This blog post is presented by the IPR Commission on Measurement and Evaluation.

“Cause and effect” in marketing and communications is not always what its practitioners believe. Nike and United Airlines are excellent examples of how different external factors change the impact and business value that social controversy and corporate strategy ultimately deliver…or don’t.

After some brief scorching in social channels, Nike’s controversial gambit with Colin Kaepernick has proven a spectacular success. Revenue is up 31 percent in two weeks. The key question, however, is can they sustain it, and what will it take to make that happen? What role did an integrated strategy — using advertising, PR and social channels play — and what’s the effect of the larger business context?

As things stand today, advanced cause-and-effect analytics strongly suggest that Nike’s paid and earned efforts worked together in the short term to create the outcomes in revenue and stock price that we are seeing.

Likewise, it is clear today that the controversy that enveloped United Airlines in April 2017 had virtually no effect on the airline’s business performance beyond a short-term drop in share price.

The most recent Cone Social Impact Research, found that today’s shoppers, and particularly younger shoppers, expect companies to take a strong stand on social issues and will reward companies that do, and punish companies that don’t. In that context, the Nike ad makes perfect sense. However, as powerful as social activism via highly empathetic marketing and communications can be, other market factors can be even more material under certain circumstances.

Three of the most impactful are demand elasticity, customer sense of risk, and time lag.

Demand elasticity measures a change in the customer demand for a good or service when one or more market factors change. Risk is self-explanatory; time lag is the amount of elapsed time between a cause and an effect – an example in the natural world would be the number of seconds that transpire between a lightning flash and a thunderclap.

Let’s look at Nike first. Demand for Nike products is highly elastic, meaning that the customer demand for their products not only can be quickly improved but also quickly degraded. Nike has a lot of competitors, which makes customer demand even more elastic. However, most Nike customers don’t feel a lot of risk around the decision to purchase a pair of shoes, so the time lag from “I love Nike” to cha-ching can be pretty fast. We see this dynamic very often in retail and other short-cycle B2C.

The lack of intrinsic risk around buying a pair of shoes also means that Nike customers can be motivated emotionally. For example, many consumers want to feel a part of something greater than just buying shoes, so attaching the company to the right social cause can exert a powerful attraction. On the other hand, the problem is that once that emotional bell is rung, it gets harder and harder to ring it again and again in a short time frame. And that’s why new product and overall better customer experience is even more important for sustaining Nike revenue growth than the Kaepernick campaign or what follows.

