We Are No Longer in Charge

Virtually every innovation in the field of public relations over the last two decades has focused on one thing: engagement. We now want the voices of publics to feature prominently in our messaging. In fact, much of the writing about these innovations in the early 2000s argued that the role of public relations practice would be to facilitate co-creation of content with the audiences who consume it. Writers like Alex Wipperfürth in the 2006 book Brand Hijack goes so far as to claim that the perceptions and creations of consumers will define what our messages mean. This perspective is the natural evolution of PR research dating back to the ’90s that said the internet would create a future based entirely on dialogue and the messages constructed by publics. The inevitability of consumer control of public relations messages isn’t going away. That loss of control, however, raises a deeply concerning question, though. What happens when bad people co-opt the messages of good brands?

Hate Groups and Branding

This question is no longer hypothetical as hate groups are now regularly taking over PR messages and hijacking public perceptions. This phenomena, however, is not new. The origin of brands becoming important to hate groups can be traced back to the skinhead movement of the 1960s. Working class British youth distinguished themselves from the more upper class Mods by creating the well-known, distinct look that has since been associated with the racist skinheads. Utilization of certain brands ensures a uniform, group-specific look by which like-minded individuals could easily group together. Early examples of such brands commonly used by racist skinheads included Doc Martens, Londsdale, and Fred Perry, to just name a few. This look remained consistent until the late 1990s when Neo-Nazi crime waves began to plague Germany and other European nations. Neo-Nazis began to dress down and utilized a more mainstreamed fashion approach which allowed them to blend in and also gave individuals the chance to join hate movements without overt stigma. This “mainstream” hate group look contained hidden codes, symbols, and sometimes fashion brands, many of which are only obvious to in-group members.

Hatejacks

The internet has now allowed such brand co-optation to have an unprecedented level of visibility and reach. Our research on this subject led us to dub such events “hatejacks” which we comprehensively explore in our article “Hating in Plain Sight: The Hatejacking of Brands by Extremist Groups” published in the academic journal Public Relations Inquiry. These hatejacks now represent a danger that requires awareness from practitioners. As such, it’s important to consider some instances where excellent organizations have had their identity co-opted by bad actors.

Fred Perry

The brand Fred Perry focuses on sleek, high quality clothing reflecting the elegant appearance of the brand’s Wimbledon winning namesake. Unfortunately, the brand has gained traction with hate groups. The Proud Boys, specifically, utilize the gold-striped collar black polo shirt as a type of uniform for public group outings. Members of the group have appeared alongside other hate groups and have participated in extremist events such the “Unite The Right” rally in Charlottesville, which was co-organized by the Proud Boys and known extremist Jason Kessler. Group leaders have made racist, homophobic, and anti-Islamic statements, often donning very distinct black Fred Perry Polo shirts while making them. Through no fault of the brand, the public sharing of images of these groups has created an unwanted association for Fred Perry.

Tiki Torches

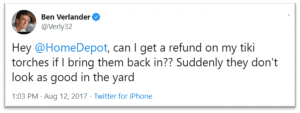

Tiki Torches have long been associated with a fun, playful take on tropical imagery that adds intrigue to backyard barbecues. The brand, however, was instantly associated with the extremists after marchers at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville carried Tiki Torches while chanting hateful invectives. An online search for “Charlottesville” and “Unite the Right” calls up hundreds of images of angry men carrying Tiki Torches. This unfortunate and unexpected association between the Tiki brand and hate was picked up almost immediately by traditional and social media. On Twitter, professional baseball player Ben Verlander posted:

Hey @HomeDepot, can I get a refund on my tiki torches if I bring them back in?? Suddenly they don’t look as good in the yard.

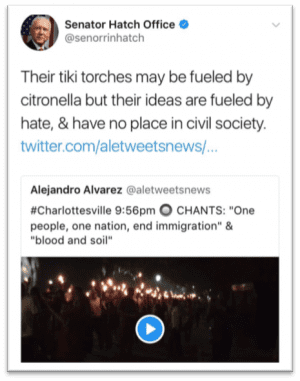

Similar sentiment was picked up by Senator Orin Hatch who posted:

Their tiki torches may be fueled by citronella but their ideas are fueled by hate, & have no place in civil society.

Wendy’s

Wendy’s has earned praise for their spontaneous, edgy, and frequently hilarious Twitter feed. That spontaneity and free-spiritedness was, unfortunately, co-opted in January of 2017. When a Twitter user asked Wendy’s a seemingly inconsequential question “got any memes?” Wendy’s social media team immediately replied by posting an image of Pepe the Frog wearing a red wig to approximate the brand’s signature logo.

Pepe the Frog is a non-political online comic figure that was co-opted by hate groups. The image of Pepe has since been noted as a symbol of concern by the Anti-Defamation League. Wendy’s was clearly unaware of this association. Pepe was likely just seen as a joke meme online and the wig looked funny. Unfortunately, members of hate groups celebrated the opportunity to claim supposed legitimization from an iconic American brand.

As news of this spread online and through the media, Wendy’s quickly deleted the tweet and stated “our community manager was unaware of the recent evolution of the Pepe meme’s meaning, and this tweet was promptly deleted.” Despite Wendy’s prompt action, media discussion of the tweet continued. An organization playfully using social media to brighten the lives of stakeholders had an innocuous message hijacked by hate.

Hateproofing Your Brand

These instances are not isolated and our research uncovered many, many more hatejacks of brands and public relations messages. So what can be done? There are several proactive and reactive strategies to think about.

Be proactive! Make your brand unattractive to the hateful.

Promoting diversity and supporting good causes is a sound strategy for any practitioner. The danger posed by hatejacks makes this even more important. By emphasizing an organization’s diversity and respect for difference, hate groups may think twice about claiming association with a group they disagree with. Additionally, should a hatejack happen, a company positively positioned as being tolerant and accepting will receive more sympathetic support in social and traditional media.

Respond quickly at the onset of a potential hatejack.

Crisis communication requires immediate response. This is especially true for a hatejack. A white supremacist group based in Michigan called the Detroit Right Wings publicly used the famous hockey logo of the Detroit Red Wings at an event. The Red Wings immediately issued a response stating “the Detroit Red Wings vehemently disagree with and are not associated in any way with the event taking place… we are exploring every possible legal action.” When two African American men were arrested for “loitering” at a Philadelphia Starbucks, it was precisely the sort of event that hate groups could latch onto. This was prevented by immediate action from CEO Kevin Johnson, a thorough investigation, and the chain temporarily closing all stores for employees to receive sensitivity and bias training. In both instances, quick and decisive action prevented any potential linkage between the brand and hate groups.

Do not directly engage.

There is a temptation to respond to hate groups in a hatejack. Our research suggests this may not always be productive. Responding directly to malicious posts from hate groups assumes good faith dialogue is possible. In this case, it is not. Even a well-reasoned reply to the hate group may be read or mischaracterized as validation. The audience for an organizational response should be the broader public; those who find the rhetoric of hate as offensive as you do.

Monitor, monitor, monitor.

Being aware of the conversation happening online is crucial for anyone doing PR in 2020. That awareness should also include a focus on the messaging of hate groups. Our study suggests polarizing events such as elections and large protests tend to be a catalyst for hatejacks. Knowing what hate groups are talking about, their symbology, and their public action allows for necessary risk assessment. Proactive and reactive responses to hatejacking require informed practitioners.

It is unfortunate that we live in a world where benevolent messages can by hijacked by people with evil intent. The internet has empowered the worst voices to successfully compete with the best intentions. Only through awareness and action can we ensure that our words aren’t unwittingly turned into weapons.

B