informed about the crisis.

With a mass notification system, contact information (phones numbers, e-mail, etc.) are programmed in prior to a crisis. Contacts can be any group that can be affected by the crisis including employees, customers, and community members living near a facility. Crisis managers can enter short messages into the system then tell the mass notification system who should receive which messages and which channel or channels to use for the delivery. The mass notification system provides a mechanism for people to respond to messages as well. The response feature is critical when crisis managers want to verify that the target has received the message. Table 3 summarizes the Crisis Communication Channel Preparation Best Practices.

Table 3: Crisis Communication Channel Preparation Best Practices

- Be prepared to use part of your current web site to address crisis concerns.

- Be prepared to use the Intranet or enterprise social networking as one of the channels for reaching employees and any other stakeholders than may have access to your system.

- Be prepared to utilize a mass notification system for reaching employees and other key stakeholders during a crisis.

- Be prepared to utilize your existing social media channels for responding to your crisis.

Crisis Response

The crisis response is what management does and says after the crisis hits. Public relations plays a critical role in the crisis response by helping to develop the messages that are sent to various publics. A great deal of research has examined the crisis response. That research has been divided into two sections: (1) the initial crisis response and (2) reputation repair and behavioral intentions.

Initial Response

Practitioner experience and academic research have combined to create a clear set of guidelines for how to respond once a crisis hits. The initial crisis response guidelines focus on three points: (1) be quick, (2) be accurate, and (3) be consistent.

Be quick seems rather simple, provide a response in the first hour after the crisis occurs. That puts a great deal of pressure on crisis managers to have a message ready in a short period of time. Again, we can appreciate the value of preparation and templates. The rationale behind being quick is the need for the organization to tell its side of the story. In reality, the organization’s side of the story is a key point management wants to convey about the crisis to its stakeholders. When a crisis occurs, people want to know what happened. Crisis experts often talk of an information vacuum being created by a crisis. The news media will lead the charge to fill the information vacuum and be a key source of initial crisis information. (We will consider shortly the use of the Internet as well). If the organization having the crisis does not speak to the news media, other people will be happy to talk to the media. These people may have inaccurate information or may try to use the crisis as an opportunity to attack the organization. As a result, crisis managers must have a quick response. The advent of social media has only increased the pressure for a quick response (Coombs, 2015). An early response may not have much “new” information about the crisis but the organization positions itself as a source and begins to present its side of the story. Again, pre-drafted messages facilitate a quick response. Lerbinger (2012) reinforces the importance of speed with this quotation from Karen Doyne, crisis and issues management manager from Burson Marsteller, “One of the major yardsticks in crisis communications is meeting public expectations. And public expectations are rising all the time, particularly because of technology. First it was the 24-hour news networks. Then it was the Internet. An now, people demand information immediately and on a continual basis” (p. 46). Hearit’s (1994) research illustrates how silence is too passive. It lets others control the story and suggests the organization has yet to gain control of the situation. The stealing thunder research demonstrates how a quick, early response allows an organization to generate greater credibility than a slow response (Claeys & Cauberghe, 2012). Crisis preparation will make it easier for crisis managers to respond quickly.

Obviously accuracy is important anytime an organization communicates with publics. People want accurate information about what happened and how that event might affect them. Because of the time pressure in a crisis, there is a risk of inaccurate information. If mistakes are made, they must be corrected. However, inaccuracies make an organization look inconsistent. Incorrect statements must be corrected making an organization appear to be incompetent. The philosophy of speaking with one voice in a crisis is a way to maintain accuracy.

Speaking with one voice does not mean only one person speaks for the organization for the duration of the crisis. As Barton (2001) notes, it is physically impossible to expect one person to speak for an organization if a crisis lasts for over a day. Watch news coverage of a crisis and you most likely will see multiple people speak. The news media want to ask questions of experts so they may need to talk to a person in operations or one from security. That is why Coombs (2015) emphasizes the public relations department plays more of a support role rather than being “the” crisis spokespersons. The crisis team needs to share information so that different people can still convey a consistent message. The spokespersons should be briefed on the same information and the key points the organization is trying to convey in the messages. The public relations department should be instrumental in preparing the spokespersons. Ideally, potential spokespersons are trained and practice media relations skills prior to any crisis. The focus during a crisis then should be on the key information to be delivered rather than how to handle the media. Once more preparation helps by making sure the various spokespersons have the proper media relations training and skills.

Quickness and accuracy play an important role in public safety. When public safety is a concern, people need to know what they must do to protect themselves. Sturges (1994) refer to this information as instructing information. Instructing information must be quick and accurate to be useful. For instance, people must know as soon as possible not to eat contaminated foods or to shelter-in-place during a chemical release. A slow or inaccurate response can increase the risk of injuries and possibly deaths. Quick actions can also save money by preventing further damage and protecting reputations by showing that the organization is in control. However, speed is meaningless if the information is wrong. Inaccurate information can increase rather than decrease the threat to public safety.