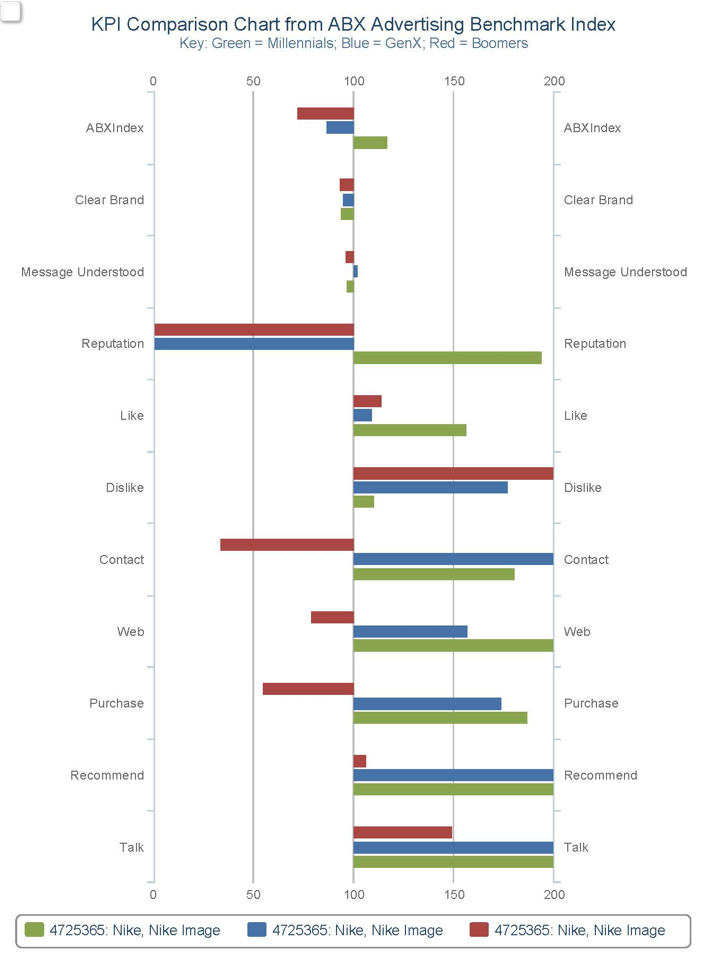

If you were to graph the past week or so for Nike, one of the biggest factors you might want to look at is whether there was any significant short-term improvement in the company’s Net Promoter Score (NPS), commonly understood as the level of customer enthusiasm and support for a vendor among the target audiences. And, in fact, that is exactly what ABX, a global advertising effectiveness research firm found. ABX has tested 150,000 ads in all media types. Their ABX Index is based on all those tests of ads over the years. Anything over 100 is above average, under 100 is below average. When they tested the :60 version of the Nike ad on a GenPop audience, it scored a 88 overall – significantly below average.

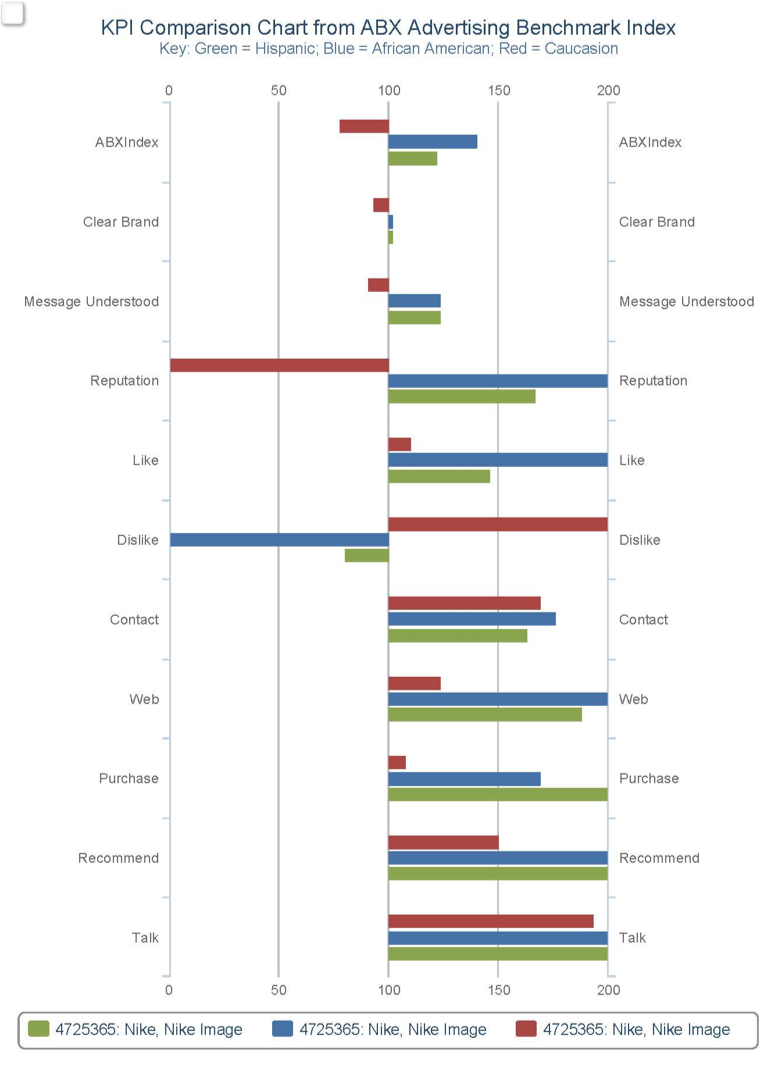

However, when you dive into the results for their specific target audiences (as we do in the chart to the left) – millennials and particularly African American and Hispanic men –the ad was a clear home run. It turns out that its ABX score was brought down by males over 55 who hated the ad, giving it an ABX Index of 43. But among African American and Hispanic audiences and among millennials it scored well above average.

Not that anyone really understood the message, ABX’s Message and Brand Clarity scores were dismal, indicating perhaps that the calls to action were stronger than the message itself.

Even more interesting, is ABX’s data on the impact the ad had on three other key factors that ABX tested: Purchase Intent, Recommendations and Likelihood of Talking about it with their friends and family. Among millennial men on the “Recommend” index, it scored an eye-popping 409 and a 392 among African Americans.

The spike in Nike sales also should come as no surprise after seeing the ABX data. On their “Purchase” score, Hispanics gave it a 261 and millennium males of all ethnicities gave it a 242. Similarly, the volume of chatter about the ad was to be expected given that those same groups gave it a 350 and 360 respectively on the Talk About index.

