We’re facing a truth crisis in American public life, as facts and data play an ever-diminishing role in political and civil discourse and trust in once-respected sources of information declines. It’s a troubling and potentially toxic trend that poses significant challenges to the profession of publication relations– and to the very fabric of democracy, itself. But to what extent have public relations professionals contributed to the phenomenon? And how can PR help turn it around?

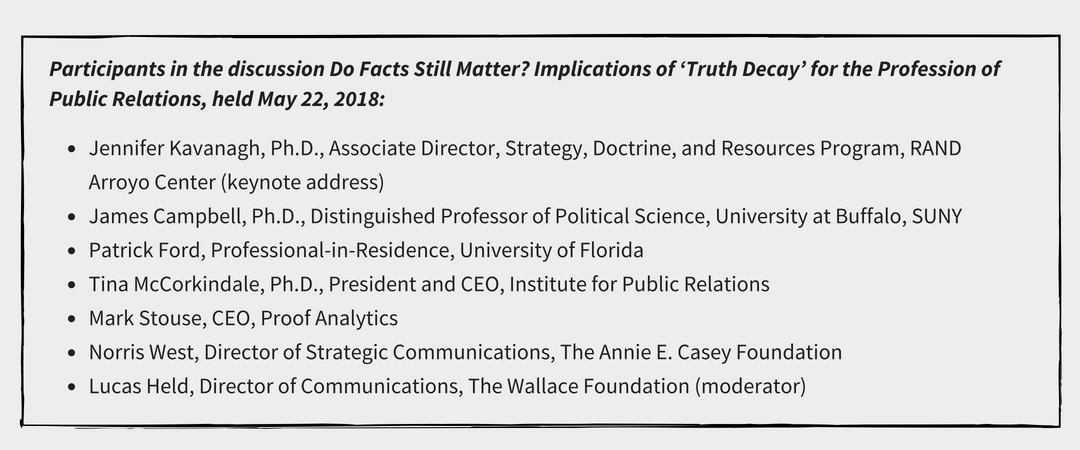

Those were the issues discussed at a recent presentation and panel discussion held by the Museum of Public Relations, in partnership with IPR in New York City. The event featured a presentation of key findings from Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life. A major new report from the RAND Corp., it examines the causes and consequences of this erosion of truth in the public sphere. But because public relations both shapes and is shaped by the information environment, a panel of five distinguished scholars and PR professionals also discussed the report’s implications for the profession.

Truth Decay focuses on a set of trends contributing to the blurring of fact and fiction, according to keynote speaker Jennifer Kavanagh, associate director of strategy, doctrine, and resources program at the RAND Arroyo Center, and the report’s co-author. The components of truth decay include disagreements about objective facts (think of the controversy over the safety of vaccines, despite many years of evidence pointing to their efficacy); a jumbling of fact and opinion in, for example, news programs that rely on commentary, rather than factual reporting; the increased volume and influence of subjective content across the communications landscape; and an escalating distrust in public institutions that once served as sources of factual information. “Most important is the complex interplay of these factors and how they amplify each other,” said Kavanagh.

The stakes, Kavanagh explained, are high. The disturbing results of truth decay include a deterioration of civil discourse, political paralysis, and disengagement from political and civic institutions and larger policy debates. “Democracy depends on people participating and taking an active role in their government,” she said. “If we lose that, it’s not clear we can have a healthy democracy.”

The panel discussion that followed focused on public relations professionals’ crucial role as creators and disseminators of information who depend on trust in the information environment. With that in mind, panelists wrestled with the question of whether the profession has contributed to—or even profited from—today’s truth decay. The surprising consensus: PR has, indeed, played a role in creating and perpetuating the phenomenon. That may be true, according to Tina McCorkindale, president and CEO of the Institute for Public Relations, when it comes to disseminating misinformation or omitting key facts. She emphasized that while bad actors comprise a small portion of the total profession, “I do think PR bears some responsibility for truth decay,” said McCorkindale. “It’s the responsibility of PR professionals to make sure what we say is true.”

At the same time, in most cases, practitioners don’t set out to conceal information deliberately, according to Norris West, director of strategic communications of The Annie E. Casey Foundation. “They end up hiding the truth through a series of small decisions,” he said. But the overall effect of those actions is to obfuscate the facts.

McCorkindale said, in any case, failure to provide factual, real data is not only unethical, but erodes overall confidence in the profession and, as result, threatens to harm its effectiveness. It also compromises the effectiveness of an individual practitioner. “If you falsify information, they’re not going to trust you as a source,” said McCorkindale. “And that trust can be easily lost.”