The news media are drawn to crises and are a useful way to reach a wide array of publics quickly. So it is logical that crisis response research has devoted considerable attention to media relations. Media relations allows crisis managers to reach a wide range of stakeholders fast. Fast and wide ranging is perfect for public safety—get the message out quickly and to as many people as possible. Clearly there is a waste as non-targets receive the message but speed and reach are more important at the initial stage of the crisis. However, the news media is not the only channel crisis managers can and should use to reach stakeholders.

Web sites, social media, Intranet sites, enterprise social network, and mass notification systems add to the news media coverage and help to provide a quick response. Crisis managers can supply greater amounts of their own information on a web site. Moreover, a growing percentage of stakeholders are relying on social media to get their news, including information about organizations that are relevant to them (Holcomb, Gottfried & Mitchell, 2013). We must assume there is a segment of customers that use the organization’s social media to get information about the organization. Not all targets will use the organization’s web site or social media but enough do to justify the inclusion of web-based communication in a crisis response. Taylor and Kent’s (2007) extensive analysis of crisis web sites over a multiyear period found a slow progression in organizations utilizing web sites and the interactive nature of the web during a crisis. The evidence for social media is not as clear but a similar pattern does seem to be emerging. Mass notification systems deliver short messages to specific individuals through a mix of phone, text messaging, voice messages, and e-mail. The systems also allow people to send responses. In organizations with effective Intranet systems/enterprise social networks, the internal system is a useful vehicle for reaching employees as well. If an organization integrates its Intranet/enterprise social network with suppliers and customers, these stakeholders can be reached as well.

Crisis experts have recommended a third component to an initial crisis response, crisis managers should express concern/sympathy for any victims of the crisis. Victims are the people that are hurt or inconvenienced in some way by the crisis. Victims might have lost money, become ill, had to evacuate, or suffered property damage. Kellerman (2006) details when it is appropriate to express regret. Expressions of concern help to lessen reputational damage and to reduce financial losses. Experimental studies by Coombs and Holladay (1996) and by Dean (2004) found that organizations did experience less reputational damage when an expression of concern is offered verses a response lacking an expression of concern. Cohen (1999) examined legal cases and found early expressions of concern help to reduce the number and amount of claims made against an organization for the crisis. Many other studies support the value of a victim, focus (e.g., Holladay & Coombs, 2013; Kriyantono, 2012; Schwarz, 2012).

However, Tyler (1997) reminds us that there are limits to expressions of concern. Lawyers may try to use expressions of concern as admissions of guilt. A number of states have laws that protect expressions of concern from being used against an organization. Another concern is that as more crisis managers express concern, the expressions of concern may lose their effect of people. Hearit (2007) cautions that expressions of concern will seem too routine. Still, a failure to provide a routine response could hurt an organization. Hence, expressions of concern may be expected and provide little benefit when used but can inflict damage when not used.

Argenti (2002) interviewed a number of managers that survived the 9/11 attacks. His strongest lesson was that crisis managers should never forget employees are important publics during a crisis. The Business Roundtable (2002) and Corporate Leadership Council (2003) remind us that employees need to know what happened, what they should do, and how the crisis will affect them. The earlier discussions of mass notification systems and the Intranet are examples of how to reach employees with information. West Pharmaceuticals had a production facility in Kinston, North Carolina leveled by an explosion in January 2003. Coombs (2004b) examined how West Pharmaceuticals used a mix of channels to keep employees apprised of how the plant explosion would affect them in terms of when they would work, where they would work, and their benefits. Moreover, Coombs (2015) identifies research that suggests well informed employees provide an additional channel of communication for reaching other stakeholders.

When the crisis results in serious injuries or deaths, crisis management must include stress and trauma counseling for employees and other victims. One illustration is the trauma teams dispatched by airlines following a plane crash. The trauma teams address the needs of employees as well as victims’ families. Both the Business Roundtable (2002) and Coombs (2015) note that crisis managers must consider how the crisis stress might affect the employees, victims, and their families. Organizations must provide the necessary resources to help these groups cope.

We can take a specific set of both form and content lessons from the writing on the initial crisis response. Table 4 provides a summary of the Initial Crisis Response Best Practices. Form refers to the basic structure of the response. The initial crisis response should be delivered in the first hour after a crisis and be vetted for accuracy. Content refers to what is covered in the initial crisis response. The initial message must provide any information needed to aid public safety, provide basic information about what has happened, and offer concern if there are victims. In addition, crisis managers must work to have a consistent message between spokespersons.

Table 4: Initial Crisis Response Best Practices

- Be quick and try to have initial response within the first hour.

- Be accurate by carefully checking all facts.

- Be consistent by keeping spokespeople informed of crisis events and key message points.

- Make public safety the number one priority.

- Use all of the available communication channels including the social media, web sits, Intranet, and mass notification systems.

- Provide some expression of concern/sympathy for victims

- Remember to include employees in the initial response.

- Be ready to provide stress and trauma counseling to victims of the crisis and their families, including employees.