Given that buying a pair of shoes is more of an impulse purchase with little attendant risk, we see a rapid conversion of this spiking support into strong sales. This short-cycle volatility is common in many B2C business cycles, and it is one reason why you see so much promotion in that sector.

Nike also had adopted a far more “political campaign” approach to the release of the Kaepernick ad, positioning it very much as an “agent provocateur” in the marketplace and supporting that positioning with a slew of pro-active PR efforts.

Proof Analytics CEO Mark Stouse interviewed a senior leader at Nike for this article, who indicated that the company’s strategy sought to leverage the clear division in the marketplace over Kaepernick and the #TakeAKnee controversy. Nike’s campaign knew the ad would inflame the conservative audiences, leading directly to the rapid activation of that base. What’s interesting is that Nike was actually counting on the anti-Kaepernick portion of the audience to come out swinging hard in the first 24-48 hours after the ad campaign was released. This, in turn, would both activate a strong base of support for free speech and strengthen the Nike brand with their buying audience. Nike’s strategy represents a real jujitsu move against Kaepernick’s opponents, using them both to reignite the cause of free speech and motivate his supporters to buy shoes, almost in the same spirit as a campaign donation but with the added benefit of wearing a new, branded pair of Nike shoes.

In terms of marketing tactics, the Kaepernick ad campaign is the anchor for a swirl of earned media and social interaction – the two are mutually reinforcing. The highest correlation to Nike’s improved sales in the short term is social engagement; it also is the most perishable over time. Moving forward, we should expect to see a fall-off in sales and engagement as the short-term demand balloon is satisfied by everyone wanting to “support Nike,” followed by an undulating rise over the next 12 months as Nike presumably does other things designed to sustain the momentum and get to a new sustainable level of growth.

Against this likely positive trend line will come negative coverage of labor rights issues overseas and other problems that Nike continues to have. Some will be pushed by the opposition, (be it competitors or the anti-Kaepernick crowd) designed to reveal a corporate hypocrisy. Some will stick, some won’t, but the net/net is that demand for Nike’s products is very elastic, meaning that what is easily improved is also easily degraded. The key takeaway is that Nike will have to continue to activate more consumer enthusiasm with more powerful campaigns and better products, or the residual business value of Kaepernick (or any other single campaign) will fade fast.

Now let’s look at United Airlines. Demand for United flights is very inelastic compared to Nike. Not as many competitors. Price is a dominant consideration, as is flight schedule. If their dates are flexible, many customers will wait for a cheaper fare, slowing the sales conversion.

In addition to price and schedule, most airline customers prioritize safety above social activism. They may vent their rage on social media when a doctor gets dragged off a plane, and they may “hate UA,” but in the end they will fly United if the airline has the best price and flight schedule for their needs.

This means that while United Airlines had to endure a lot of negative press and social media activity for several weeks, none of it meant a thing for the company’s major areas of business performance. Ridership continued to climb in the weeks and months after the scandals, despite escalating fares. Revenue kept climbing, and profitability improved. The short-term stock price hit was erased over the ensuing weeks, and institutional shareholders took advantage of the dip in UA share price to increase their holdings.

United also learned – but understandably will never say it out loud – that the inelastic demand for its products, combined with the safety priority, means that social activism is not a good business investment for the airline. Put another way, social activism gets them little upside, and not investing in it has little downside. In the ranking of customer priorities, it isn’t as important as price, schedule and safety. And that’s why United Airlines focuses on price, schedule and safety in their marketing and communications. The analytics tell them that as important as social principles may be to some, flyers are far more likely to switch to a competitor if United disrupts their travel or scares them to death in the air, than they would be if they didn’t agree with their social action, or lack thereof.

Weaving all of this together, marketers and communicators can take valuable lessons from Nike and United Airlines, despite the differences between the two companies:

- Know the business problem(s) you’re solving and invest accordingly.

- Polarized opinion and great controversy can help you, kill you, or mean nothing.

- Connect deeply with what motivates your customers and invest accordingly.

- Understand the “half-life” of your investments and invest accordingly.

- Understand where your risk lies and how quickly you can move past that zone.

Mark Stouse is CEO of Proof Analytics. He can be reached at mark.stouse@proofanalytics.ai. Follow him on Twitter @markstouse.

Katie Paine is the Publisher of The Measurement of Advisor and CEO of Paine Publishing. She can be reached at kdpaine@painepublishing.com. Follow her on Twitter @queenofmetrics.

Angela Jeffrey, APR, is Vice President Brand Management at Advertising Benchmark Index.She can be reached at angie@adbenchmark.com. Follow her on Twitter @ajeffrey1.