For industry veteran Patrick Ford, Professional-in-Residence at the University of Florida, one disturbing trend is a “no holds barred, win at all costs,” approach. He pointed to situations where clients advocated for creating what amounted to deceptive tactics by, for example, displaying economic data in misleading ways. “We start from the premise that we must win and, in the process, declare all-out war,” he said. “And the first casualty is truth.” That attitude, according to Mark Stouse, CEO of Proof Analytics, is made even worse by a widespread focus on only short-term outcomes.

Another contributing factor, according to Stouse: the rise of content marketing. He attributed its growth to the confluence of two trends: 10 to 15 years ago, as mainstream media started to experience dire financial results, thanks to the rise of digital content, public relations professionals also began losing many valuable venues in which to place stories. The solution for many was content marketing, a new form of what was once called custom publishing, which leverages consumers’ tendency to trust what they view as reliable channels of information, as opposed to paid media. But that also has resulted in an increasingly blurred demarcation of what is real independent journalism and what is a form of publicity. “If there has been a black eye for PR, it has been the adoption of content marketing,” he said. “It has diluted and compromised the rest of the channels.”

What, then, can the industry do about the situation? “As a society and as public relations professionals, the first step in solving a problem is facing up to the fact that you have that problem,” said Ford.

For Ford, leadership plays a critical role. “We have to show people we do the right thing even if it cost us money,” he said. He cited a conversation that Harold Burson had with a client counseling against launching a new initiative. It would have been a lucrative assignment for the PR firm, but he felt the move would contradict the brand’s positioning, and was direct in his advice. The client decided not to pursue the initiative.

Part of that leadership also should involve pushing top management to include public relations executives in high level business decisions. “The PR director is the chief reputation officer and that title means you ensure that the reputation of your organization remains strong,” said West. “And if that person is not at the table, the company is going to suffer.”

In addition, public relations leaders can take steps to address the overall decline of civil discourse in the public sphere. That means encouraging a more reasoned debate and less shrill presentation of issues. “People end up shouting at each other or, more often, retreating into silos,” said James Campbell, distinguished professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. “For the polarization in our society to be rectified, we have to reach across the aisle.”

Many panelists also pointed to the need for greater diversity in the profession, including in top level positions. That means diversity in gender and ethnicity, as well as viewpoints. “If there are people in the group you disagree with, it means you have the chance to really listen to different opinions and understand where they’re coming from,” said McCorkindale. Achieving that goal would not only bring a variety of experiences and ideas to the table, but would act as a reality check on information accuracy.

More diversity would also help address the pernicious problem of unconscious bias—assumptions made by people they may not even be aware of. Ford pointed to a diversity training workshop he attended, during which facilitators presented participants with a selection of ethnically or gender-related insensitive comments and asked them to put a dot next to statements that were made directly to them or they overheard. When the results were presented, Ford realized he had placed almost no dots on any of the comments—and that he had been completely unaware, before that moment, of how prevalent such remarks were.

Training, in fact, was cited as another crucial element in the profession’s struggle against truth decay—education focused on raising media literacy and ethical standards, as well as diversity issues. Part of the effort would include setting more robust standards for ethics, implementing the recommendations of the Commission on Public Relations Education, case studies in managing ethical dilemmas, and, perhaps, strengthening the licensing and accreditation system for professionals. Such standards would be especially critical in high-stress times. “When you get into a crunch people make mistakes,” said Ford. “We need to train our people at every level of the organization how to make these judgements and what to do when you make them.”

Such education also should involve financial basics, according to Stouse. “Public relations people need to be businesspeople,” he said. Case in point: According to Stouse, one problem PR staff faced during the recent Wells Fargo scandal was their lack of business knowledge. “They were totally at the mercy of the information that was given to them.”

In summing up, moderator Lucas Held, director of communications at the Wallace Foundation, pointed to what may be the fundamental challenge facing public relations professionals: finding ways to be both persuasive and truthful. Referring to Aristotle’s writings about rhetoric, he said these two need not be in opposition: “Dialectics was seen as a means of identifying and elucidating the truth; persuasion was an approach to expressing that truth.”

Ultimately, panelists were optimistic about the role that public relations can play in tackling the crisis of truth decay—and the profession’s unique position as information influencers to step up to the plate. “Right now, we have a big opportunity to address this problem,” said Ford. “And PR people are especially well-positioned to do this.”