Reputation Repair and Behavioral Intentions

A number of researchers in public relations, communication, and marketing have shed light on how to repair the reputational damage a crisis inflicts on an organization. At the center of this research is a list of reputation repair strategies. Bill Benoit (1995; 1997) has done the most to identify the reputation repair strategies. He analyzed and synthesized strategies from many different research traditions that shared a concern for reputation repair. Coombs (2007) integrated the work of Benoit with others to create a master list that integrated various writings into one list. Table 5 presents the Master List of Reputation Repair Strategies. The reputation repair strategies vary in terms of how much they accommodate victims of this crisis (those at risk or harmed by the crisis). Accommodate means that the response focuses more on helping the victims than on addressing organizational concerns. The master list arranges the reputation repair strategies from the least to the most accommodative reputation repair strategies. (For more information on reputation repair strategies see also Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger, 2006).

Table 5: Master List of Reputation Repair Strategies

- Attack the accuser: crisis manager confronts the person or group claiming something is wrong with the organization.

- Denial: crisis manager asserts that there is no crisis.

- Scapegoat: crisis manager blames some person or group outside of the organization for the crisis.

- Excuse: crisis manager minimizes organizational responsibility by denying intent to do harm and/or claiming inability to control the events that triggered the crisis.

- Provocation: crisis was a result of response to some one else’s actions.

- Defeasibility: lack of information about events leading to the crisis situation.

- Accidental: lack of control over events leading to the crisis situation.

- Good intentions: organization meant to do well

- Justification: crisis manager minimizes the perceived damage caused by the crisis.

- Reminder: crisis managers tell stakeholders about the past good works of the organization.

- Ingratiation: crisis manager praises stakeholders for their actions.

- Compensation: crisis manager offers money or other gifts to victims.

- Apology: crisis manager indicates the organization takes full responsibility for the crisis and asks stakeholders for forgiveness.

It should be noted that reputation repair can be used in the crisis response phase, post-crisis phase, or both. Not all crises need reputation repair efforts. Frequently the instructing information and expressions of concern are enough to protect the reputation. When a strong reputation repair effort is required, that effort will carry over into the post-crisis phase. Or, crisis managers may feel more comfortable waiting until the post-crisis phase to address reputation concerns.

A list of reputation repair strategies by itself has little utility. Researchers have begun to explore when a specific reputation repair strategy or combination of strategies should be used. These researchers frequently have used attribution theory to develop guidelines for the use of reputation repair strategies. A short explanation of attribution theory is provided along with its relationship to crisis management followed by a summary of lessons learned from this research.

Attribution theory believes that people try to explain why events happen, especially events that are sudden and negative. Generally, people either attribute responsibility for the event to the situation or the person in the situation. Attributions generate emotions and affect how people interact with those involved in the event. Crises are negative (create damage or threat of damage) and are often sudden so they create attributions of responsibility. People either blame the organization in crisis or the situation. If people blame the organization, anger is created and people react negatively toward the organization. Three negative reactions to attributing crisis responsibility to an organization have been documented: (1) increased damage to an organization’s reputation, (2) reduced purchase intentions and (3) increased likelihood of engaging in negative word-of-mouth (Coombs, 2007; Coombs & Holladay, 2006).

Most of the research has focused on establishing the link between attribution of crisis responsibility and the threat to the organization’s reputation. A number of studies have proven this connection exists (Claeys, Cauberghe & Vyncke, 2010; Cooley & Cooley, 2010; Coombs 2004a; Coombs & Holladay, 1996; Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Coombs & Holladay, 2006). The research linking organizational reputation with purchase intention and negative word-of-mouth is less developed but so far has confirmed these two links as well (Coombs, 2007b; Coombs & Holladay, 2006).

Coombs (1995) pioneered the application of attribution theory to crisis management in the public relations literature. His 1995 article began to lay out a theory-based approach to matching the reputation repair strategies to the crisis situation. A series of studies have tested the recommendations and assumptions such as Coombs and Holladay (1996), Coombs & Holladay, (2002) and Coombs (2004a), and Coombs, (2007). This research has evolved into the Situation Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT). SCCT argues that crisis managers match their reputation repair strategies to the reputational threat of the crisis situation. Crisis managers should use increasingly accommodative the reputation repair strategies as the reputational threat from the crisis intensifies (Coombs & Holladay, 1996; Coombs, 2007b; Fussell Sisco, Collins & Zoch, 2010; Weber, Erickson & Stone, 2011).

Crisis managers follow a two-step process to assess the reputational threat of a crisis. The first step is to determine the basic crisis type. A crisis manager considers how the news media and other stakeholders are defining the crisis. Coombs and Holladay (2002) had respondents evaluate crisis types based on attributions of crisis responsibility. They distilled this data to group the basic crises according to the reputational threat each one posed. Table 6 provides a list the basic crisis types and their reputational threat.

Table 6: Crisis Types by Attribution of Crisis Responsibility

- Victim Crises: Minimal Crisis Responsibility

- Natural disasters: acts of nature such as tornadoes or earthquakes.

- Rumors: false and damaging information being circulated about you organization.

- Workplace violence: attack by former or current employee on current employees on-site.

- Product Tampering/Malevolence: external agent causes damage to the organization.

- Accident Crises: Low Crisis Responsibility.

- Challenges: stakeholder claim that the organization is operating in an inappropriate manner.

- Technical-error accidents: equipment or technology failure that cause an industrial accident.

- Technical-error product harm: equipment or technology failure that cause a product to be defective or potentially harmful.

- Preventable Crises: Strong Crisis Responsibility.

- Human-error accidents: industrial accident caused by human error.

- Human-error product harm: product is defective or potentially harmful because of human error.

- Organizational misdeed: management actions that put stakeholders at risk and/or violate the law.

The second step is to review the intensifying factors of crisis history and prior reputation. If an organization has a history of similar crises or has a negative prior reputation, the reputational threat is intensified. A series of experimental studies have documented the intensifying value of crisis history (Coombs, 2004a) and prior reputation (Coombs & Holladay, 2001; Coombs & Holladay, 2006; Klein & Dawar, 2004). The same crisis was found to be perceived as having much strong crisis responsibility (a great reputational threat) when the organization had either a previous crisis (Coombs, 2004a) or the organization was known not to treat stakeholders well/negative prior reputation (Coombs & Holladay, 2001; Coombs & Holladay, 2006; Klein & Dewar, 2004). Table 7 is a set of crisis communication best practices derived from attribution theory-based research in SCCT (Coombs, 2007, Coombs & Holladay, 1996; Coombs & Holladay, 2001; Coombs & Holladay, 2006). SCCT argues that any crisis that creates victims must have a base response that provides instructing information (tells stakeholders how to protect themselves physically from a crisis) and a care response (help stakeholders cope psychologically with a crisis) (Claeys, Cauberghe & Vyncke, 2010; Cooley & Cooley, 2010; Coombs, 2007).

Table 7: Attribution Theory-based Crisis Communication Best Practices

- All victims or potential victims should receive instructing information, including recall information. This is one-half of the base response to a crisis.

- All victims should be provided an expression of sympathy, any information about corrective actions and trauma counseling when needed. This can be called the “care response.” This is the second-half of the base response to a crisis.

- For crises with minimal attributions of crisis responsibility and no intensifying factors, instructing information and care response is sufficient.

- For crises with minimal attributions of crisis responsibility and an intensifying factor, add excuse and/or justification strategies to the instructing information and care response.

- For crises with low attributions of crisis responsibility and no intensifying factors, add excuse and/or justification strategies to the instructing information and care response.

- For crises with low attributions of crisis responsibility and an intensifying factor, add compensation and/or apology strategies to the instructing information and care response.

- For crises with strong attributions of crisis responsibility, add compensation and/or apology strategies to the instructing information and care response.

- The compensation strategy is used anytime victims suffer serious harm.

- The reminder and ingratiation strategies can be used to supplement any response.

- Denial and attack the accuser strategies are best used only for rumor and challenge crises.

In general, a reputation is how stakeholders perceive an organization. A reputation is widely recognized as a valuable, intangible asset for an organization and is worth protecting. But the threat posed by a crisis extends to behavioral intentions as well. Increased attributions of organizational responsibility for a crisis result in a greater likelihood of negative word-of-mouth about the organization and reduced purchase intention from the organization. Early research suggests that lessons designed to protect the organization’s reputation will help to reduce the likelihood of negative word-of-mouth and the negative effect on purchase intentions as well (Coombs, 2007).

Social media provide a unique set of evaluative data during a crisis. Crisis managers can determine how stakeholders are reacting to their crisis messages. There are limitations to the social media response data because it only includes those who are willing to post messages and might provide a biases view of stakeholder reactions. Social media comments have been used to evaluate how stakeholders (typically customers) have reacted to crisis experienced by Amazon.com, Alitalia Airlines, and the LiveStrong charity (Coombs & Holladay, 2012; Coombs & Holladay, 2014; Valentini & Romenti, 2011). In each study, the amount and valence of the responses were examined to determine if stakeholders were reacting positively or negatively to the crisis communication strategies. In the Amazon.com case, the initial negative reaction resulted in a second crisis response that was much more effective. The negative posts suggested what Amazon.com needed to do to improve its response. Whether or not they used this feedback, the second crisis message did address the key criticism found in the posts (Coombs & Holladay, 2012).

Emotions are a final component to consider in the crisis response. Crises can generate strong emotions. Researchers have focused on anger, sympathy, anxiety as the primary fears that arise from a crisis. Stakeholder emotions help to shape their reactions to the crisis. For instance, stakeholders are likely to support an organization in crisis if they have sympathy for the organization but will take negative actions toward the organization if they are angry toward the organization (Coombs & Holladay, 2007). Emotions can influence the type of information stakeholders desire during a crisis. The implications are that the emotions generated by a crisis will affect the crisis response strategies and organization utilizes (Holladay & Coombs, 2013; Jin, 2014; Jin, Liu, Anagondahalli, & Austin, 2014). For example, anxiety creates a strong need for adjusting information—messages to help stakeholders cope emotionally with the crisis. More research is necessary to clarify the value of factoring stakeholder emotions into the formulation of crisis response strategies.

Post-Crisis Phase

In the post-crisis phase, the organization is returning to business as usual. The crisis is no longer the focal point of management’s attention but still requires some attention. As noted earlier, reputation repair may be continued or initiated during this phase. There is important follow-up communication that is required. First, crisis managers often promise to provide additional information during the crisis phase. The crisis managers must deliver on those informational promises or risk losing the trust of publics wanting the information. Second, the organization needs to release updates on the recovery process, corrective actions, and/or investigations of the crisis. The amount of follow-up communication required depends on the amount of information promised during the crisis and the length of time it takes to complete the recovery process. If you promised a reporter a damage estimate, for example, be sure to deliver that estimate when it is ready. West Pharmaceuticals provided recovery updates for over a year because that is how long it took to build a new facility to replace the one destroyed in an explosion.

The digital environment is idea for providing updates. For instance, Twitter is heralded for its ability to pass along information as a story develops (Mitchell & Gustin, 2013). This is similar to the value many observed for Intranets. Dowling (2003), the Corporate Leadership Counsel (2003), and the Business Roundtable (2002) all observed that Intranets are an excellent way to keep employees updated, if the employees have ways to access the site. The same advice holds true if you call the Intranet enterprise social networking. Mass notification systems can be used as well to deliver update messages to employees and other publics via phones, text messages, voice messages, and e-mail. Personal e-mails and phone calls can be used to provide follow-up information as well.

Crisis managers agree that a crisis should be a learning experience. The crisis management effort needs to be evaluated to see what is working and what needs improvement. The same holds true for crisis exercises. Every crisis management exercise should be carefully dissected as a learning experience. The organization should seek ways to improve prevention, preparation, and/or the response. As most books on crisis management note, those lessons are then integrated into the pre-crisis and crisis response phases. That is how management learns and improves its crisis management process. However, experts have found organizations are very bad at learning from crises. This poor learning is due to an inability to be honest about the self-assessment of a crisis effort (Deverel, 2010; Elliott & Macpherson, 2010).

Social media have heightened the importance of remembering a crisis. Crisis remembering is about honoring the victims of the crisis. Two salient aspects of remembering for crisis management are anniversaries and memorials. Anniversaries, especially the first, can result in events to commemorate the crisis. Organizations must be careful to consider how to mark the anniversary and the proper level of involvement in the event for the organization, survivors, and the families of victims. The mishandling of the first anniversary of the Costa Concordia sinking created additional ill will between Carnival Cruise and survivors of the tragic event. Memorials can be physical or digital. West Pharmaceuticals has a physical memorial in their facility to commemorate those who died in the 2007 explosion. An online memorial was created for the 11 workers who died when the Deepwater Horizon sank. Organizations must decide if and how they will become involved in memorials. The best advice is to consult with victims and the families of victims to determine what level of organizational involvement they feel is appropriate (Coombs, 2015). Table 8 lists the Post-Crisis Phase Best Practices.

Table 8: Post-Crisis Phase Best Practices

- Deliver all information promised to stakeholders as soon as that information is known.

- Keep stakeholders updated on the progression of recovery efforts including any corrective measures being taken and the progress of investigations.

- Analyze the crisis management effort for lessons and integrate those lessons in to the organization’s crisis management system.

- Scan the Internet channels for online memorials.

- Consult with victims and their families to determine the organization’s role in any anniversary events or memorials.

Conclusion

It is difficult to distill all that is known about crisis management into one, concise entry. I have tried to identify the best practices and lessons created by crisis management researchers and analysts. While crises begin as a negative/threat, effective crisis management can minimize the damage and in some case allow an organization to emerge stronger than before the crisis. However, crises are not the ideal way to improve an organization. Because no organization is immune from a crisis so all must do their best to prepare for one. This entry provides a revised set of ideas that can be incorporated into an effective crisis management program. At the end of this revised entry is an updated annotated bibliography. The annotated bibliography provides short summaries of key writings in crisis management highlighting. Each entry identifies the main topics found in that entry and provides citations to help you locate those sources.

Annotated Bibliography

Argenti, P. (2002, December). Crisis communication: Lessons from 9/11. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 103-109. This article provides insights into working with employees during a crisis. The information is derived from interviews with managers about their responses to the 9/11 tragedies.

Arpan, L.M., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R. (2005). Stealing thunder: An analysis of the effects of proactive disclosure of crisis information. Public Relations Review 31(3), 425-433.

This article discusses an experiment that studies the idea of stealing thunder. Stealing thunder is when an organization releases information about a crisis before the news media or others release the information. The results found that stealing thunder results in higher credibility ratings for a company than allowing others to report the crisis information first. This is additional evidence to support the notion of being quick in a crisis and telling the organization’s side of the story.

Augustine, N. R. (1995, November/December). Managing the crisis you tried to prevent. Harvard Business Review, 73(6), 147-158. This article centers on the six stages of a crisis: avoiding the crisis, preparing to management the crisis, recognizing the crisis, containing the crisis, resolving the crisis, and profiting from the crisis. The article reinforces the need to have a crisis management plan and to test both the crisis management plan and team through exercises. It also reinforces the need to learn (profit) from the crisis.

Barton, L. (2001). Crisis in organizations II (2nd ed.). Cincinnati, OH: College Divisions South-Western. This is a very practice-oriented book that provides a number of useful insights into crisis management. There is a strong emphasis on the role of communication and public relations/affairs in the crisis management process and the need to speak with one voice. The book provides excellent information on crisis management plans (a template is in Appendix D pp. 225-262); the composition of crisis management teams (pp. 14-17); the need for exercises (pp. 207-221); and the need to communicate with employees (pp. 86-101).

Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: A theory of image restoration. Albany: State University of New York Press. This book has a scholarly focus on image restoration not crisis manage. However, his discussion of image restoration strategies is very thorough (pp. 63-96). These strategies have been used as reputation repair strategies after a crisis.

Benoit, W. L. (1997). Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relations Review, 23(2), 177-180. The article is based on his book Accounts, excuses, and apologies: A theory of image restoration and provides a review of image restoration strategies. The image restoration strategies are reputation repair strategies that can be used after a crisis. It is a quicker and easiest to use resource than the book.

Business”>http://www.nfib.com/object/3783593.html.”>Business Roundtable’s Post-9/11 crisis communication toolkit. (2002). Retrieved April 24, 2006, from http://www.nfib.com/object/3783593.html.

This is a very user-friendly PDF files that takes a person through the crisis management process. There is helpful information on web-based communication (pp. 73-82) including “dark sites” and the use of Intranet and e-mail to keep employees informed. There is an explanation of templates, what are called holding statements or fill-in-the-blank media statements including a sample statement (pp. 28-29). It also provides information of the crisis management plan (pp. 21-32), structure of the crisis management team (pp. 33-40) and types of exercises (pp. 89-93) including mock press conferences.

Carney, A., & Jorden, A. (1993, August). Prepare for business-related crises. Public Relations Journal 49, 34-35.

This article emphasize the need for a message strategy during crisis communication. Developing and sharing a strategy helps an organization to speak with one voice during the crisis.

Claeys, A. S., & Cauberghe, V. (2012). Crisis response and crisis timing strategies, two sides of the same coin. Public Relations Review, 38(1), 83-88. The researchers demonstrated the power of stealing thunder in protecting reputations. When an organization stole thunder, the type of crisis response had no effect on the reputation. However, when the organization did not steal thunder, the recommended crisis response strategies for Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) were effective at repairing reputations.

Claeys, A. S., Cauberghe, V., & Vyncke, P. (2010). Restoring reputations in times of crisis: An experimental study of the Situational Crisis Communication Theory and the moderating effects of locus of control. Public Relations Review, 36(3), 256-262. This study showed the locus of control did have an effect on recommendations and effects specified by Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT).

Cohen, J. R. (1999). Advising clients to apologize. S. California Law Review, 72, 1009-131.

This article examines expressions of concern and full apologies from a legal perspective. He notes that California, Massachusetts, and Florida have laws that prevent expressions of concern from being used as evidence against someone in a court case. The evidence from court cases suggests that expressions of concern are helpful because they help to reduce the amount of damages sought and the number of claims filed.

Cooley, S. C., & Cooley, A. B. (2011). An examination of the situational crisis communication theory through the General Motors bankruptcy. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 3(6), 203-211. A case study of General Motors communication during its bankruptcy is examined using Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT).

Coombs, W. T. (1995). Choosing the right words: The development of guidelines for the selection of the “appropriate” crisis response strategies. Management Communication Quarterly, 8, 447-476.

This article is the foundation for Situational Crisis Communication Theory. It uses a decision tree to guide the selection of crisis response strategies. The guidelines are based on matching the response to nature of the crisis situation. A number of studies have tested the guidelines in the decision tree and found them to be reliable.

Coombs, W. T. (2004a). Impact of past crises on current crisis communications: Insights from situational crisis communication theory. Journal of Business Communication, 41, 265-289.

This article documents that past crises intensify the reputational threat to a current crisis. Since the news media reminds people of past crises, it is common for organizations in crisis to face past crises as well. Crisis managers need to adjust their reputation repair strategies if there are past crises-crisis managers will need to use more accommodative strategies than they normally would. Accidents are a good example. Past accidents indicate a pattern of problems so people will view the organization as much more responsible for the crisis than if the accident were isolated. Greater responsibility means the crisis is more of a threat to the reputation and the organization must focus the response more on addressing victim concerns.

Coombs, W. T. (2004b). Structuring crisis discourse knowledge: The West Pharmaceutics case. Public Relations Review, 30, 467-474.

This article is a case analysis of the West Pharmaceutical 2003 explosion at its Kinston, NC facility. The case documents the extensive use of the Internet to keep employees and other stakeholders informed. It also develops a list of crisis communication standards based on SCCT. The crisis communication standards offer suggestions for how crisis managers can match their crisis response to the nature of the crisis situation.

Coombs, W. T. (2006). Code red in the boardroom: Crisis management as organizational DNA. Westport, CN: Praeger.

This is a book written for a practitioner audience. The book focuses on how to respond to three common types of crises: attacks on an organization (pp. 13-26), accidents (pp. 27-44), and management misbehavior pp. (45-64). There are also detailed discussions of how crisis management plans must be a living document (pp. 77-90), different types of exercises for crisis management (pp. 84-87), and samples of specific elements of a crisis management plan in Appendix A (pp. 103-109).

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis:The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10, 1-14.

This article provides a summary of research conducted on and lessons learned from Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT). The article includes a discussion how the research can go beyond reputation to include behavioral intentions such as purchase intention and negative word-of-mouth. The information in the article is based on experimental studies rather than case studies.

Coombs, W. T. (2015). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, Managing, and responding (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. This book is designed to teach students and managers about the crisis management process. There is a detailed discussion of spokesperson training pp. (80-88) and a discussion of the traits and skills crisis team members need to have to be effective during a crisis (pp. 68-79). The book emphasizes the value of follow-up information and updates (pp. 172-176) along with the learning from the crisis (pp. 170-172). There is also a discussion of the utility of mass notification systems during a crisis (p. 101).

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (1996). Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study of crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(4), 279-295. This article uses an experimental design to document the negative effect of crises on an organization’s reputation. The research also establishes that the type of reputation repair strategies managers use does make a difference on perceptions of the organization. An important finding is proof that the more an organization is held responsible for the crisis, the more accommodative a reputation repair strategy must be in order to be effective/protect the organization’s reputation.

Coombs, W. T. and Holladay, S. J. (2001). An extended examination of the crisis

situation: A fusion of the relational management and symbolic approaches. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13, 321-340.

This study reports on an experiment designed to test how prior reputation influenced the attributions of crisis responsibility. The study found that an unfavorable prior reputation had the biggest effect. People rated an organization as having much greater responsibility for a crisis when the prior reputation was negative than if the prior reputation was neutral or positive. Similar results were found for the effects of prior reputation on the post-crisis reputation.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16, 165-186. This article begins to map how stakeholders respond to some very common crises. Using the level of responsibility for a crisis that people attribute to an organization, the research found that common crises can be categorized into one of three groups: victim cluster has minimal attributions of crisis responsibility (natural disasters, rumors, workplace violence, and tampering), accidental cluster has low attributions of crisis responsibility (technical-error product harm and accidents), and preventable cluster has strong attributions of crisis responsibility (human-error product harm and accidents, management misconduct, and organizational misdeeds). The article recommends different crisis response strategies depending upon the attributions of crisis responsibility.

Coombs, W. T. & Holladay, S. J. (2006). Halo or reputational capital: Reputation and crisis management. Journal of Communication Management, 10(2), 123-137.

This article examines if and when a favorable pre-crisis reputation can protect an organization with a halo effect. The halo effect says that strong positive feelings will allow people to overlook a negative event-it can shield an organization from reputational damage during a crisis. The study found that only in a very specific situation does a halo effect occur. In most crises, the reputation is damaged suggesting reputational capital is a better way to view a strong, positive pre-crisis reputation. An organization accumulates reputational capital by positively engaging publics. A crisis causes an organization to loss some reputational capital. The more pre-crisis reputational capital, the stronger the reputation will be after the crisis and the easier it should be to repair.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2012). Amazon. com’s Orwellian nightmare: exploring apology in an online environment. Journal of Communication Management, 16(3), 280-295. The article demonstrated the value of online reactions by stakeholders to assess the effectiveness of a crisis communication effort including the need for additional communication.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, J. S. (2012). The paracrisis: The challenges created by publicly managing crisis prevention. Public Relations Review, 38(3), 408-415. This article articulates the idea of a paracrisis. The paracrisis looks like a crisis but is actually a crisis risk that must be managed publicly. Failure to properly manage a paracrisis can result in the situation escalating into a crisis.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2014). How publics react to crisis communication efforts: Comparing crisis response reactions across sub-arenas. Journal of Communication Management, 18(1), 40-57. This article demonstrates the value of online reactions to evaluate an organization’s crisis communication effort.

Corporate Leadership Council. (2003). Crisis management strategies. Retrieved September 12, 2006, from http://www.executiveboard.com/EXBD/Images/PDF/Crisis%20Management%20Strategies.pdf. [Now available here]

This online PDF file summarizes key crisis management insights from the Corporate Leadership Council. The topics include the value and elements of a crisis management plan (pp 1-3), structure of a crisis management team (pp. 4-6), communicating with employees (pp. 7-9), using web sites including “dark sites” (p. 7), using pre-packaged information/templates (p. 7), and the value of employee assistance programs (p. 10). The file is an excellent overview to key elements of crisis management with an emphasis on using new technology.

Dean, D. H. (2004. Consumer reaction to negative publicity: Effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event. Journal of Business Communication, 41, 192-211.

This article reports an experimental study that included a comparison how people reacted to expressions of concern verses no expression of concern. Post-crisis reputations were stronger when an organization provided an expression of concern.

Deverell, E. (2010). Flexibility and Rigidity in Crisis Management and Learning at Swedish Public Organizations. Public Management Review, 12(5), 679-700. The study notes that organizations have difficulty learning from crises.

Dilenschneider, R. L. (2000). The corporate communications bible: Everything you need to know to become a public relations expert. Beverly Hills: New Millennium. This book has a strong chapter of crisis communication (pp. 120-142). It emphasizes how a crisis is a threat to an organization’s reputation and the need to be strategic with the communications response.

Downing, J. R. (2003). American Airlines’ use of mediated employee channels after the 9/11 attacks. Public Relations Review, 30, 37-48.

This article reviews how American Airlines used its Intranet, web sites, and reservation system to keep employees informed after 9/11. The article also comments on the use of employee assistance programs after a traumatic event. Recommendations include using all available channels to inform employees during and after a crisis as well as recommending organizations “gray out” color from their web sites to reflect the somber nature of the situation.

Elliott, D., & Macpherson, A. (2010). Policy and practice: Recursive learning from crisis. Group & Organization Management, 35(5), 572-605. This article emphasized the general failure of organizations to learn from their crises.

Fearn-Banks, K. (2001). Crisis communications: A casebook approach (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. This book is more a textbook for students using case studies. Chapter 2 (pp. 18-33) has a useful discussion of elements of the crisis communication plan, a subset of the crisis management plan. Chapter 4 has some tips on media relations (pp. 63-71).

Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2011). The study of internal crisis communication: towards an integrative framework. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(4), 347-361. This article calls for more research into internal crisis communication due to the stress crises create for employees. It also argues for the value of employees as ambassadors during a crisis.

Fussell Sisco, H., Collins, E. L., & Zoch, L. M. (2010). Through the looking glass: A decade of Red Cross crisis response and situational crisis communication theory. Public Relations Review, 36(1), 21-27. The article applies guidance from Situational Crisis Communication (SCCT) to explain the behavior of a non-profit organization during crises.

Hearit, K. M. (1994, Summer). Apologies and public relations crises at Chrysler, Toshiba, and Volvo. Public Relations Review, 20(2), 113-125.

This article provides a strong rationale for the value of quick but accurate crisis response. The focus is on how a quick response helps an organization to control the crisis situation.

Hearit, K. M. (2006). Crisis management by apology: Corporate response to

allegations of wrongdoing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

This book is a detailed, scholarly treatment of apologies that has direct application to crisis management. Chapter 1 helps to explain the different ways the term

apology is used and concentrates on how it should be treated as a public acceptance of responsibility (pp. 1-18). Chapter 3 details the legal and liability issues involved when an organization chooses to use an apology.

Holladay, S. J., & Coombs, W. T. (2013). Successful prevention may not be enough: A case study of how managing a threat triggers a threat. Public Relations Review, 39(5), 451-458. This case explores how efforts to manage a crisis risk can trigger a crisis if handled ineffectively. There is also an elaboration of instructing and adjusting information.

Jin, Y. (2014). Examining publics’ crisis responses according to different shades of anger and sympathy. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(1), 79-101. This research develops the idea of how the emotional reaction of a person during a crisis helps to determine the type of information they need to receive from crisis communication messages.

Jin, Y., Liu, B. F., Anagondahalli, D., & Austin, L. (2014). Scale development for measuring publics’ emotions in organizational crises. Public Relations Review. This article reports the results of efforts to develop a scale that can be used to measure emotional reactions during a crisis. Emotions matter because they can what type of information people need to receive during a crisis.

Johansen, W., Aggerholm, H. K., & Frandsen, F. (2012). Entering new territory: A study of internal crisis management and crisis communication in organizations. Public Relations Review, 38(2), 270-279. This study examines the internal crisis communication for Danish companies. They found around 40% of companies thought of employees as ambassadors during a crisis.

Kellerman, B. (2006, April). When should a leader apologize and when not? Harvard Business Review, 84(4), 73-81. This article defines an apology as accepting responsibility for a crisis and expressing regret. The value of apologies is highlighted along with suggestions for when an apology is appropriate and inappropriate. An apology should be used when it will serve an important purpose, the crisis has serious consequences, and the cost of an apology will be lower than the cost of being silent.